Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

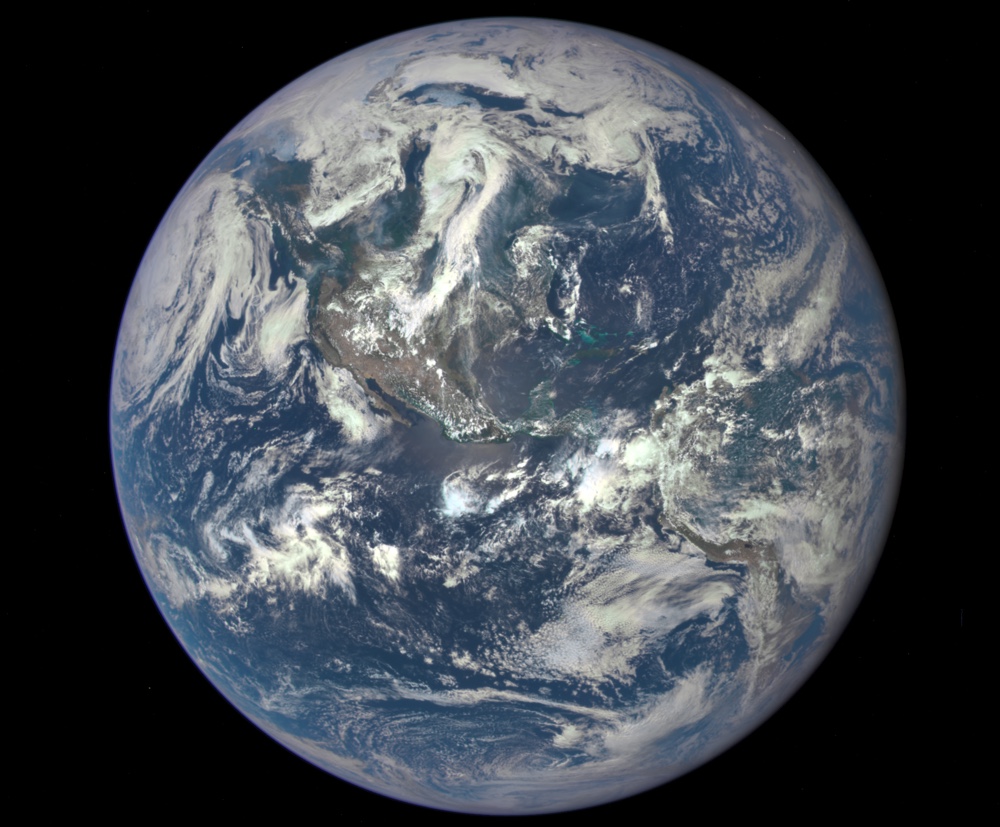

The amount of carbon dioxide that humans will have released into the atmosphere by 2100 may be enough to trigger a sixth mass extinction, a new study suggests.

The huge spike in CO2 levels over the past century may put the world dangerously close to a "threshold of catastrophe," after which environmental instability and mass die-offs become inevitable, the new mathematical analysis finds.

Even if a mass extinction is in the cards, however, it likely wouldn't be evident immediately. Rather, the process could take 10,000 years to play out, said study co-author Daniel Rothman, a geophysicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [7 Iconic Animals Humans Are Driving to Extinction]

However, slashing carbon emissions dramatically in the coming years may also be enough to prevent such global catastrophe, said Lee Kump, a geoscientist at Pennsylvania State University who was not involved in the study.

Carbon and death

Over Earth's 4.5-billion-year history, life has seen a lot of boom and bust times. In the past half-billion years alone, five major extinctions have wiped out huge swaths of life: the Ordovician-Silurian mass extinction, the Late Devonian mass extinction, the Permian mass extinction, the Triassic-Jurassic mass extinction and the Cretaceous-Tertiary mass extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs. The most severe was the Permian extinction, or "The Great Dying," when over 95 percent of marine life and 70 percent of land-based life died off.

All these major extinctions have one similarity.

"Every time there's been a major mass extinction — one of the big five — there's been a serious disruption of the global carbon cycle," Rothman said. It could be a direct link between CO2 and death due ocean acidification or an indirect link, as carbon dioxide emissions can warm a planet to unlivable temperatures and have even been linked with volcanic eruptions and the related cooling of the atmosphere.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For instance, at the end of the Permian period, about 252 million years ago, ocean carbon dioxide levels skyrocketed, marine rocks reveal. (Carbon dioxide that is in the air gradually dissolves into the ocean's surface and eventually enters the deep ocean.) However, carbon doesn't always equal assured doom for the planet. It's possible that a change in carbon levels in the atmosphere and oceans are markers for rapid environmental change, which could be the underlying cause of extinctions. In addition, rocks from the past reveal many other "carbon excursions" — or rises in atmospheric or ocean levels of carbon — that did not result in mass extinctions, Rothman said. [Ocean Acidification: The Other Carbon Dioxide Threat]

Fast time and slow time

So what distinguishes the deadly carbon excursions from the ones that don't cause mass dying?

In the new study, which was published Sept. 20 in the journal Science Advances, the scientists assumed that two factors may play a role: the rate at which carbon levels increase, and the total amount of time that change is sustained, Rothman said.

To calculate those values, Rothman looked at data on carbon isotopes, or versions of the element with differing numbers of neutrons, from rock samples from 31 geologic periods over the past 540 million years. Determining the length and magnitude of rises in atmospheric carbon can be tricky because some periods have thorough rock samples while others are sparsely represented, Rothman said.

From that data, Rothman and his colleagues identified the rates of carbon change and total carbon input that seemed to be correlated to extinctions in the geologic record. Then, they extrapolated to the present day, in which humans are adding carbon to the atmosphere at a furious rate.

Rothman calculated that adding about 310 gigatons of carbon to the oceans was enough to trigger mass extinctions in the past, although there is huge uncertainty in that number, Rothman said.

"Most every scenario that's been studied for how things will play out, as far as emissions are concerned, suggest on the order of 300 gigatons or more of carbon will be added to the oceans before the end of the century," Rothman said.

What happens the day after that threshold is reached?

"We run the risk of a series of positive feedbacks in which mass extinction could conceivably be the result," Rothman said.

Of course, those effects wouldn't be felt immediately; it could take 10,000 years for the die-off to result. And there's a lot of uncertainty in the estimates, Rothman added.

"I think it's a really useful approach, but there are always limitations when we're working in deep time," Kump told Live Science. "One of the limitations is that Rothman had to accept the state of our understanding of the timing and duration of these disturbances."

But even with that uncertainty, "clearly the rate of fossil fuel burning today rivals, if not exceeds, the rate of carbon cycle perturbation in the past" associated with mass extinctions, Kump said.

Because the rate of carbon rise is so steep currently, the best option for preventing eventual catastrophe is to ensure the duration of the carbon increase is short, he said.

"If we can rein ourselves in, we can avoid the Permian catastrophe," Kump said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus