Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A high-status Viking warrior who was thought to be a man turns out to be a woman, a new DNA analysis finds.

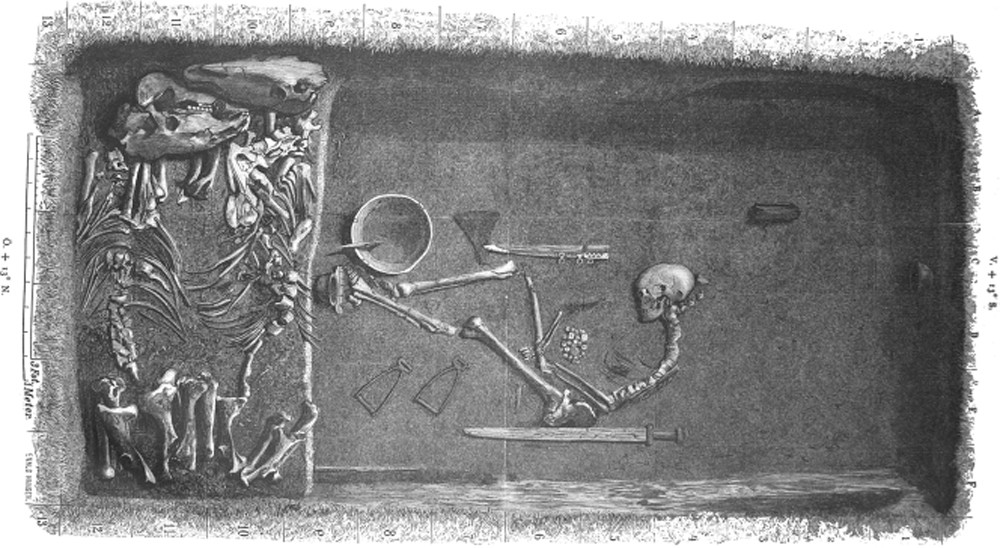

The remains of the warrior were buried with an array of warlike accessories, including arrows, swords and warhorses.

The findings raise questions about the role of women in Viking society, which has historically been thought of as a testosterone-fueled, patriarchal culture, the researchers say. [In Photos: Viking Voyage Discovered]

"The identification of a female Viking warrior provides a unique insight into the Viking society, social constructions and exceptions to the norm in the Viking time-period. The results call for caution against generalizations regarding social orders in past societies," the researchers wrote in their paper, published online Sept. 8 in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology.

Trading town

Scientists unearthed the remains of the warrior from one of the largest Viking burials ever discovered: a ring of graves that encircle the medieval town of Birka, on the island of Björkö, in Sweden. Starting in the eighth century, the town of Birka was a thriving trade center, bustling with artisans, warriors and traders. Goods from far-flung regions of the world — such as the Byzantine Empire, Asia and central Europe —would pass through the town before making their way to other places in the Viking world. The town, which typically supported between 700 and 1,000 inhabitants, was thus somewhat culturally different from the areas around it, the researchers noted. Since the 1800s, more than 3,000 graves have been unearthed in Birka, the researchers wrote.

One of the graves was that of a presumed Viking warrior, whose remains were buried with a range of warlike weapons. For decades, however, researchers assumed that the burial was that of a high-status male officer. [Fierce Fighters: 7 Secrets of Viking Seamen]

In the 1970s, however, researchers noticed the slender build of the long bones, as well as distinctive features on the hip bones, and identified the body as belonging to a woman. But that hypothesis was controversial; many experts discounted the notion that the warrior could be a woman. In 2016, a bone analysis once again showed that the burial belonged to a woman, though many scholars remained skeptical.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Genetic analysis

To help settle the question, Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson, an archaeologist at Uppsala University in Sweden, and her colleagues took DNA samples from the skeleton. They found that the warrior was, unequivocally, a woman, with genetic affinities to modern-day people who currently live in the Orkney Islands, Iceland, England, Scotland and Scandinavia. Based on strontium isotopes (versions of strontium with different numbers of neutrons) from her teeth, which more closely matched levels found in other areas, the team found that the woman had not grown up in Birka but had relocated there after childhood.

The grave goods that were buried with her — such as a sword, an ax, a spear, arrows, a battle knife, two shields and two horses — suggest that the woman was a professional warrior, the researchers wrote in the new study. The grave also included a set of gaming pieces, which suggests a knowledge of tactics or strategy, implying she was a "high-ranking military officer," the researchers wrote.

The researchers who worked on this new study are not convinced that Viking society was an egalitarian utopia. It's not clear how common such a role was for women, they said. For instance, no other tombs with clear Viking warrior women have ever been discovered, the researchers wrote in the study.

Still, "the results suggest that women, indeed, were able to be full members of male dominated spheres," the researchers wrote.

Heightened scrutiny

Almost as soon as the genetic results were published, scholars began to question the interpretation that the woman was a warrior. One of the biggest issues is that the body itself bears no sign of the traumas typically associated with battle.

For instance, Judith Jesch, director of the Centre for the Study of the Viking Age at the University of Nottingham in England, expressed skepticism about some of the paper's conclusions.

For instance, on her blog, Jesch criticized the use of an earlier version of her work on women warriors, which was written more for popular consumption, without referencing her newer, more thorough and academic work.

"Women warriors and/or Valkyries and/or shield maidens (they are all often mixed up) are not just 'mythological phenomena' as stated by the authors, but relate to a whole complex of ideas that pervade literature, mythology and ideology, without necessarily providing any direct evidence for women warriors in 'real life,'" Jesch wrote in her blog post.

Another issue is that many of these sites were excavated in the 1800s, so it can be difficult to determine which "bags of bones" belong to which burials, Jesch added.

Of course, men who are buried with similar warlike accoutrements are rarely thought to be anything other than warriors, Hedenstierna-Jonson said in an interview with Science magazine. What's more, few of the graves in Birka have skeletons that sustained sharp-force trauma, suggesting that some of the warriors in this trading town may have been warriors more in title than in practice, the researchers wrote.

Either way, the researchers call for using the same standard of evidence with both male and female graves.

"Do weapons necessarily determine a warrior? The interpretation of grave goods is not straightforward, but it must be stressed that the interpretation should be made in a similar manner regardless of the biological sex of the interred individual," the researchers wrote in the paper.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus