Frozen Hair Yields First Ancient Human Genome

A few tufts of hair frozen in the permafrost of Greenland for more than 4,000 years have allowed scientists to sequence the genome of an ancient human for the first time.

The hairs belonged to a member of the ancient Saqqaq culture of Greenland, the first humans known to inhabit the icy island. Scientists have long wondered where the Saqqaq came from and whether or not they were the ancestors of today's modern Inuit and Greenlanders. The new findings, detailed in the Feb. 11 issue of the journal Nature, have helped to settle that question.

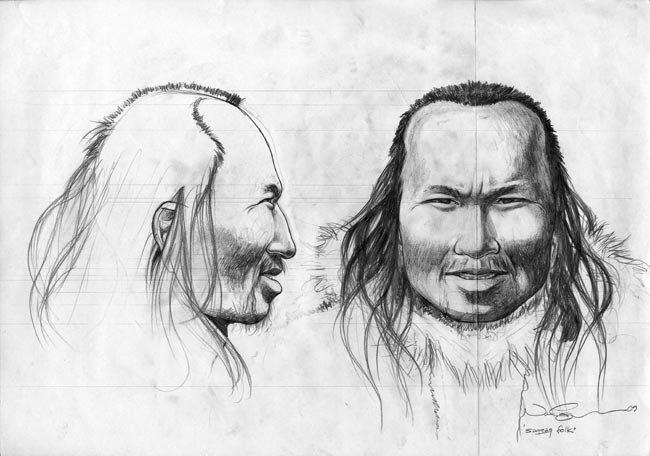

The hairs also tell about the individual, which scientist have dubbed "Inuk," meaning "human" or "man" in the Greenlandic language, giving us insight into what our ancient human ancestors looked like.

The results suggested Inuk was a male with brown eyes, dark skin, type A+ blood, shovel-shaped front teeth and was genetically predisposed to baldness and dry earwax. (Because Inuk clearly still had hair when he died, the scientists think he must have died young.) He also likely had a metabolism that was well-adapted to a cold climate.

Fortunate find

Eske Willerslev, of the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, had long been searching Greenland for human remains that could be tested for DNA fragments.

"I was freezing my butt off up in the high Arctic trying to recover human remains to do DNA testing on," he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By chance, was discussing the early settling of the Arctic with the director of the Natural History Museum in Denmark, Dr. Morten Meldgaard. As it happened, Meldgaard had participated in several excavations in Greenland in the 1980s and told Willerslev about a large tuft of hair that had been found preserved in the permafrost, or frozen soil.

Willerslev got permission to test the tufts, which hold up better and are generally less contaminated by foreign DNA than other remains, such as bones, which are porous and subject to mold and bacteria.

The genome sequence that resulted from the team's efforts is about 80 percent complete and comparable in quality to sequences of the modern human genome, Willerslev said. That's a substantial step up from previous sequences of the woolly mammoth genome, also made from hair tufts, and Neanderthal genomes, which are not nearly as complete.

The completeness of the genome from just one sample is also significant because besides four small pieces of bone and hair, no human remains have been found of the first people that settled the New World Arctic.

This sequencing can help "say something about the origin of this extinct culture," Willerslev said.

Early migration

Archaeologists had long wondered whether the Saqqaq were ancestors of the modern Inuit, or perhaps were Native Americans who penetrated farther north than other cultures, or even a completely separate culture that came in through its own migration.

Inuk's genome suggests that it's the latter case.

Inuk proved to be most closely related to three Old World Arctic populations, the Nganasans, Koryaks and Chukchis of the Siberian Far East. So the genetics suggest that they are not direct ancestors of the peoples that currently live in the New World Arctic.

The genome sequence suggests that Inuk's ancestors crossed into the New World from north-eastern Siberia between 4,400 and 6,400 years ago in a migration wave that was independent of those of Native Americans and Inuit ancestors.

And it turns out that "the estimate that you get from the genome actually fits the archaeological information pretty well," Willerslev said. The archaeological record shows the earliest presence in the high Arctic of Greenland and Canada to be about 5,500 years ago.

Just how Inuk's ancestors got to the New World though isn't known. It most likely wasn't through any land bridge.

"There was no land bridge available between Siberia and Alaska 5,500 years ago. That land bridge had already disappeared," Willerslev said.

They could have crossed frozen ice, but ultimately, "no one knows," Willerslev said.

What happened to the Saqqaq is equally as mysterious.

"Basically no one knows what happened," Willerslev said. The data have so far suggested "that they died out in the New World." But whether it was climate, competition or some other influence that caused them to go extinct isn't known and can't be gleaned from genetic data.

Willerslev expects that the technique his team used could help them learn more about other ancient cultures, such as the native populations of South America, whose diversity was wiped out after Europeans arrived there, and native Tasmanians, who also disappeared quickly after European contact.

"I think it will be something that we will see more of in the coming five years," Willerslev said.

- Top 10 Missing Links

- Top 10 Things that Make Humans Special

- Why Did Humans Migrate to the Americas?

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.