What Is Leptospirosis? Dozens of Cases Suspected in Puerto Rico

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Dozens of people in Puerto Rico are suspected to have contracted leptospirosis, a bacterial illness, in the wake of Hurricane Maria, and several people have died from the disease.

Yesterday (Oct. 24), officials in Puerto Rico said they had confirmed two deaths from the disease, according to CBS News. Another 74 cases of suspected leptospirosis are being investigated, CBS reported. (In total, 51 people have died in Puerto Rico as a result of Hurricane Maria.)

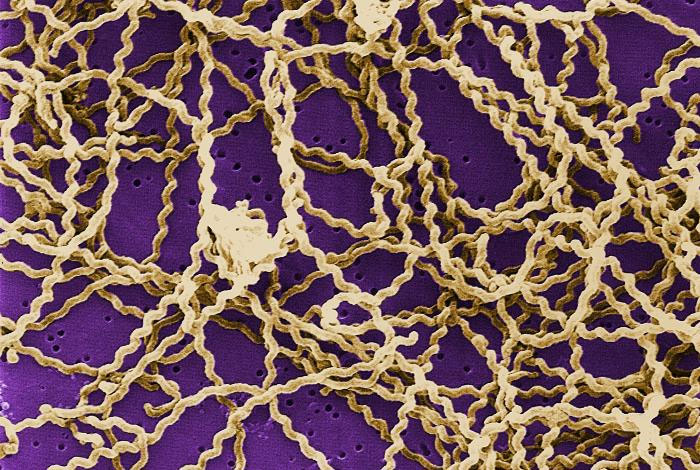

Leptospirosis is caused by a spiral-shaped bacterium known as Leptospira, which can infect animals and people.

People can become infected with Leptospira bacteria when they come into contact with the urine of infected animals, or with an environment that's been contaminated with the infected urine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For example, the bacteria can contaminate water or soil, and survive there for months, the CDC said. [27 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

Outbreaks of leptospirosis typically happen when people are exposed to the bacteria through contaminated water, such as floodwaters, the CDC said. The bacteria do not typically spread from person to person.

The devastation caused by Hurricane Maria created conditions that increase the risk that people will contract certain infectious diseases, including leptospirosis, according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America, which recently sent a letter to Congress urging action to prevent the spread of disease in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands after Hurricane Maria.

"With water supplies still not restored and sewerage systems disrupted to many affected areas, individuals may turn to rivers, springs or other ad hoc water sources. This approach, along with the presence of floodwaters, increases the risk of illness caused by waterborne pathogens," including leptospirosis, the letter said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Some people infected with Leptospira bacteria may have no symptoms, according to the CDC. Others may experience a high fever, chills, muscle aches, vomiting, diarrhea and photophobia (eye discomfort when exposed to bright light). In severe cases, the infection can lead to kidney damage, brain inflammation, liver failure and death, the CDC said.

Puerto Rico typically has around 60 to 95 cases of leptospirosis per year, and cases were expected to rise after the hurricane, CNN reported. Healthy officials are now awaiting lab results for the suspected cases, which are being carried out by the CDC.

Leptospirosis can be treated with antibiotics, usually doxycycline or penicillin. Treatment should begin as early as possible to reduce the severity and duration of the disease, the CDC said.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus