Greenland's Ice Sheet Was Growing. Now It's in a Terrifying Decline

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Greenland's ice sheet is melting six times faster than it was in the 1980s. And all that meltwater is directly raising sea levels.

That's all according to a new study, published yesterday (April 22) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, that carefully reconstructs the behavior of the ice sheet in the decades before modern measurement tools became available. Scientists already knew that there was a lot more ice on Greenland in the 1970s and 1980s. And they've had precise measurements of the increase in melting since the 1990s. Now they know just how dramatically things have changed in the last 46 years.

"When you look at several decades, it is best to sit back in your chair before looking at the results, because it is a bit scary to see how fast it is changing," University of California, Irvine, glaciologist Eric Rignot, a co-author of the study, said in a statement. [Image Gallery: Greenland's Melting Glaciers]

Greenland is just one island. But its ice sheet has the potential to transform the entire planet. The Greenland ice sheet has existed for 2.4 million years and is 2.1 miles (3.4 kilometers) thick at its deepest point. The whole thing weighs about half as much as Earth's whole atmosphere, or 6 quintillion — or 6 with 18 zeros after it — lbs. (2.7 quintillion kilograms). If it melted entirely, sea levels would rise by 24.3 feet (7.4 meters).

In the 21st century, scientists use laser measurements of the height of the ice, measurements of the ice sheet's total gravity and satellite photos to gauge changes in ice thickness. That's how they know that the sheet is melting four times faster now than it was in 2003, as Live Science previously reported.

To extend that record further into the past, the researchers divided Greenland into 260 "basins" of ice, which they studied individually using a combination of direct measurements of ice changes in satellite photos and sophisticated computer models of ice behavior. They found that between 1972 and 1980, Greenland actually gained roughly 100 trillion lbs. (47 trillion kg) of ice per year. The real mass loss, they found, started in the 1980s. Between 1980 and 1990, the island lost in the ballpark of 112 trillion lbs. (51 trillion kg) of ice per year. Between 1990 and 2000, it lost about 90 trillion lbs. (41 trillion kg) per year.

Then, in the 2000s, things dramatically accelerated.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Between 2000 and 2010, Greenland lost about 412 trillion lbs. (187 trillion kg) of ice per year. Between 2010 and 2018, the ice sheet lost roughly 631 trillion lbs. (286 trillion kilograms) of ice per year.

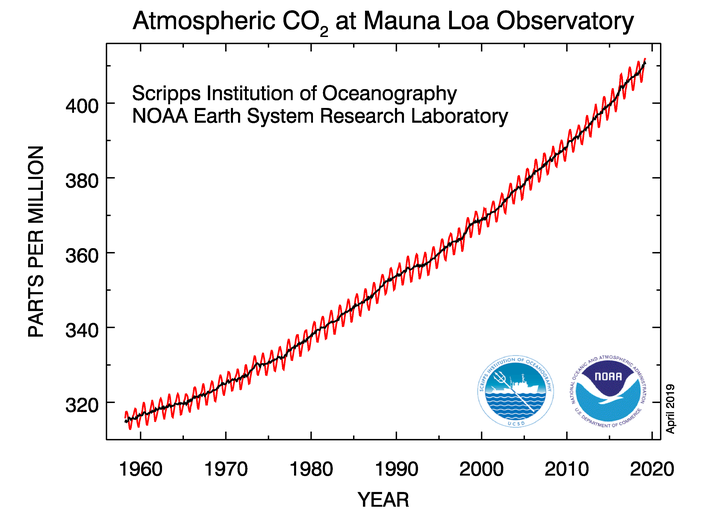

Those numbers make concrete what researchers and inhabitants of Greenland already knew: that the island is changing and its ancient glaciers are receding at an alarming rate. The dramatic uptick in ice loss in the last two decades coincides with a similar surge in atmospheric greenhouse gases and warming. As Live Science reported earlier this year, nine of the 10 warmest winters on record have happened since 2005.

What does this all mean for the future of the ice sheet, as well as global sea levels? As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded, that will depend primarily on what humans do next.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus