Earth's Magnetic Field Booms Like a Drum, But No One Can Hear It

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

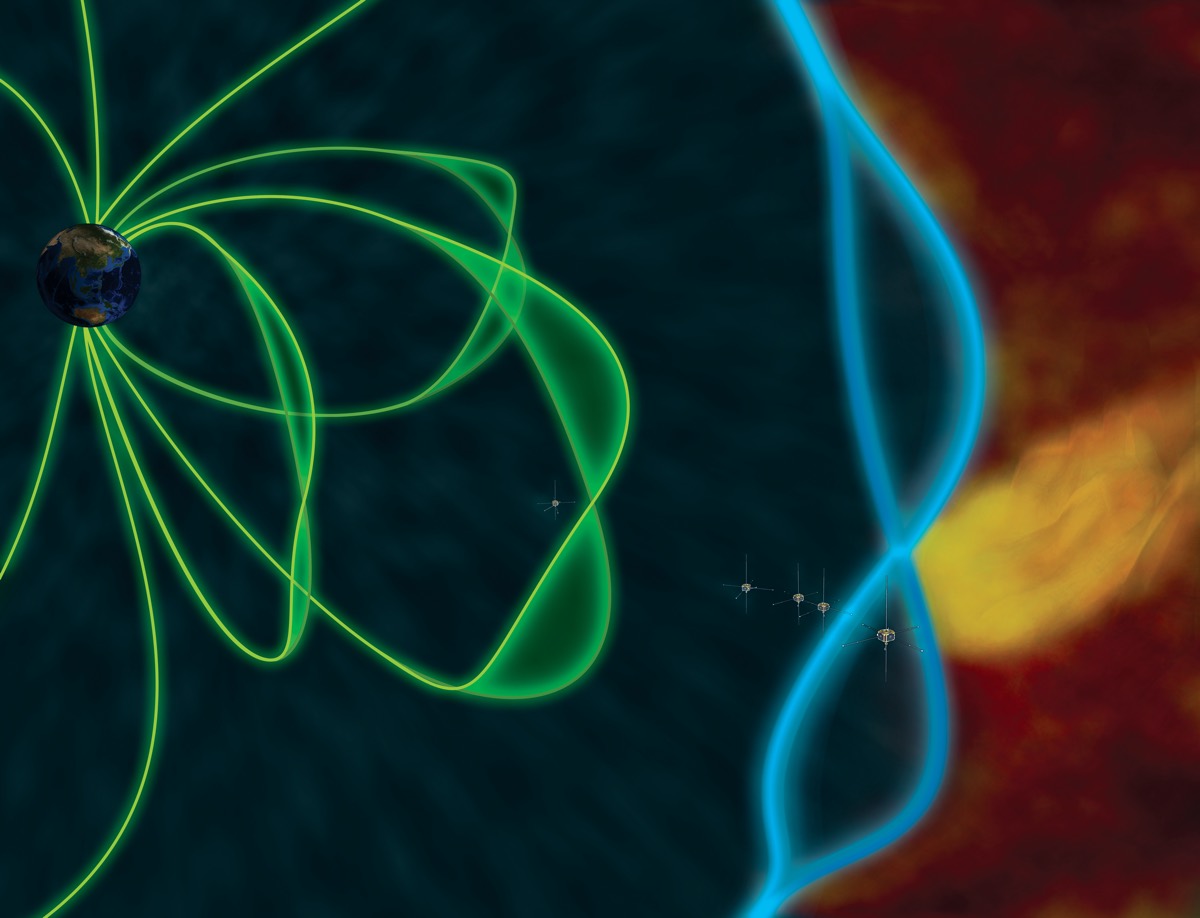

Every time an impulse strikes the shield's outer boundary — a region known as the magnetopause — jolts ripple through its surface and then are reflected back once they reach the magnetic poles, just like the face of a drum ripples as a percussionist beats it.

And (drum roll) this is the first time since researchers proposed the magnetopause-is-like-a-drum idea 45 years ago that technology has recorded the phenomenon directly, the researchers said. [What's That Noise? 11 Strange and Mysterious Sounds on Earth and Beyond]

The dayside magnetosphere, the side of the magnetic field directly between the Earth and the sun, is a vast place. It usually extends some 10 times the radius of the Earth toward the sun, or about 41,000 miles (66,000 kilometers), said study lead researcher Martin Archer, a space plasma physicist at Queen Mary University of London.

Movements in the magnetopause can impact the flow of energy within Earth's space environment, Archer noted. For instance, the magnetopause can be impacted by solar wind, as well as charged particles in the form of plasma that blow off the sun. These interactions with the magnetopause, in turn, have the potential to damage technology, including power grids and GPS devices.

Although physicists had proposed that blasts from space could vibrate the magnetopause like a drum, they had never seen it in action. Archer knew this would be a challenging phenomenon to capture; one would need several satellites in just the right places at the right time (that is, just as the magnetopause was blasted with a strong impulse). These satellites, it was hoped, would not only capture the vibrations but also rule out other factors that might have caused or contributed to the drum-like waves.

But Archer and his team were undeterred, and studied the theory of these drum-like oscillations, taking into account certain complexities that were omitted from the original theory, Archer told Live Science. "This involved combining more realistic models of the entire dayside magnetosphere, as well as running global computer simulations of the magnetosphere's response to sharp impulses."

These models and simulations "gave us testable predictions to search for in satellite observations," he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Next, the scientists compiled "a list of criteria that would be required to give unambiguous evidence of this drum," Archer said. These criteria were strict, and required the presence of at least four satellites in a row near the magnetosphere boundary. Only then could the researchers gather data on the driving impulse, the motion of the boundary and the signature sounds within the magnetosphere, he said.

Amazingly, the everything fell into place for the researchers. NASA's Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms (THEMIS) mission has five identical probes that were studying the aurora polaris, or the polar lights. These spacecraft were able to tick off every box that Archer and his team needed to confirm that the magnetosphere vibrated like a drum, he said. [Infographic: Earth's Atmosphere Top to Bottom]

"We found the first direct and unambiguous observational evidence that the magnetopause vibrates in a standing wave pattern, like a drum, when hit by a strong impulse," Archer said. "Given the 45 years since the initial theory, it had been suggested that they simply might not occur, but we've shown they are possible."

Archer describes the finding in more detail in a video he created.

The finding was music to Archer's ears.

"Earth's magnetic field is a gigantic musical instrument whose symphony affects us greatly through space weather," he said. "We've known analogs to wind and string instruments occur within it for decades, but now we can add some percussion into the mix, too."

However, it's basically impossible to hear these vibrations in space. "The frequencies we detected — [between] 1.8 and 3.3 millihertz — are over 10,000 times too low in pitch to be audible to the human ear," Archer said.

Moreover, "there are so few particles in space, that the pressures associated with the oscillations wouldn't be strong enough to move an eardrum," he noted. In order to hear the data, he and his team had to "manipulate the data from the sensitive instruments onboard the THEMIS probes to convert the signals into something audible to us."

The study was published online today (Feb. 12) in the journal Nature Communications.

Editor's Note: The story was corrected to change megahertz to millihertz. A millihertz is a thousand times smaller than a Hertz, which is why the frequencies from the magnetopause are too low in pitch for the human ear to hear.

- Image Gallery: Amazing Auroras

- Happy Birthday, Hubble! 10 Epic Photos from the Iconic Space Telescope

- Photos: The 2017 Great American Solar Eclipse

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus