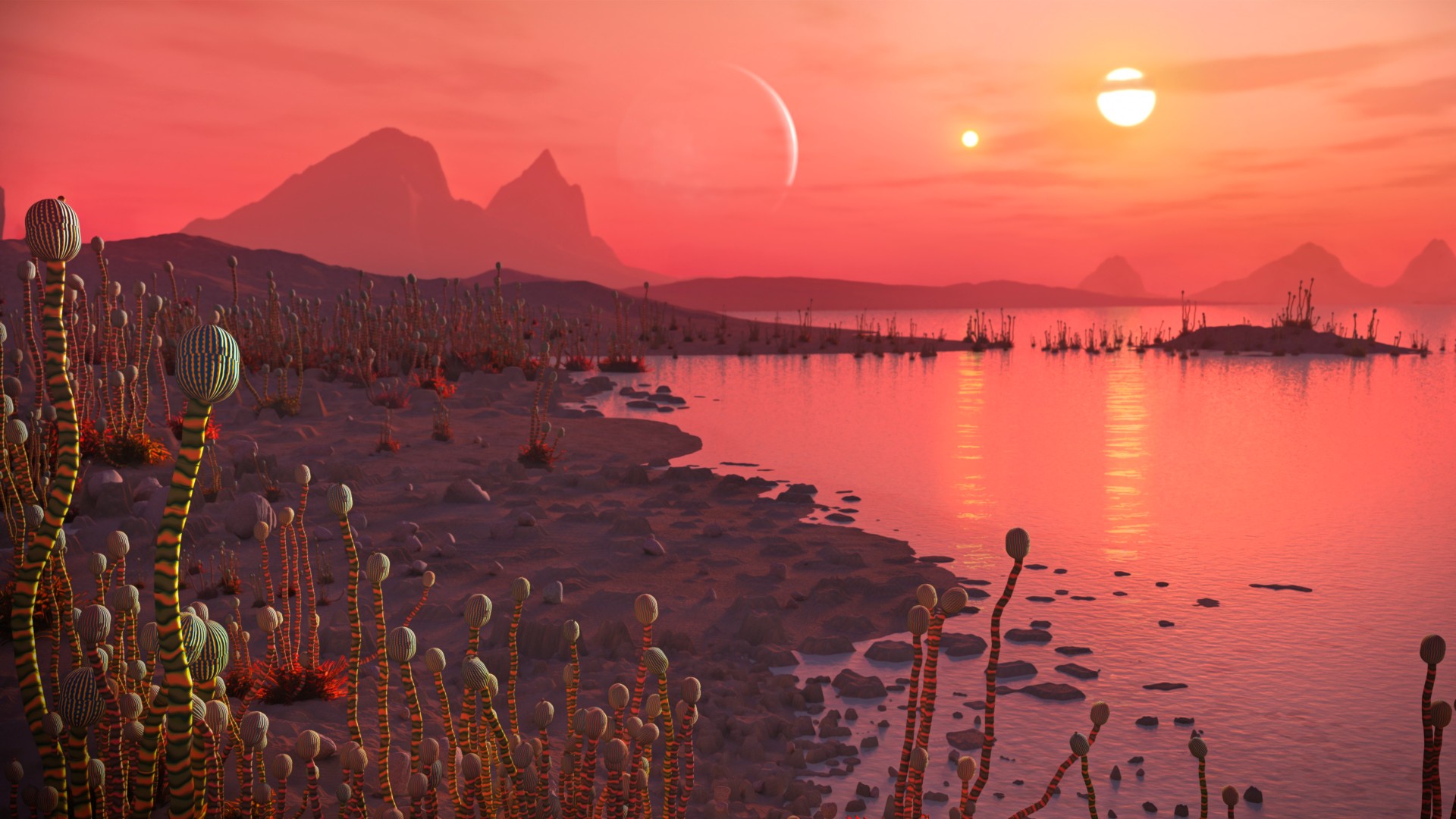

Alien life could be turning harsh planets into paradises — and astronomers want to find them

Early life made an inhospitable Earth more habitable, and aliens could be doing the same thing on their worlds, new research proposes.

Once life gains even the tiniest foothold on a planet, it may have the power to transform that world, forcing us to broaden our definition of "habitable," new research suggests.

We don't really know where life might arise. We have only one example of a life-hosting planet, Earth, which started to get interesting perhaps only a few hundred million years after it formed. We know that life on Earth requires a certain set of elements to perform its complex chain of energy production, that it needs liquid water as a solution, and that it can exist only in a relatively narrow range of atmospheric temperatures and pressures.

In our searches for life outside Earth, astronomers generally focus on an area called the habitable zone, a band of orbits around a star where liquid water can potentially exist on a planet's surface. If a planet is closer to the star, water will evaporate from the heat; if it's farther from the star, water will freeze into ice. Neither of those conditions are good for life as we know it.

But the habitable zone is only a rough guide, not a guarantee. Both Mars and Venus sit within the habitable zone of our sun, and those planets are not inhabited. On the other hand, the new research, published to the preprint server arXiv.org, suggests that our current definition of the habitable zone may be too narrow because it doesn't include how life influences a world.

A changing world

Earth would be completely different if it weren't for life. The classic example is the abundant quantities of oxygen in our planet's atmosphere. Oxygen is a very common element throughout the cosmos, and Earth was born with a lot of it. But most of that oxygen is bound up in the form of silicon dioxide — rocks. Gaseous oxygen can't survive in the atmosphere long, because ultraviolet radiation from the sun breaks it apart.

But the process of photosynthesis releases oxygen gas as a byproduct. In fact, early life produced so much oxygen that it almost poisoned itself in an incident known as the Great Oxidation Event. It took the evolution of oxygen-breathing creatures to put the ecosystem back in balance.

Either way, it would be incredibly difficult for Earth to maintain this much atmospheric oxygen if it weren't for the constant efforts of life.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This line of thinking can be extended to many other properties of Earth's atmosphere. Living creatures also emit large quantities of methane, a greenhouse gas that helps keep our planet warm. Vast forest canopies change the amount of sunlight reflected from the surface, also affecting the temperature of our world. Even the production of various gas byproducts from creatures large and small is capable of altering the air pressure of our planet's atmosphere.

The Gaian habitable zone

One way to look at all these changes is that once life gets started on a planet, it really doesn't want to go away. And so it goes about (unthinkingly, of course) altering the basic chemistry and physics of the planet to create a more suitable environment. This life-altered planet then becomes much more habitable than it was before.

This is certainly true of Earth. The earliest possible signs of life in the fossil record indicate that life may have arisen when our planet was still partially molten. It must have been a highly unfriendly place, but billions of years later, it's pretty great (unless we keep ruining everything with human-caused climate change).

The authors of the new paper imagined a world at the very edge of the habitable zone, either almost too cold or almost too hot. But if life managed to begin there, that life would have a chance of improving the planet's makeup, perhaps by raising or lowering the atmospheric pressure or temperature, or by creating niches underground where life could thrive.

Therefore, we must rethink the traditional definition of the habitable zone. The researchers propose a new one: the Gaian habitable zone (from Gaia, the Greek mythological personification of the Earth) . This zone would be wider than what we currently consider suitable for life, because life itself is capable of changing the boundaries of the suitable.

The researchers argue that we should employ these broader definitions of the habitable zone in selecting future targets for exploration. If the habitable zone is too narrow, we may miss signs of life, simply because we're looking in the wrong place. No matter what, when searching for extraterrestrial life, we must keep an open mind and be prepared for surprises. Life … finds a way.

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.