Toilet Paper Power: How Used Bathroom Tissue (Yuck) Could Generate Electricity

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Are we flushing away a greener future?

Perhaps, according to scientists who found a way to turn used toilet paper into electricity.

The researchers found that they could generate energy from waste toilet paper with about the same efficiency as a natural gas plant and for the same cost as in-home solar panels, they said.

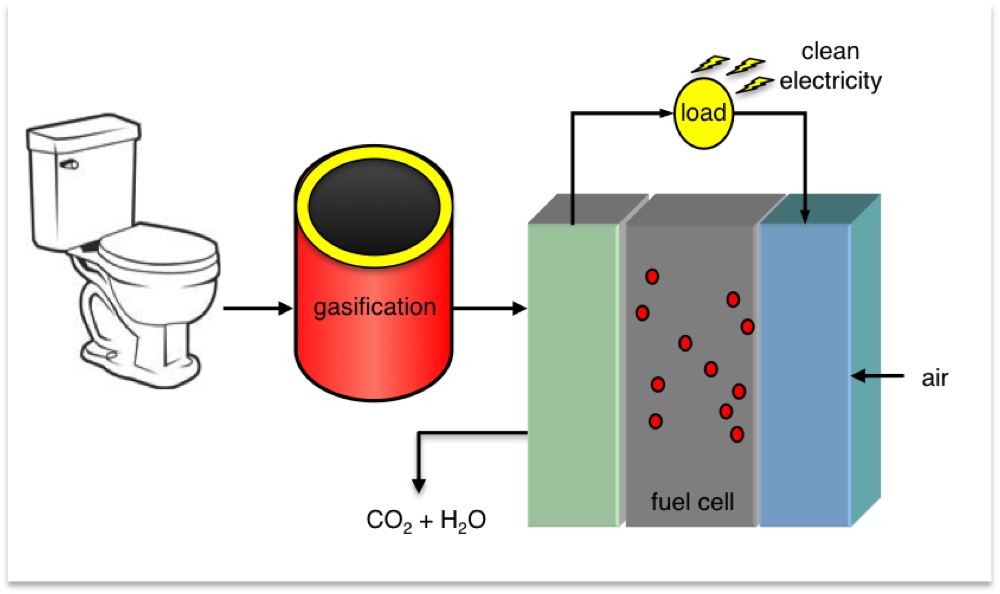

For their study, the sustainable-chemistry researchers from the University of Amsterdam and Utrecht University in the Netherlands developed a two-step procedure with the goal of returning grimy toilet paper to a state where it most resembles the wood it was made from. So, they collected dirty toilet paper from the sludge at water-treatment plants. Then they dried it out and converted it into a gas in a chamber that can reach up to 1,650 degrees Fahrenheit (900 degrees Celsius). They removed tars, ashes and moisture from the gas to leave behind mostly methane, carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide. Those gases were fed into solid-oxide fuel cells, which maintain very high temperatures to generate low-emission electricity from methane.

The process is designed to maximize efficiency and sustainability: Residual heat created by the fuel cell is then used to dry out the next round of toilet paper, and the entire process gives off about one-sixth the carbon emissions of a coal plant, according to the research detailed in August in the journal Energy Technology.

According to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, this puts toilet paper power on a par with renewable resources in terms of emission rates. Thanks to the closed-loop nature of this system and the increased efficiency of the fuel cell, this new process captures two to three times more electricity than that from merely burning used toilet paper, the researchers said. [Poop Sausage to Pee Drinks: 7 Gross 'Human Foods']

If all the toilet paper in the Amsterdam region, the researchers' native country, were converted to electricity daily, then water treatment facilities would save 40 percent of their energy on separating toilet paper from water, the researchers calculated. Furthermore, the captured energy could power as many as 6,400 homes, they added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But don't go saving your used toilet paper just yet. Even though plants could acquire the paper at negative cost because it's treated as waste rather than a resource, fuel-cell technology hasn't quite reached the point where building these systems is cost-effective, the researchers said.

Editor's Note: This article was updated to state that converting all the toilet paper in the Amsterdam region (not the Netherlands) could save energy at water treatment facilities.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus