Doggone: Your Best Friend Is Red-Green Colorblind

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

If you're ever deciding between throwing a red ball or a green ball for your dog to fetch, know this: It doesn't matter to Fido because dogs are red-green colorblind, a new small study suggests.

Researchers in Italy tested 16 dogs on their color vision and found the canids had red-green colorblindness, a condition known as deuteranopia that affects about 8 percent of men and 0.5 percent of women with Northern European ancestry, according to the National Eye Institute.

The finding suggests that, "if you are planning to train your dog to fetch a ball that fell on the green grass of your garden, think of using a blue, and not red, ball," said study lead researcher Marcello Siniscalchi, a professor in the Department of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Bari, in Italy. [10 Things You Didn't Know About Dogs]

It's a common misperception that dogs see only in black and white. Rather, research shows that dogs' eyes have two kinds of cones, the photoreceptor cells responsible for color vision. One cone type is sensitive to yellow and another to blue, Siniscalchi said. This suggests that dogs can see yellows, blues and their different combinations, he said. (Humans have three types of cones that are sensitive to red, green and blue wavelengths.)

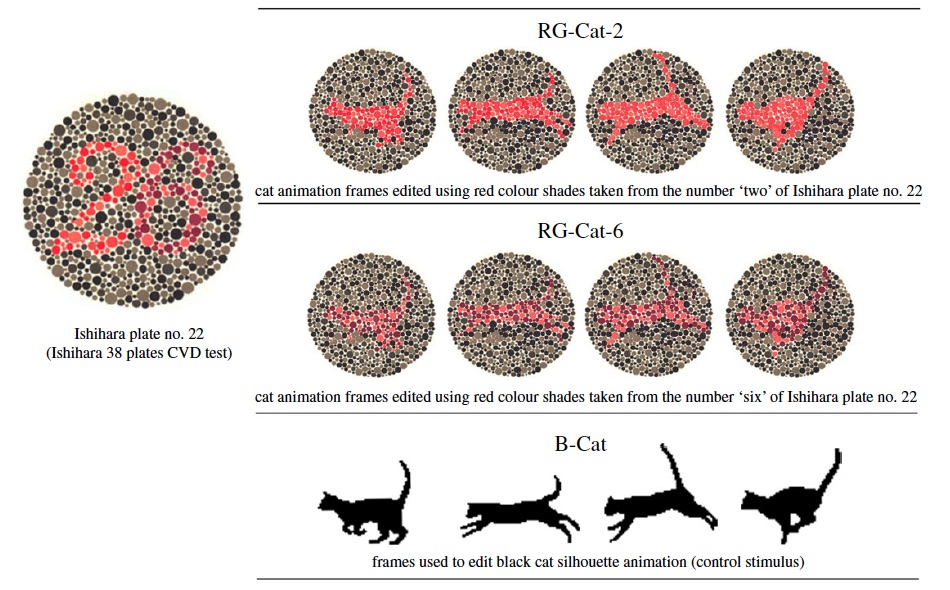

Although computer models had indicated that dogs have red-green color blindness, Siniscalchi wanted to test it directly. So, he used a variation of the Ishihara Color Vision Test — a series of colored circles that have differently colored numbers in them. If a person can't see a red-colored "12" in a green circle, it's an indication that he or she is red-green colorblind.

But Siniscalchi put a fun twist on the test: Instead of using numbers, he used an animation of a running cat.

When the running cat was shown in bright red against a mottled green background, most of the dogs noticed it right away, Siniscalchi said. But when the dogs saw the image with a little less dramatic color variation — a speckled light- and dark-red cat against a mottled green background — many of the dogs didn't appear to notice the feline.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The present work showed, for the first time directly, canine red-green blindness by using a modified test of color vision in humans," Siniscalchi said.

The red-green colorblindness finding isn't unexpected, however. Most people think of dogs as diurnal, that is, active during the day. But "we must not forget that in an evolutionary perspective, dogs are crepuscular [active at dawn and dusk]," Siniscalchi said.

Color vision isn't crucial for survival and hunting during twilight periods, he noted.

Because most pets are active during the day, he advised that if a dog's safety is at stake, don't use red- and green-colored objects. For instance, on the off-chance that a pet owner would set up an obstacle course with red jump markers on the green grass, "the dog will see [both] as shades of yellow, resulting in an accident with possible injuries," he said.

Siniscalchi and his colleagues studied both purebreds and mutts, including three Australian shepherds, one Épagneul Breton, one weimaraner, one Labrador retriever and 10 mixed-breed dogs. But because the study was small, the results need to be confirmed in a larger experiment, he said.

The study will be published online today (Nov. 8) in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus