7,000-Year-Old Massacre: 9 Neolithic Outsiders Murdered with Blows to the Head

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 7,000 years ago, the bodies of nine brutally murdered people were dumped into a mass grave on the edge of an ancient farming settlement. While their identities will never be known, one thing is certain: These nine individuals were interlopers — possibly failed raiders or POWs — who met violent ends, a new study finds.

These people aren't the only early Neolithic victims whose lives ended in violence. But several factors set this newfound burial — found during a construction project in Halberstadt, Germany, in 2013 — apart from other mass graves dating to the same period, the researchers said.

For starters, these victims weren't local, but "outsiders with currently unknown origins," said study lead researcher Christian Meyer, an archeologist who researched the burial while working at the State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology of Saxony-Anhalt, in Germany. [25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

The "outsider" discovery was made thanks to an anaylsis of certain isotopes (a variation of an element that has a different number of neutrons in its nucleus) in people's bones and teeth that are determined by their diets. The analysis revealed that the victims in the mass grave had different isotopes in their remains compared with other people buried in the settlement, the researchers said.

In addition, the newfound grave contained only adults — eight men and one woman — but no children, which is unusual for Neolithic mass graves, Meyer said. For instance, another early Neolithic mass grave in Germany, known as Schöneck-Kilianstädten, had 26 victims, which included 13 children and 11 men and two women, Live Science previously reported.

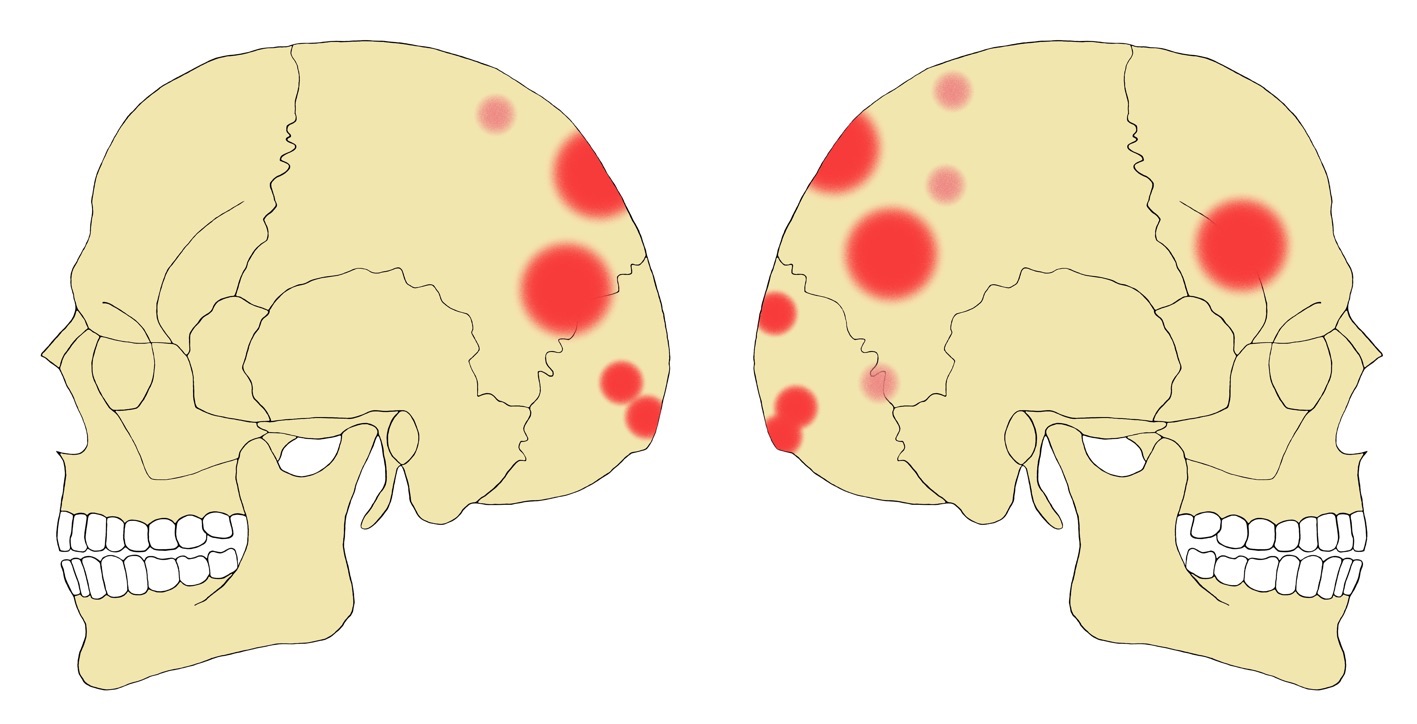

Moreover, these young adults' injuries clustered at the back of the head, meaning the victims were likely hit with "blunt force" from behind, Meyer said.

"At other sites, where [other] chaotic massacres occurred, injuries are usually spread out over all areas of the skulls," Meyer told Live Science in an email. "Some of the injuries [at Halberstadt] also appear quite similar in size and shape, so overall one can assume a rather controlled application of lethal violence."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

He noted that during the early Neolithic, the Halberstadt settlement belonged to the Linearbandkeramik (LBK), the first farming culture in Central Europe that planted crops and raised livestock. The settlement also contained traces of six LBK longhouses and regular burials, most of which hold just one person and LBK artifacts.

"The mass grave differs greatly from these regular, individual graves, as the bodies were just dumped into the mass grave pit and were not carefully arranged." Meyer said.

What happened?

Based on the evidence, it appears that "a group of non-local younger men [were] killed in a controlled manner" like executed prisoners, Meyer said.

At least two scenarios are possible: Either the victims were captured nearby (possibly as part of a failed raiding party) or they were brought in from farther away as POWs, Meyer said.

"We don't really know the answer," he said. But given that there's no evidence that LBK men were captured as POWs, it seems more likely that the victims were apprehended during a raid or farther away from the settlement, Meyer said.

"Likely they were LBK farmers as well, but from another area," he said. [In Images: Deformed Skulls and Stone Age Tombs from France]

The massacre suggests that this settlement had heightened conflict and social pressures that led to this violence, said Meaghan Dyer, a doctoral candidate in the School of History, Classics and Archaeology at the University of Edinburgh who was not involved in the study.

"This site provides a clearly differing pattern to other known massacres, representing a previously unknown practice of large-scale, male-targeted execution," Dyer told Live Science. "[It sheds] new light on interpersonal violence during a very key point in human prehistory."

The study was published online June 25 in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus