Photos: 1,700-Year-Old Egyptian Mummy Revealed

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

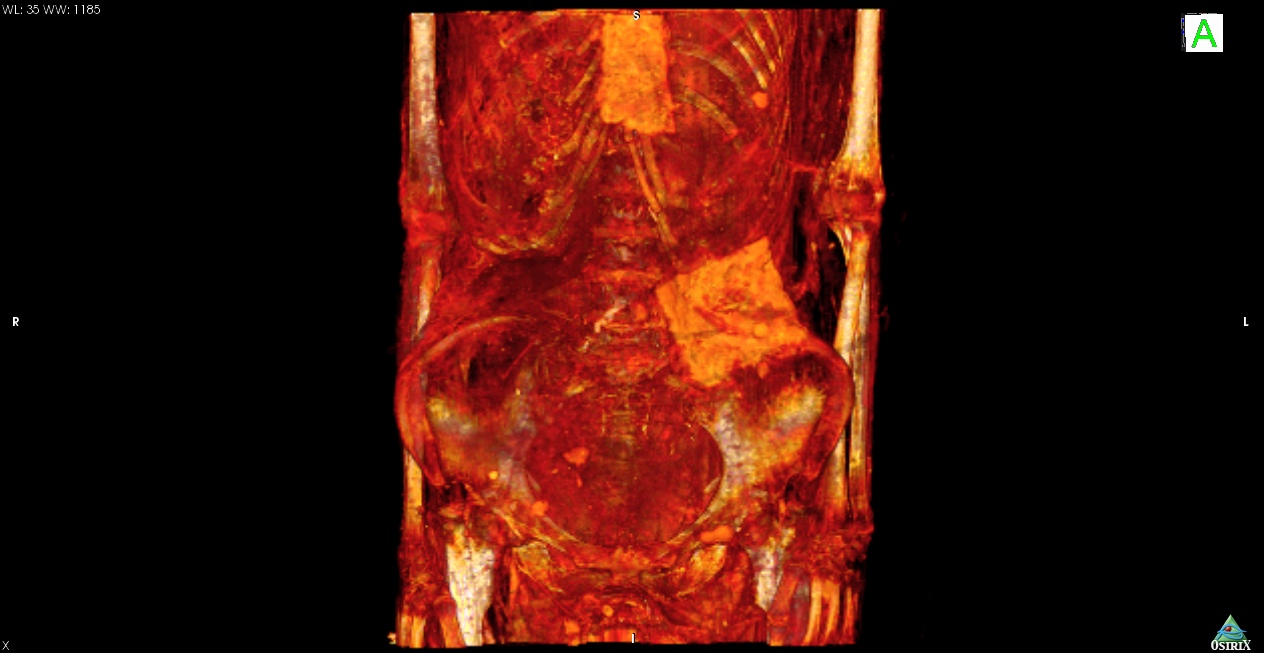

No Heart?

This 1,700-year-old mummy has a brain, no heart and plaques over her sternum and abdomen, say researchers. The plaques may have been intended to replace her heart, in a sense, and ritually heal the incision the embalmers had made to her perineum. Here, the mummy is being unboxed on the first day of a scanning session at the Montreal Neurological Institute. The mummy is now kept at the Redpath Museum at McGill University in Montreal.

Mummy face

While scientists don't know the female mummy's name, radiocarbon dating shows this woman lived around 1,700 years ago at a time when the Romans controlled Egypt, Christianity was spreading and mummification was in decline. Despite the changes underway this woman, and her family, opted for mummification.

The scans show she was about 5 feet, 3 inches in height (somewhat tall for her time), had dental problems that resulted in her losing many of her teeth, and died between the ages of 30 and 50. Here, a facial reconstruction of the mummy done by forensic artist Victoria Lywood.

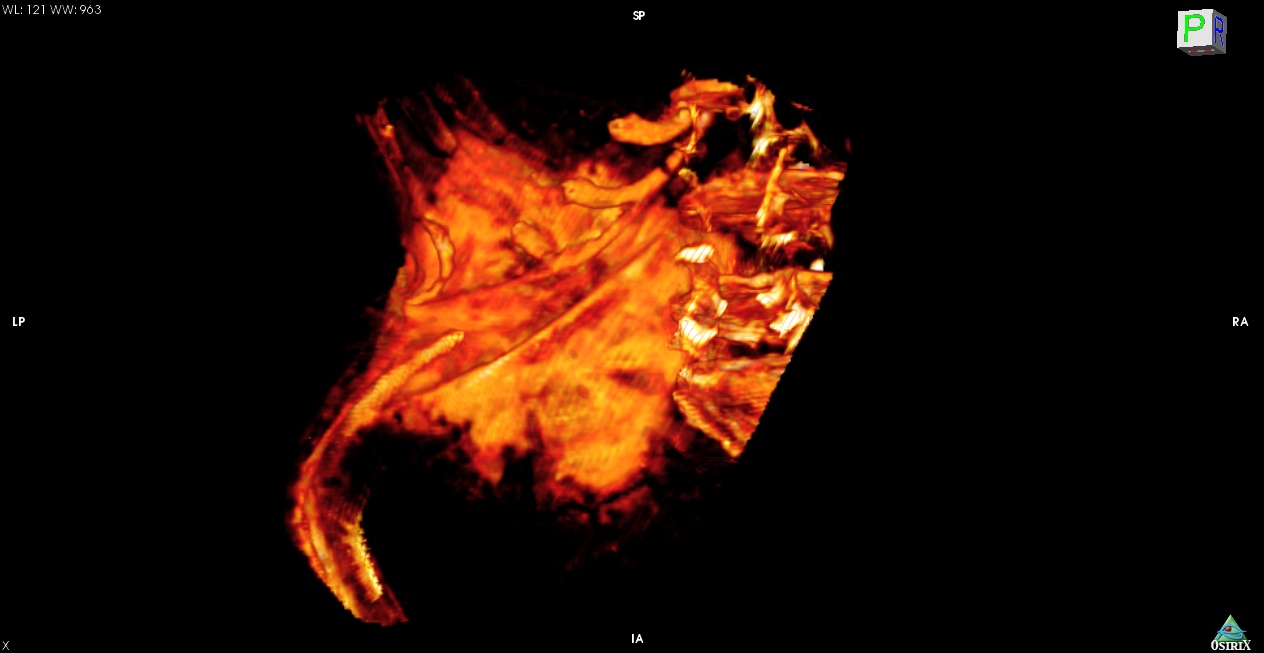

Mummy plaques

One of the most puzzling things revealed in the CT scans were two thin plaques made of something similar to cartonnage (a plastered material), placed over the female mummy's sternum and abdomen. They are located on the skin of the mummy, beneath the wrappings. The plaque over her sternum may be a replacement, of sorts, for her removed heart. Both plaques are visible in this image. The plaques may have been decorated, however the scanner cannot determine this.

Abdominal plaque

The abdominal plaque, seen here, is particularly puzzling. Mummies that were dissected through the abdomen would receive them, though this female mummy was dissected through the perineum.

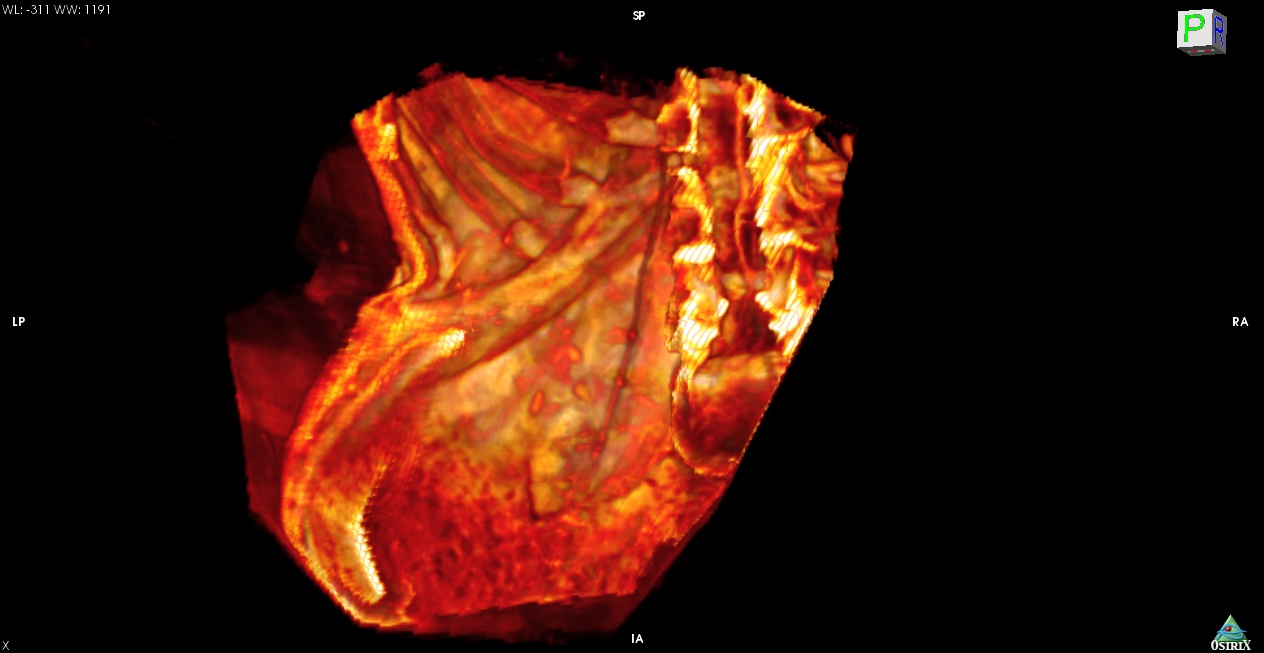

No cuts

When the researchers looked at the mummy's skin underneath the abdominal plaque (shown here) they found that it had not been cut. Although it cannot be said for certain why the plaque was put on the mummy, it may have been meant to ritually heal her after the embalmers had made the incision in her perineum. The embalmers may have thought the healing plaque would provide her with a better afterlife.

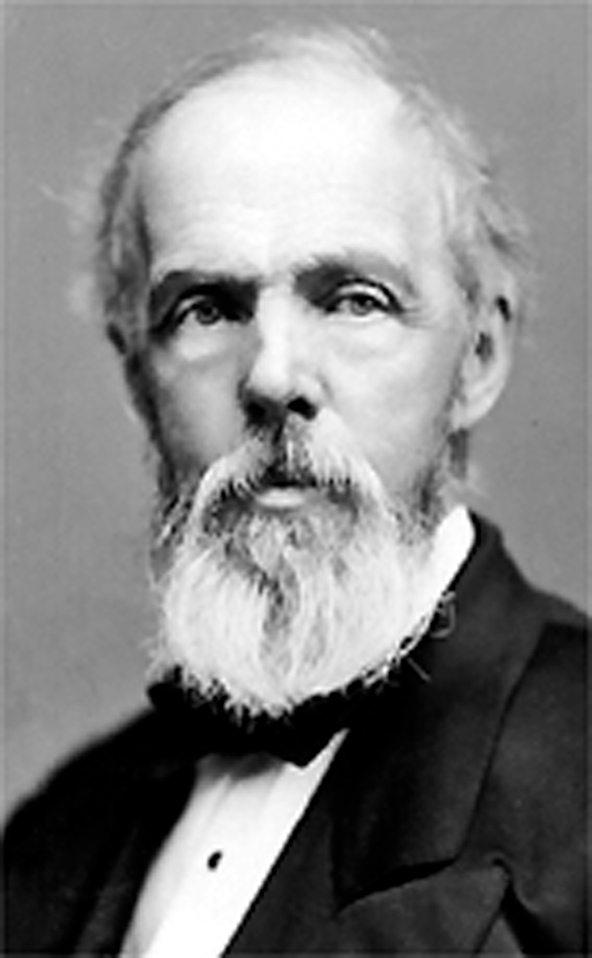

James Ferrier

The mummy was brought to Montreal from Luxor (Thebes) sometime before 1859 by James Ferrier, pictured here. The "Dictionary of Canadian Biography" notes that Ferrier, a businessman, travelled extensively in Africa, Europe and Asia and donated artifacts that he obtained to the Natural History Society of Montreal and McGill University. Ferrier had a successful career in politics, serving as mayor of Montreal and a Canadian senator. In 1884 he became chancellor of McGill.

Luxor

Luxor (Thebes) was an important Egyptian city for millennia, at times it had been Egypt's capital and important sites, such as Karnak Temple and the Valley of the Kings, were located nearby. By this woman's time, however, Luxor had been under Roman control for over two centuries and some traditional Egyptian practices, such as mummification, were in decline. This woman and her family chose to have it done anyways. While she was probably buried near Luxor scientists don't know exactly where.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Redpath Museum

Today her mummy is stored at McGill University's Redpath Museum in Montreal. The museum's collection has artifacts from around the world, including several mummies from Egypt. In addition, the museum has fossils and specimens from the natural world. Part of the museum's interior is pictured here.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus