T. Rex Couldn't Stick Out Its Tongue

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

T. rex may have been a highly successful predator, but it would have been terrible at licking stamps, lollipops or popsicles, thanks to a tongue that was likely fixed to the bottom of its mouth.

A new study calls into question artists’ renditions of T. rex and other dinosaurs that show them with their tongues protruding from gaping jaws — a pose that is commonly seen in modern lizards. But even though lizards are tops at tongue waving, dinosaurs probably couldn't stick out their tongues, researchers recently discovered.

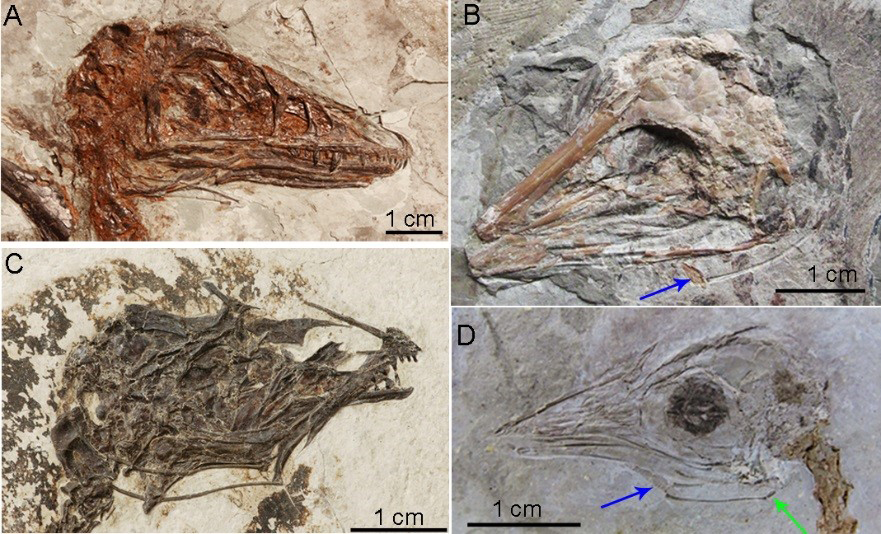

Soft tissue is rarely preserved in the fossil record, so scientists turned their attention to a structure called the hyoid — a group of bones that supports and anchors the tongue. They looked at hyoids in dinosaurs and in their closest living relatives, birds and crocodilians, to see if they could lick the problem of tongue-wagging capabilities in extinct dinosaurs.

Based on similarities they found between dinosaur and crocodilian hyoid bones, the researchers found that dinosaurs' tongues were probably like those of alligators and crocodiles — firmly attached to the floor of their mouths. [Image Gallery: The Life of T. Rex]

"This is an aspect of dinosaur anatomy that people probably don't think about, but it's a key part of any organism's lifestyle," study co-author Julia Clarke, a professor of vertebrate paleontology with the Jackson School of Geosciences at The University of Texas at Austin, told Live Science.

Portrayals of dinosaurs with lizard-like tongues hearken to early interpretations of the beasts as oversized lizards. This misconception persists in popular representations of dinosaurs today, even though it has been long-established that dinosaurs' closest living relatives are birds and crocodilians, Clarke explained.

Modern bird tongues are exceptionally diverse and can be highly mobile, thanks to complex hyoids that include multiple structures that may extend along the midline to the tongue's tip. Hummingbird tongues, for example, are flexible micropumps that are so long that they spool around the bird's skull when retracted, like a tape measure.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, most extinct dinosaurs have hyoid structures that are more like those of crocodilians — a simple pair of short rods. In alligators, crocodiles and their relatives, muscle and connective tissue fix the animals' tongues along the entire length, from base to tip. Hyoid similarities between dinosaurs and crocodilians suggest that their tongues resembled each others' as well, so dinosaurs were probably not capable of the tongue-stretching feats exhibited by birds, Clarke said.

The scientists did find similarities between birds' hyoids and those in an unexpected group: pterosaurs. Like birds, pterosaurs can fly. But the group represents a different archosaur lineage than dinosaurs, and they are not close relatives.

What could explain the resemblance between hyoid structures in birds and pterosaurs? One possibility is that the two groups separately evolved more complex and mobile tongues as they took to the skies, to better manage a new type of diet that wasn't available to ground dwellers, the researchers wrote in the study, published online today (June 20) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Meanwhile, the presumably less-mobile tongues of dinosaurs could have served them well in feeding strategies like those used by crocodilians — a "bite-and-swallow" approach — where tongues play a less active role and don't manipulate the food much after it's in their mouths, Clarke told Live Science.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus