Vikings Wintered and Planned Raids at 9th-Century English Site

A spot in England where thousands of Viking warriors and their families spent their winter months was bigger than most contemporary English towns.

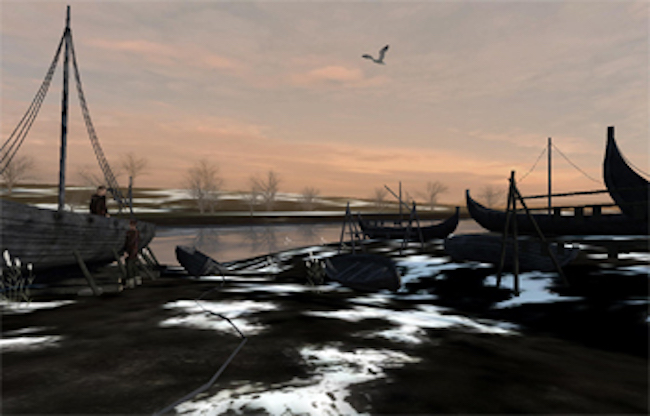

The camp, positioned near Torksey along the River Trent in Lincolnshire, was a major base for Viking raiders in the late ninth century. Archaeologists first found hints of the camp in the 1970s, but recently published for the first time a detailed description of the site's boundaries and artifacts in The Antiquaries Journal. Now, the researchers are unveiling a new virtual reality experience designed to put modern-day people inside a re-creation of the Torksey winter camp. The VR experience opened on May 19 at the Yorkshire Museum. [7 Secrets of Viking Seamen]

"These extraordinary images offer a fascinating snapshot of life at a time of great upheaval in Britain," University of York archaeologist Julian Richards said in a statement.

Winter with the Vikings

Up until the late 800s, Vikings frequently raided monasteries along the English coast in the warmer months and headed back to Scandinavia in the winter, Richards said. In 865, the Vikings sent their largest force ever to England — and decided to stay. Over the next decade, the Vikings switched their strategy from lightning raids to permanent takeovers of land and resources, Richards and his colleagues reported in The Antiquaries Journal in December 2016.

Historical sources reported that the Vikings made camp at Torksey between 872 and 873. Excavations there done between the 1970s and 1990s revealed a deep ditch that would have been part of this camp, but only since 2011 have archaeologists systematically excavated and discovered the camp's true size and scope. The site stretches 136 acres (55 hectares), and is bounded by wet, marshy land that would have provided a natural defense, Richards said. The camp was on elevated land, which also would have made it an appealing military location, Richards and his colleagues wrote.

Thousands of coins and other pieces of metal have been found at the campsite, including copper alloy made of lead, silver, gold and iron. More than 280 lead game pieces have been found, hinting at how the warriors passed the long, chilly off-season, the researchers said.

Winter's work

The overwintering Vikings also engaged in metalwork and the repair of ships, archaeologists have found. Researchers have discovered coins from as far away as the Middle East, transported along Viking trade routes. Archaeologists have also uncovered hundreds of pieces of hacked-up metals, which were probably awaiting their turn to be melted down, the researchers have said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Needles, spindles and awls hint at textile work such as the repair of ship sails and tents, which made up the main shelter for the Viking horde. Women may have been the textile workers of the camp, the researchers wrote.

Archaeologists have found some human remains at the camp, but the bones are too fragmentary to identify more than two bodies definitively (both men under the age of 35), researchers said. A separate fragment of skull bears the marks of a sharp implement, suggesting a violent death.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus