Many Vietnam Vets May Have Cancer-Causing Parasites: What Are Liver Flukes?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Hundreds of Vietnam War veterans may be infected with parasites called liver flukes, which can sometimes lead to cancer, recent research suggests.

A recent study from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) found that, out of 50 blood samples submitted from Vietnam veterans, more than 20 percent tested positive for antibodies against liver flukes, according to the Associated Press.

The findings could mean that many Vietnam veterans have "silent" infections with the parasite, meaning they don't have any symptoms. However, the results are preliminary, and it's possible that not all of the veterans who tested positive actually have the parasite, the researchers said. Still, the results were "surprising," study researcher Sung-Tae Hong, of Seoul National University in South Korea, told the Associated Press.

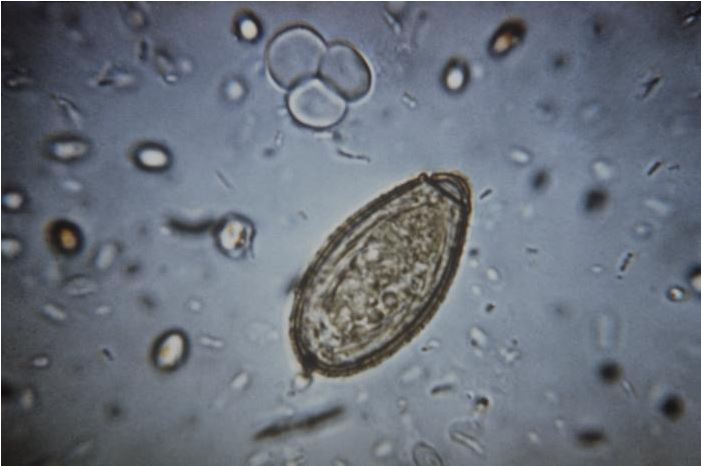

Liver flukes are small, flat parasitic worms that can infect the liver, gallbladder and bile ducts. People become infected when they eat raw or undercooked freshwater fish that have the parasites, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Although liver-fluke infections are rare in the United States, it's estimated that 35 million people worldwide are infected with the parasites at any one time, mostly in Asia and Eastern Europe, according to a 2011 review article.

There are three main types of liver flukes that cause human infection: Clonorchis sinensis, which is common in rural parts of China and Korea; Opisthorchiasis viverrini, which is found in Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia; and Opisthorchis felineus, which is found in a wide geographical area, including Eastern Europe, Central Asia and Siberia, according to the World Health Organization. [Images: Human Parasites Under the Microscope]

Most people who become infected with liver flukes have no symptoms, but some may experience indigestion, abdominal pain, diarrhea and constipation, according to the CDC. However, over long periods, infection with liver flukes can cause chronic inflammation in the bile ducts, resulting in scarring of the ducts and destruction of nearby liver cells, according to the WHO. What's more, the inflammation and scarring of the bile duct can lead to cancer of the bile ducts, which is called cholangiocarcinoma.

This type of cancer is rare in Western countries, with only about 7 cases per 1 million people, according to the 2011 review. In the United States, an estimated 8,000 people are diagnosed with bile-duct cancer each year, according to the American Cancer Society.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Symptoms of the cancer can include jaundice (yellowing of the skin), pain in the abdomen, dark urine, fever, itchy skin, vomiting and unexplained weight loss, according to the VA. For people with early-stage bile-duct cancer, about 15 to 30 percent survive at least five years following their diagnosis, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology. However, if the cancer has spread to a distant part of the body, the five-year survival rate is 2 percent.

Last year, the Associated Press raised concerns about cholangiocarcinoma tied to liver-fluke infections in veterans when it reported that 700 Vietnam veterans with the rare cancer had been seen at the VA in the past 15 years.

However, the VA has not yet made a recommendation for Vietnam veterans to get tested for liver flukes or bile cancer because the department is still investigating the issue.

"We are taking this seriously," Curt Cashour, a spokesperson for the VA, told the Associated Press. "But until further research [is done], a recommendation cannot be made either way."

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus