Chameleons' Secret Glow Comes from Their Bones

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Blending seamlessly into one's surroundings is known as being "chameleon-like" for a good reason — chameleons shift the colors and patterns of their skin to hide from predators in plain sight, or to communicate during social interactions with other chameleons.

But there's a secret, illuminated layer to chameleons' colorful signaling: Scientists recently discovered that the lizards' bones, particularly on their heads and faces, fluoresce through their skin, creating glow-in-the-dark patterns.

"Chameleons are already famed for their exceptional eyes and visual communication, and now they are among the first known terrestrial squamates [scaled reptiles] that display and likely use fluorescence," the scientists wrote in the study. [Photos: How Chameleons Change Color]

Biologists have long known that bones glow under ultraviolet (UV) light, but the researchers were astonished to learn that chameleons could harness this characteristic to display visible fluorescent patterns through their skin, study co-author Frank Glaw, a herpetology curator at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology (ZSM) in Munich, Germany, said in a statement.

"That animals use this phenomenon to fluoresce themselves has surprised us and was previously completely unknown," Glaw said.

Fluorescence, in which special structures glow in the presence of light, differs from bioluminescence, a process that describes light generated by a chemical reaction between compounds in an animal's body. Fireflies, some types of fungi and numerous deep-sea creatures are bioluminescent, while fluorescent animals include scorpions, corals, jellyfish, a rare type of sea turtle, and now, chameleons.

The study's authors looked at 160 specimens representing 31 species in the Calumna genus, a group of chameleons native to Madagascar, and 165 specimens from 20 species of the Furcifer genus, found in Madagascar and parts of Africa. They photographed living animals in their habitats as well as preserved specimens, using UV light to illuminate the chameleons and reveal their glowing patterns.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

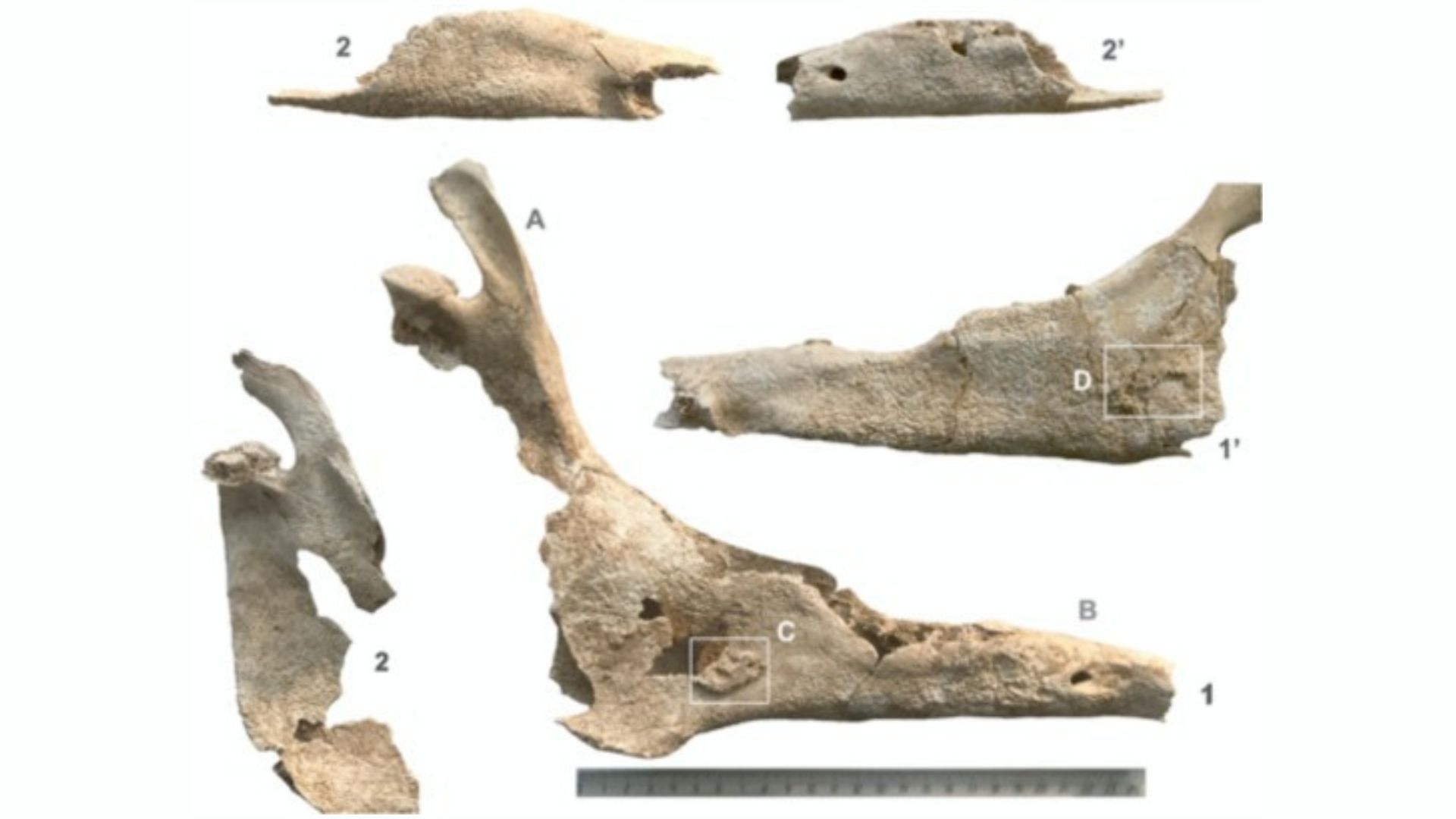

Next, they turned to micro-computed tomography — 3D X-ray imaging on the microscopic level — to literally connect the dots, matching the glowing spots in the patterns to raised bumps in the lizards' bones known as tubercles, which provided the source of the glow.

Nearly all the species revealed previously unseen blue patterns on their skin when under UV light, the researchers discovered. Most of the lizards displayed patterning on their heads, but some showed fluorescent markings across their bodies, the study's first author David Prötzel, a ZSM doctoral student, said in the statement. The patterns appeared blue because the lizards' thin outer layer of skin serves as a filter, nudging the fluorescence toward the blue end of the spectrum, according to the study.

The thin skin stretched over the bumps serves as a window, allowing UV light to reach the bone and then enabling the shine to reflect through the skin. In shadowy, humid forest habitats, intermittently-visible fluorescent patterns could allow the lizards to signal each other without drawing the attention of predators, the study authors wrote.

Patterns tended to cluster around the chameleons' eyes and the front of their heads, areas known to be important for communication between individuals. On average, male specimens across species displayed more patterning than females; while it is still uncertain how the chameleons may use fluorescence, this male-skew suggests it may play a role in sexual selection, though further study will be required to say for sure, the scientists explained.

"Fluorescence in terrestrial vertebrates has been underestimated until now, and its role in the evolution of ornamentation remains largely unexplored, but this is a promising avenue for future research," the study authors reported.

The findings were published online Jan. 15 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus