Humans Cared for Sick Puppies Long Ago, Ancient Burial Shows

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Ancient people likely cared for a sick, domesticated pup for weeks on end before it died about 14,000 years ago during the Paleolithic era, a new study finds.

After it died, the dog was buried with the remains of another dog and an adult man and woman — making it not only the oldest burial of a domestic dog on record, but also the oldest known grave to contain both dogs and people, the researchers said.

This discovery suggests that even though the dog was young, sick and likely untrained as a result, ancient people still had an emotional bond with it, the researchers wrote in the study. This may explain why the people buried the animal with two of their own, the researchers said. [10 Things You Didn't Know About Dogs]

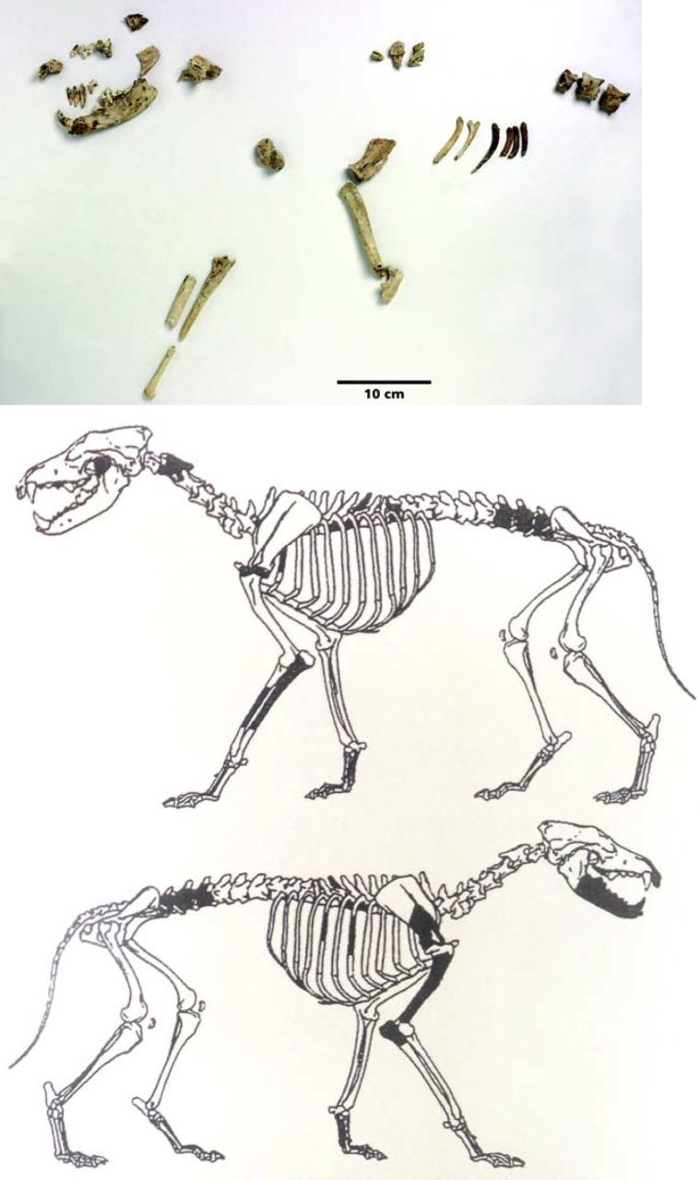

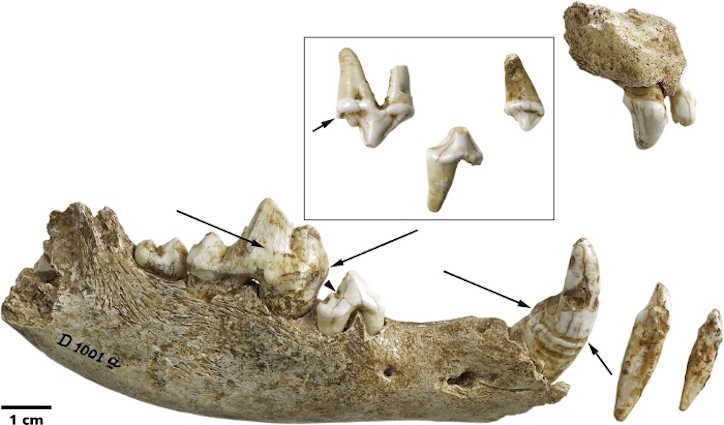

The grave itself was found in 1914 in Oberkassel, a suburb of Bonn in western Germany. Until now, however, researchers thought the burial contained two humans and just one dog. But a new analysis of the canid bones and teeth revealed that two dogs were in fact buried there: an older dog and a younger dog, which likely had a serious case of morbillivirus, better known as canine distemper.

The younger dog was about 28 weeks old when it died, the study's lead researcher, Luc Janssens, a veterinarian and doctoral student of archaeology at Leiden University in the Netherlands, said in a statement. A dental analysis showed that the pup likely contracted the disease at around 3 to 4 months of age, and likely had two or even three periods of serious illness, each lasting up to six weeks, Janssens said.

Canine distemper is a serious illness that has three phases. During the first week, infected dogs can show signs of high fever, lack of appetite, dehydration, tiredness, diarrhea and vomiting, the researchers wrote in the study. Up to 90 percent of dogs with distemper die during the second phase, when they can develop a stuffy nose, laryngitis and pneumonia. In the third phase, dogs experience neurological problems, including seizures.

There is now a vaccine for canine distemper, but unvaccinated dogs, as well as tigers and Amur leopards, can still die from the virus.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Given the severity of the disease, the ancient pup would have likely died right away unless it received intensive human care, the researchers said. "This would have consisted of keeping the dog warm and clean [from] diarrhea, urine, vomit [and] saliva," as well as giving the pup water and possibly food, the researchers wrote in the study.

"While it was sick, the dog would not have been of any practical use as a working animal," Janssens said. "This, together with the fact that the dogs were buried with people, who[m] we may assume were their owners, suggests that there was a unique relationship of care between humans and dogs as long as 14,000 years ago."

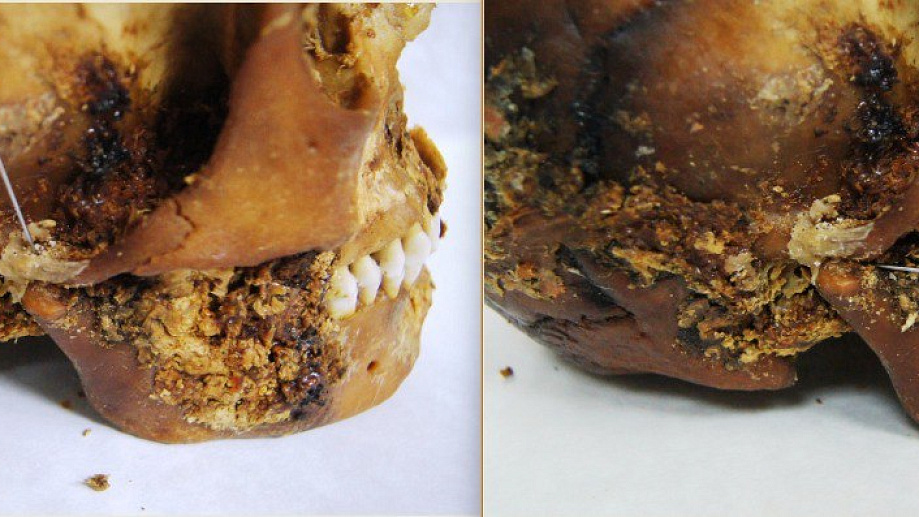

The humans buried with the dogs had medical problems of their own. The roughly 40-year-old man had two healed bones, one on his arm and the other by his clavicle. He and the roughly 25-year-old woman also had moderate-to-severe dental disease, the researchers noted. [7 Bizarre Ancient Cultures That History Forgot]

The grave also contained several artifacts, including a bone pin, a sculpture of an elk made from elk antlers, the penis bone of a bear and a red-deer tooth.

Although this finding is the oldest known domestic dog burial, it's not the only ancient one. Other dog burials have been dated to about 11,600 years ago in the Near East, and archaeologists have found others dating to about 8,500 to 6,500 years ago in Scandinavia and about 8,000 years ago at the Koster Site in Illinois, the researchers said.

The study was published online Feb. 3 in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus