Flat-Earthers' Cruise Will Sail to Antarctica 'Ice Wall' at the Planet's Edge. Right.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Organizers of an annual conference that brings together people who believe that the Earth is flat are planning a cruise to the purported edge of the planet. They're looking for the ice wall that holds back the oceans.

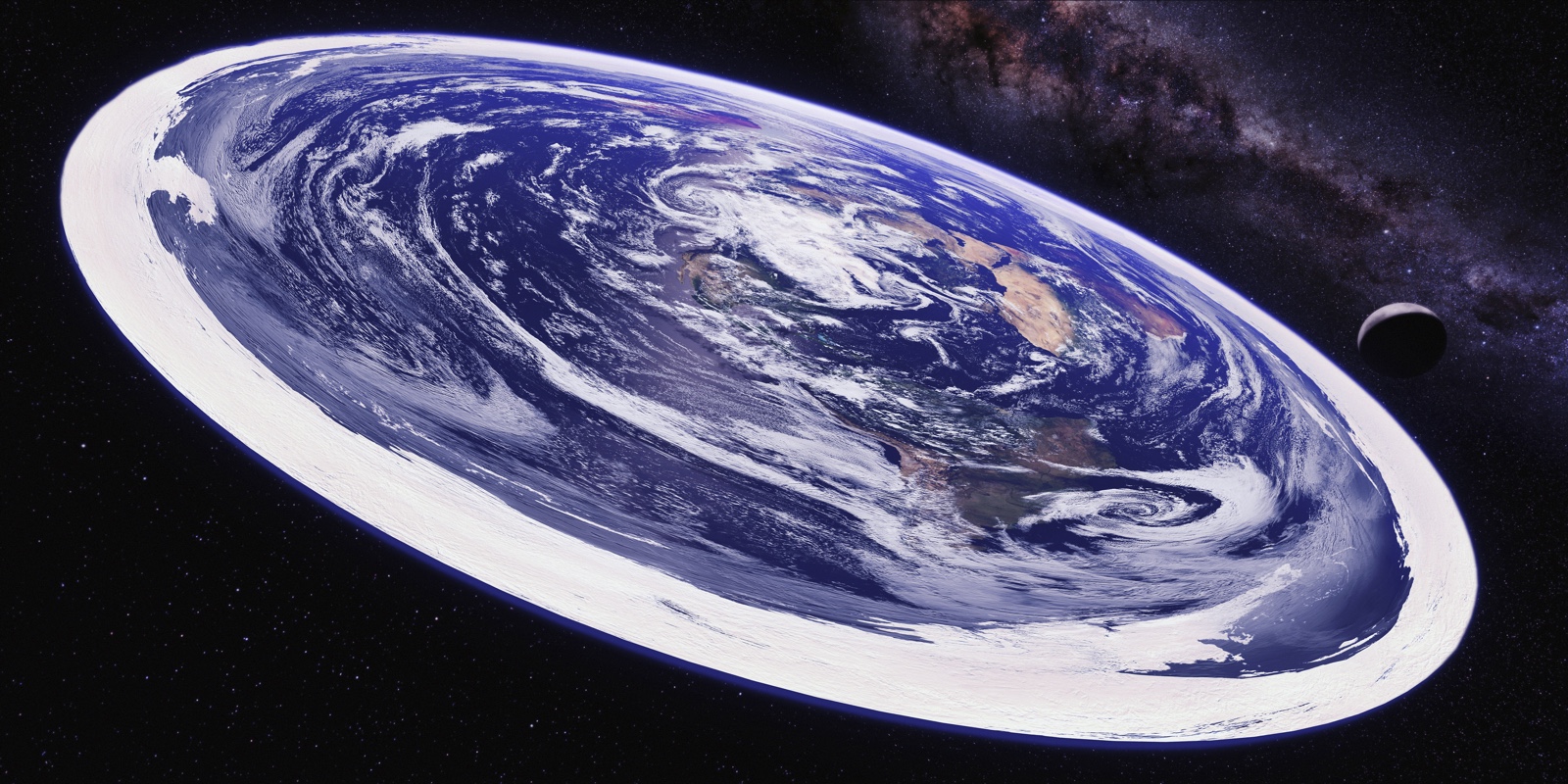

The journey will take place in 2020, the Flat Earth International Conference (FEIC) recently announced on its website. The goal? To test so-called flat-Earthers' assertion that Earth is a flattened disk surrounded at its edge by a towering wall of ice.

Details about the event, including the dates, are forthcoming, according to the FEIC, which calls the cruise "the biggest, boldest adventure yet." However, it's worth noting that nautical maps and navigation technologies such as global positioning systems (GPS) work as they do because the Earth is … a globe. [7 Ways to Prove the Earth Is Round]

Believers in a flat Earth argue that images showing a curved horizon are fake and that photos of a round Earth from space are part of a vast conspiracy perpetrated by NASA and other space agencies to hide Earth's flatness. These and other flat-Earth assertions appear on the website of the Flat Earth Society (FES), allegedly the world's oldest official flat Earth organization, dating to the early 1800s.

However, the ancient Greeks demonstrated that Earth was a sphere more than 2,000 years ago, and the gravity that keeps everything on the planet from flying off into space could exist only on a spherical world.

But in diagrams shared on the FES website, the planet appears as a pancake-like disk with the North Pole smack in the center and an edge "surrounded on all sides by an ice wall that holds the oceans back." This ice wall — thought by some flat-Earthers to be Antarctica — is the destination of the promised FEIC cruise.

There's just one catch: Navigational charts and systems that guide cruise ships and other vessels around Earth's oceans are all based on the principle of a round Earth, Henk Keijer, a former cruise ship captain with 23 years of experience, told The Guardian.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

GPS relies on a network of dozens of satellites orbiting thousands of miles above Earth; signals from the satellites beam down to the receiver inside of a GPS device, and at least three satellites are required to pinpoint a precise position because of Earth's curvature, Keijer explained.

"Had the Earth been flat, a total of three satellites would have been enough to provide this information to everyone on Earth," Keijer said. "But it is not enough, because the Earth is round."

Whether or not the FEIC cruise will rely on GPS or deploy an entirely new flat-Earth-based navigation system for finding the end of the world, remains to be seen.

- Religion and Science: 6 Visions of Earth's Core

- 101 Images of a Round Earth Taken from Space

- 8 Times Flat-Earthers Tried to Challenge Science (and Failed) in 2017

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus