Why Is China's Space Station Falling to Earth in the First Place?

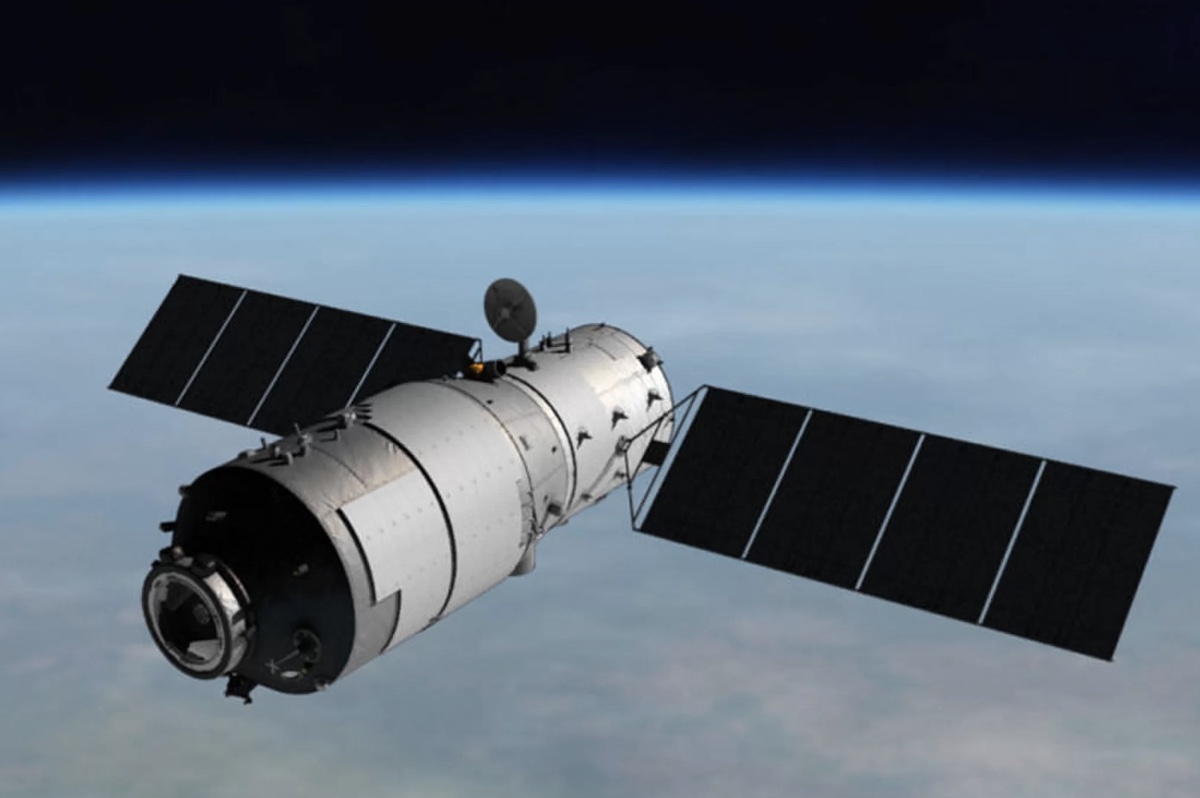

Space trackers are watching the skies closely this week for the end of China's Tiangong-1 space lab, which will likely fall back to Earth sometime during Easter weekend (March 30 to April 2). The one-module station is in an uncontrolled fall and will re-enter the atmosphere somewhere underneath the spacecraft's orbit, between 43 degrees north and 43 degrees south latitudes. No one knows exactly where and when yet.

Although the odds of getting hit by debris from the space station are extremely small — and only some pieces of Tiangong-1 will make it through the atmosphere — the craft's demise has some people asking why China's first space station is meeting such a seemingly reckless end.

The space station launched from China on Sept. 29, 2011, and received visits from three space missions. First came an uncrewed spacecraft (Shenzhou 8, in October 2011), which was followed by two crews (Shenzhou 9 and Shenzhou 10, in 2012 and 2013, respectively).

Tiangong-1 was a coup for the Chinese space program, which saw its first taikonaut (astronaut) mission in 2003, eight years before the space station's launch. Even when missions weren't in progress, the space station was transmitting information to Earth. Automated data was used for ocean and forest monitoring, and to gain information in support of the response to China's Yuyao flood disaster in 2013, according to the China Manned Space Engineering Office. [In Photos: A Look at China's Space Station That's Crashing to Earth]

But on March 21, 2016, that office announced that it was no longer communicating with the space station. "The functions of the space laboratory and target orbiter have been disabled after an extended service period of about two and a half years, although it remains in designed orbit," read a report from Chinese state media source Xinhua. The report added that Tiangong-1 was expected to burn up in the atmosphere after the station's orbit decayed, as happens naturally due to the forces of gravity and drag from the atmosphere.

It was unclear from the report if China deliberately turned off the telemetry connection to the space station or if that connection was lost. At the time, the country was already working on a successor space station, Tiangong-2, which launched just six months after communications with Tiangong-1 ceased.

Regardless of how contact with Tiangong-1 was lost, a lack of telemetry connection means Chinese engineers cannot control Tiangong-1, including steering its path into the atmosphere. China gave a summary of what to expect in a May 2017 statement to the United Nations. The country said that there is little danger to people on the ground, because "most of the structural components of Tiangong-1 will be destroyed through burning during the course of its re-entry."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

China also promised it would give information about Tiangong-1's re-entry through news reports and communication with the United Nations.

While pieces of the 18,740-lb. (9.4 tons, or 8,500 kilograms) space station are expected to make it to the ground, space experts have said Tiangong-1's re-entry likely won't leave as much debris behind as the 100-ton (90 metric tons) NASA Skylab space station did when it fell in a remote area of Australia in 1979. No injuries were reported in that event.

NASA (which could communicate with Skylab shortly before its re-entry) had attempted to steer the station into the ocean south of Cape Town, South Africa. Skylab, however, broke up at a different time than expected.

Originally published on Live Science.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus