Newly Discovered Fetus Is Youngest Egyptian Mummy on Record

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A miniature coffin discovered more than a century ago holds the remains of the youngest Egyptian ever embalmed as a mummy on record, researchers in England said.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the coffin revealed that the coffin didn't hold mummified internal organs, as researchers had suspected, but instead contains the tiny mummy of a human fetus, according to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England. The mummified fetus was likely at only 16 to 18 weeks of gestation when it died, likely from a miscarriage, museum officials said.

"This landmark discovery … is remarkable evidence of the importance that was placed on official burial rituals in ancient Egypt, even for those lives that were lost so early on in their existence," museum researchers said in a statement.

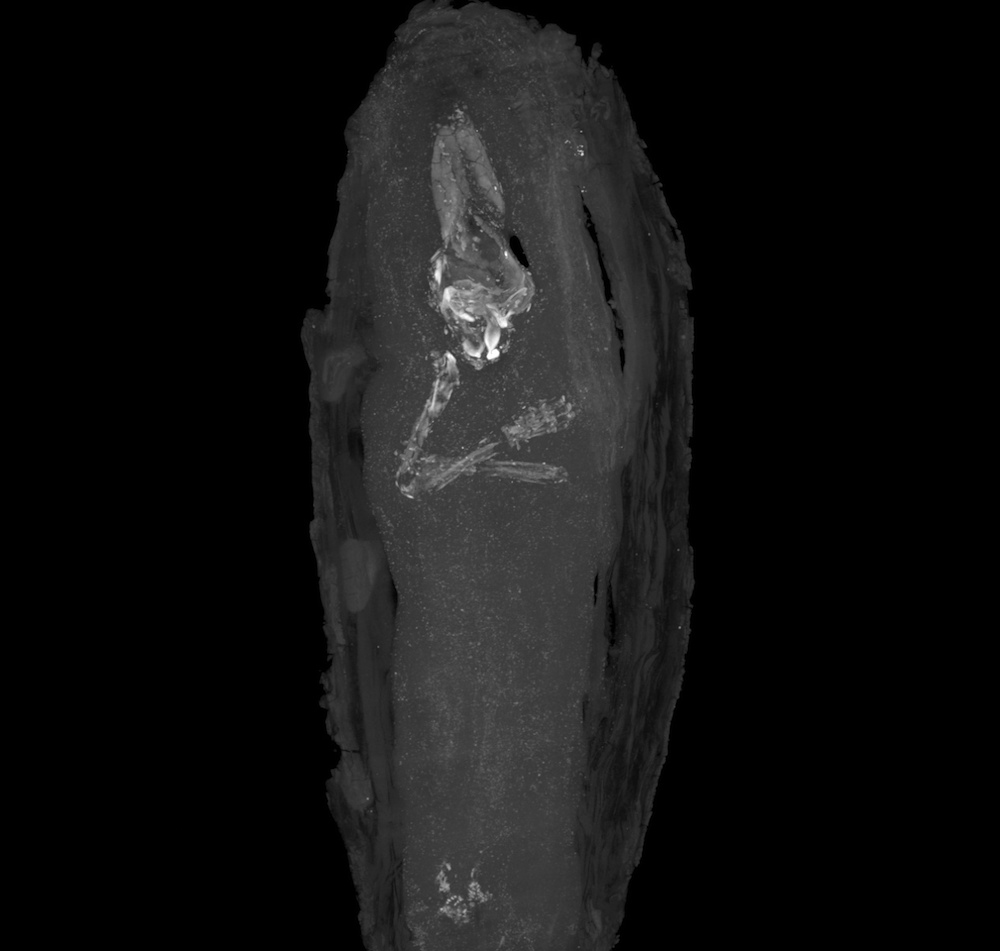

The British School of Archaeology originally uncovered the 17-inch-long (44 centimeters) coffin in Giza in 1907, and the Fitzwilliam Museum added the coffin to the museum collection that same year. The cedarwood coffin is a perfect miniature of a regular-size coffin from Egypt's Late Period, and likely dates to about 644 B.C. to 525 B.C., museum researchers said. It even has "painstakingly small" carvings on it, the researchers added. [Photos: 1,700-Year-Old Egyptian Mummy Revealed]

For years, museum curators assumed that the coffin held internal organs, which were routinely removed during the Egyptian embalming process. But curators found otherwise when they examined the coffin during preparations for the museum's bicentennial exhibition, "Death on the Nile: Uncovering the Afterlife of Ancient Egypt," which opened in February.

What they discovered in the coffin surprised them.

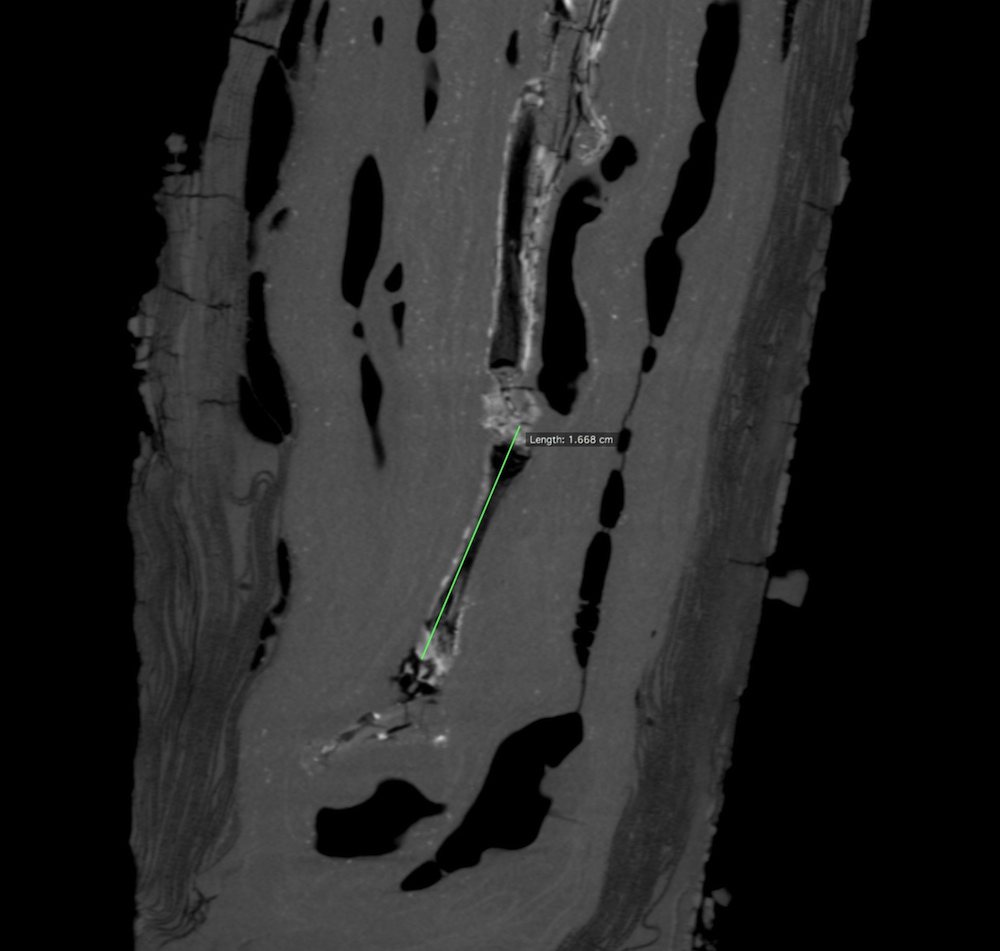

The wood casket contained a small wrapped package, bound in bandages and covered with molten black resin. An X-ray of the coffin gave inconclusive results, but suggested that the container held a small skeleton. So, the researchers examined the tiny bundle with a micro CT scan.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The resulting CT images revealed that the coffin held the remains of a tiny skeleton, which the researchers left undisturbed.

"CT imaging has been used successfully by the museum for several projects in recent years, but this is our most successful find so far," Dr. Tom Turmezei, recently an honorary consultant radiologist at Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge, England, said in the statement. "The ability of CT to show the inner workings of such artifacts without causing any structural damage proved even more invaluable in this case, allowing us to review the fetus for abnormalities and attempt to age it as accurately as possible."

The CT scans showed that the fetus already had five digits on each of its hands and feet, as well as clearly visible long leg and arm bones. However, it's unclear whether it was a boy or a girl, and it's unknown what caused the miscarriage, if that's what really happened, the researchers said.

The CT images also indicate that the fetus' arms are crossed over its chest. This intricate positioning, coupled with the extraordinary detail on the coffin, suggest that ancient Egyptians placed great importance on the fetus' burial, the researchers said.

"The care taken in the preparation of this burial clearly demonstrates the value placed on life, even in the first weeks of its inception," said Julie Dawson, head of conservation at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

This discovery isn't the only one of its kind. King Tutankhamun's tomb contained two mummified fetuses, which were estimated to be at 25 weeks and 37 weeks into gestation. Archaeologists have also discovered a few other examples of miscarried babies in ancient Egyptian burials, the researchers said.

The public can view the miniature coffin at the Fitzwilliam Museum until the exhibit ends on May 22.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus