This 'Hawk Mummy' Was Actually Human

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

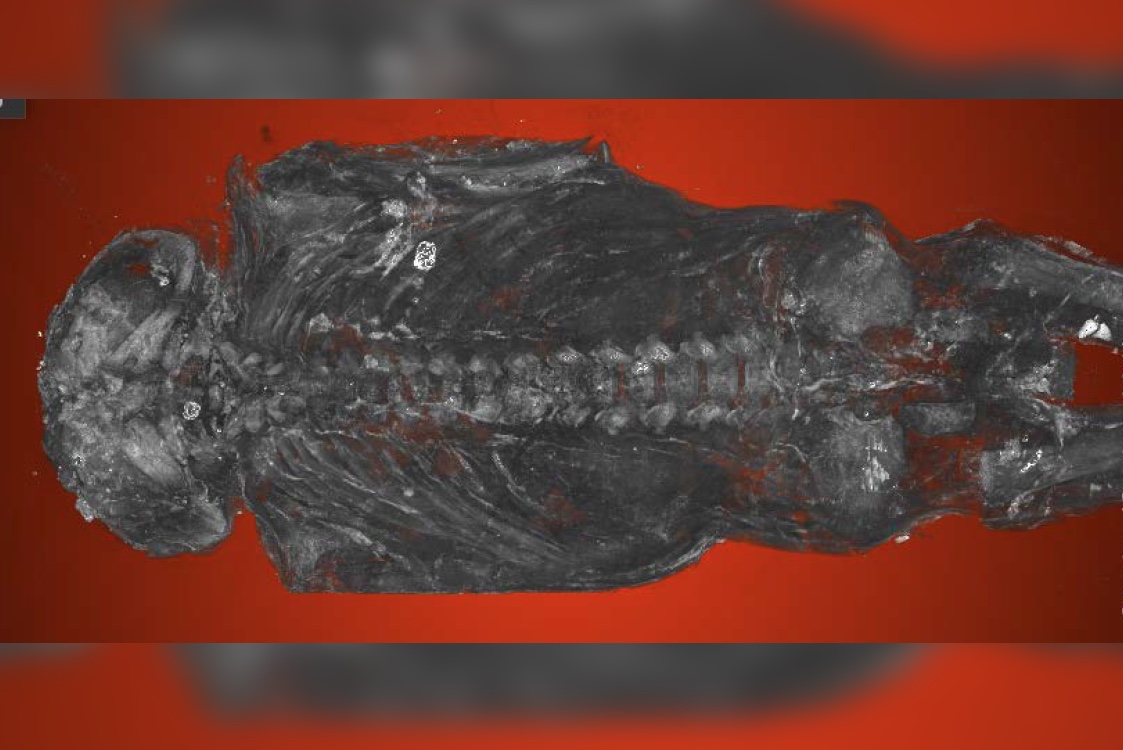

The 2,100-year-old mummified remains of what was thought to be a "hawk mummy" actually belong to a stillborn boy who suffered from anencephaly, a rare condition in which part of the brain and skull fails to develop.

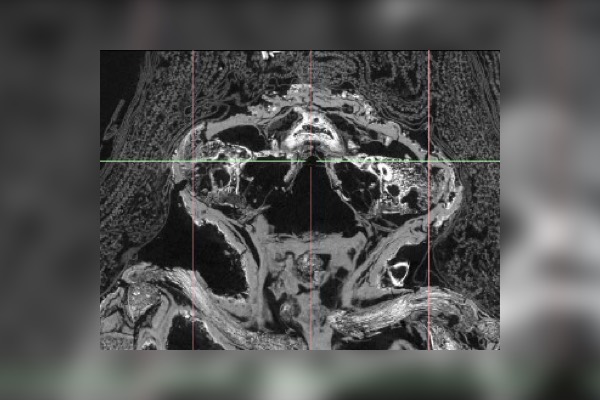

"The whole top part of his skull isn't formed," Andrew Nelson, a bioarchaeologist and professor of anthropology at the University of Western Ontario, said in a statement. "The arches of the vertebrae of his spine haven't closed. His earbones are at the back of his head" Nelson said.

The mummy is one of only two confirmed mummies from Egypt known to have anencephaly. [Photos: The Amazing Mummies of Peru and Egypt]

The mummy was donated to the Maidstone Museum in the United Kingdom in 1925 by a local physician and has been on display at times. "It was believed to be a votive hawk mummy because of the cartonnage" that the ancient Egyptian put the mummy is in, Nelson told Live Science. Cartonnage consists of layers of linen or papyrus covered with decorated plaster. A picture of the cartonnage shows that the top part looks a bit like a hawk.

Nelson led a team of scientists who examined the mummy using micro-CT scanning, a technique that allowed them to get high-resolution images of the tiny fetus mummy without opening the cartonnage.

They found that the mummy would have been stillborn at a gestational age of 23 to 28 weeks. "It would have been a tragic moment for the family to lose their infant and to give birth to a very strange-looking fetus, not a normal-looking fetus at all," Nelson said in a statement. "So this was a very special individual."

The fetus seems to have been carefully mummified, the researchers said. In addition, an image on the cartonnage shows Osiris, the Egyptian god of the underworld, lying on a coffin frame called a bier, with the goddesses Isis and Nephthys standing over him. A "ba-bird" (a mythical bird with a human head) is shown flying over Osiris in the scene, and above that is an Udjat eye, which is "a symbol of protection and good health," Nelson said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A mummy with power?

The mummy may have had a "power" of sorts at the time because it was a fetus, Nelson said. "The suggestion that the fetus would have had agency or power comes from a legal petition dating to the Roman times, where a farmer complains that someone who was stealing his grain used a fetus to stop him from stopping the theft," Nelson said. In the story, the thief throws a fetus at the farmer, and "the power of the fetus was such that the farmer and several village elders were frozen into inaction," he added.

Nobody knows where or how the mummy was buried, or if anyone tried to take advantage of any believed powers associated with this mummy, Nelson said.

The only other confirmed case of an Egyptian mummy with anencephaly was described by the French zoologist Etienne Geoffroy Saint Hilaire in 1826 and was found "in a deposit of baboon votive mummies," Nelson said.

The micro-CT scans were conducted at Nikon Metrology in the U.K. Nelson recently presented the team's findings at the Extraordinary World Congress on Mummy Studies in Spain's Canary Islands.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus