Bonanza of Bizarre Cambrian Fossils Reveals Some of the Earliest Animals on Earth

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

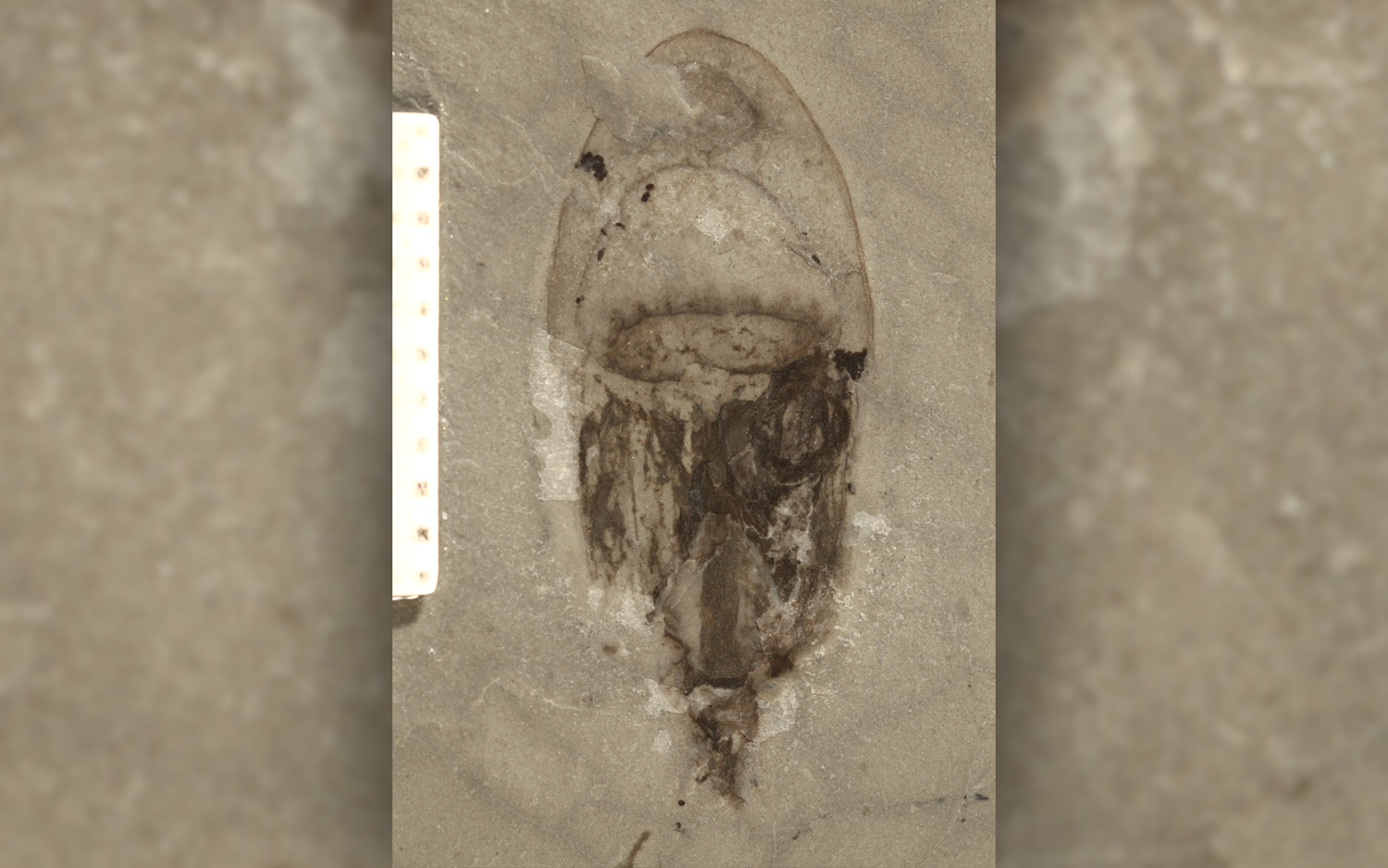

A newfound fossil site in China is teeming with bizarre, primitive species that have never before been found any place on Earth. The bounty of creatures includes a spiny, segmented animal known as a mud dragon, and several jellyfish with preserved tentacles.

Paleontologists discovered this treasure trove of fossils, which are incredibly well-preserved, along the banks of the Danshui River in southern China. The dozens upon dozens of creatures date to the Cambrian Period (490 million to 530 million years ago), when Earth's animal diversity was booming at an unprecedented pace.

Scientists collected hundreds of specimens and identified fossils of 101 animals. Of those, more than half are new species that have yet to be described, the researchers reported in a new study. [Image Gallery: Cambrian Creatures: Primitive Sea Life]

"It is a huge surprise to find a new deposit of such incredible richness and with such a large proportion of species that are completely new to science," study co-author Robert Gaines, a professor in the Geology Department at Pomona College in California, told Live Science in an email.

Researchers in China discovered the site while exploring early Cambrian rocks nearby. During their lunch break by the river, the scientists noticed "a striking pattern of alternating gray and black stripes" in the rocks of the river bank. This type of sediment pattern indicates areas where ancient mudflows once surged — flows that may have buried and preserved ancient organisms, Gaines explained.

The scientists started chipping away at the rock, and sure enough, they soon detected the first of the site's exceptional fossil remains, now known collectively as the Qingjiang biota, they wrote in the study.

All told, the team uncovered fossils of more than 50 species unknown to science. Many of the fossils — bell-shaped jellyfish, spiky worms, armored arthropods and more — retain an astonishing level of detail in their preserved soft tissues, such as gills, digestive systems and even eyes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Qingjiang is a new window on a different type of early Cambrian ecosystem," Gaines said.

As in other rich fossil deposits of well-preserved Cambrian life — the Burgess Shale deposits in Canada and the Chengjiang deposits in China's Yunnan Province — the Qingjiang animals had been quickly swallowed by mudflows and then buried in fine-grain soils, Gaines said. As sediment "cemented" around the tiny bodies, it locked out microbes and halted the process of decay.

This preserved "exquisite primary organic remains of creatures like jellyfish and worms that usually leave no fossil record," he said.

In fact, jellyfish and sea anemones, which are among the earliest known animals, are far more numerous in the Qingjiang biota than in the Burgess Shale or Chengjiang sites, the researchers reported.

What's more, the Qingjiang fossils' condition is substantially better than that of fossils at the other Cambrian sites. At Burgess Shale, the formation of the Rocky Mountains heated and compressed the fossils; though anatomical details remained, the fossils were reshaped from their original forms, according to Gaines. And in Chengjiang, groundwater that flowed over the fossil deposits over millions of years also carried away some of the detail of their original shapes.

"The Qingjiang fossils, however, are pristine, and appear much as they would have after they were fossilized in the Cambrian period," Gaines said.

The findings were published online today (March 21) in the journal Science.

- These Bizarre Sea Monsters Once Ruled the Ocean

- Photos: 508-Million-Year-Old Bristly Worm Looked Like a Kitchen Brush

- Photos: 'Naked' Ancient Worm Hunted with Spiny Arms

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus