8 Times Flat-Earthers Tried to Challenge Science (and Failed) in 2017

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

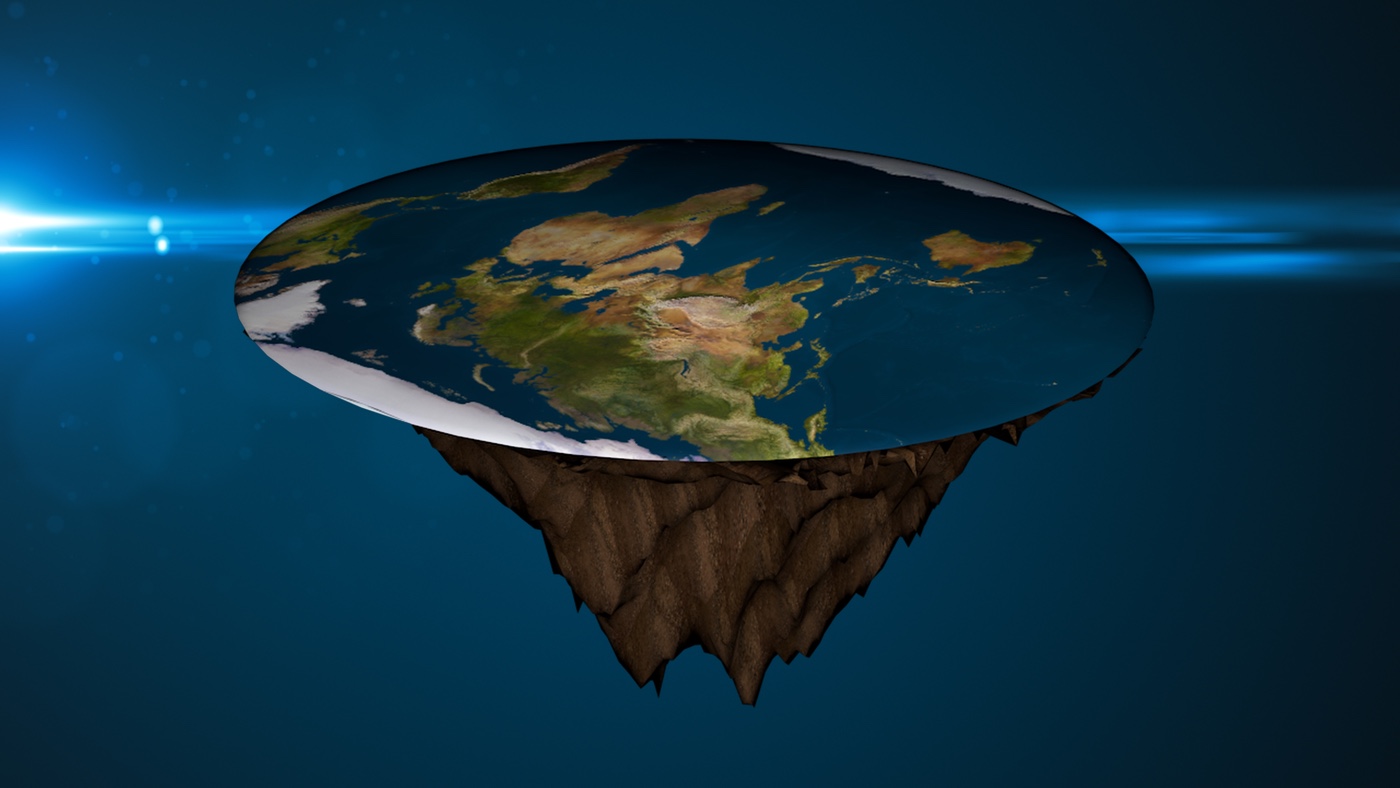

In the stew of false information and conspiracy theories that swirls online, perhaps no idea is as flummoxing as the belief in a flat Earth. Flat-earthers believe that the Earth is a flat disc ringed by an ice wall. All those elegant models of a round Earth that perfectly explain seasons, eclipses, sunrises and sunsets? Lies and cover-ups, they say. Pictures of the round Earth from space? Government conspiracies. The fact that you can see ships disappearing hull-first over the curve of the horizon with your own eyes? Well, flat-earthers claim to see something different.

It's been a big publicity year for flat-Earthers, who have gained celebrity backers, promised death-defying stunts in the name of their theory and held their first conference. Here are eight times the conspiracy theorists have gotten their names out there in 2017.

1. Shaq attacks Earth's roundness

Basketball player Shaquille O'Neal was roundly mocked online when he announced on his podcast in March that Earth is "flat to me." He went on: "I do not go up and down at a 360-degree angle, and all that stuff about gravity. Have you looked outside Atlanta lately and seen all these buildings? You mean to tell me that China is under us? China is under us? It's not. The world is flat."

Article continues belowA few days later, though, Shaq announced that he was just messing with everyone: "I'm joking, you idiots," he clarified. [5 Scientific Rebuttals of Shaq's Flat-Earth Claims]

But people who think the world is flat aren't necessarily primed to believe their ears when they hear a beloved celebrity saying he was just making a joke of their theories. A quick stroll through the Flat Earth Society forums suggests that some true believers now think Shaq was simply pressured into retracting his statements and that he's on their side.

2. Rapper B.o.B crowdfunds a satellite

The rapper B.o.B, also known as Bobby Ray Simmons Jr., is famous for having gotten into a Twitter fight with physicist Neil deGrasse Tyson over whether the Earth is round. B.o.B raised his profile further this year with an attempt to crowdfund his own rocket launch to carry a camera into space to look for the curvature of the Earth. Flat-Earthers, of course, don't believe in the Earth's curvature (which, for the record, becomes visible to the human eye at about 35,000 feet (11,000 meters) elevation, but only given at least a 60-degree field of view, according to a 2008 paper, making it hard to detect from a typical passenger airliner window). Two months after the fundraiser was posted, B.o.B had reached $6,883 of his $1 million goal, the first thousand of which he donated himself, according to his GoFundMe page.

3. Kyrie Irving gets on board

What is it with NBA players? Kyrie Irving of the Celtics has had a complex relationship with the flat Earth in 2017. As SB Nation breaks it down, the point guard declared the Earth flat on a podcast in February, and then returned to the same podcast in March to say he was just trying to start a conversation. In September, he was asked by CBS Boston what he really believed and said his original statements were just an "exploration tactic" and that people should do their own research. In October, he again floated the notion that the question of whether Earth is round is up for debate, saying he didn't know whether pictures of Earth from space were real.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

4. Solar eclipse fuels conspiracy theories

Eclipses are moments when it becomes really possible to look up and remember that you live on a spinning ball. Well, unless you're a flat-Earther. Then, they're proof, duh, that the Earth is flat.

Flat-Earthers used the Aug. 21 total solar eclipse that crossed the contiguous United States as "evidence" of their beliefs. According to Forbes, they argued that the west-to-east eclipse path was evidence of something fishy, because the sun moves across the sky from east to west, right? (Actually, the moon orbits Earth from west to east, so the moon's shadow follows the path of the moon.) Flat-Earthers also argued, using flashlights and coins, that the moon's shadow should have been bigger than the moon itself. The problem with this argument is that the sun is an extremely distant, diffuse source of light, not a nearby point source, so the flashlight analogy doesn't fit. Instead, the moon is like a tiny speck against the backdrop of the sun's massive light.

5. Homemade rocket launch fizzles

In November, flat-Earther "Mad" Mike Hughes announced plans to launch himself 1,800 feet (550 m) above the Mojave Desert in a steam-powered rocket he made out of salvaged parts. His plan was to attempt to photograph the lack of curvature of the horizon to "prove" the Earth's flatness. The curvature of the horizon is subtle enough as to not be visible until at least 35,000 feet, so it's unclear exactly what Hughes hoped to prove. Nevertheless, his homemade rocket cost a reported $20,000, making it quite a deal compared with B.o.B's estimated $1 million rocket-launch scheme.

Unfortunately for Hughes, his launch was to take place on public land, and the Bureau of Land Management shut him down at the last minute.

6. Flat-Earthers hold a conference

The internet has undoubtedly expanded flat-Earth believers' reach. The Economist recently reported that, based on Google Trends data, interest in "flat earth" as a search term has risen significantly over the past two years. Flat-Earthers are now meeting in person, too. The first-ever Flat Earth International Conference was held this year in Raleigh, North Carolina. It was hosted by Kryptoz media and the Creation Cosmology Institute, both of which use religious overtones in their flat-Earth philosophizing. The organizer of the conference told Live Science that about 500 people attended.

7. Earth is flat; Mars is round

As founder of SpaceX, Elon Musk knows a little something about the challenges of launching rockets off an obloid sphere into space. So when he tweeted in November, "Why is there no Flat Mars Society?!" he probably didn't expect an actual answer.

Well, he didn't really get one, either. But he did get a response, straight from the Flat Earth Society itself (@FlatEarthOrg): "Hi Elon, thanks for the question. Unlike the Earth, Mars has been observed to be round. We hope you have a fantastic day!"

Why does the Flat Earth Society believe in direct observations of Mars' roundness but not Earth's? Who knows. But flat-Earthers tend to have complicated, often contradictory, explanations of how astronomy works in the absence of a round Earth. The Flat Earth Society pushes a view in which the sun rotates over the top of the disk of the Earth like a baby's mobile at a much closer distance than the 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) away that it actually is. The other planets — which, in this theory, are also much smaller and closer than they are in reality — orbit the sun, the Flat Earth Society believes.

8. Another athlete asks questions

Whatever is in the water at the NBA is apparently affecting the cricket world, too. Former English cricketer Freddie Flintoff recently hit the tabloid circuit with his opinion that the Earth is flat, or possibly turnip-shaped (OK, sure). Flintoff discussed his belief on his BBC Radio 5 podcast in November, asking why the water in the ocean doesn't wobble if Earth is hurtling through space. (It's because Earth's rotational speed is basically constant, forgiving an imperceptible slowdown of about 2 milliseconds per century. The oceans move with this constant spin just as a passenger in a car traveling down the highway moves at the same speed as the car. Rotation does cause Earth to bulge at the equator, though, which is why the planet is an obloid shape rather than a perfect sphere.) Flintoff said he got his ideas from listening to a flat-Earth podcast.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus