Here's Why 'Homemade Slime' Can Be Bad for Kids

It sounds like a fun science project, but making "slime" at home can hurt kids.

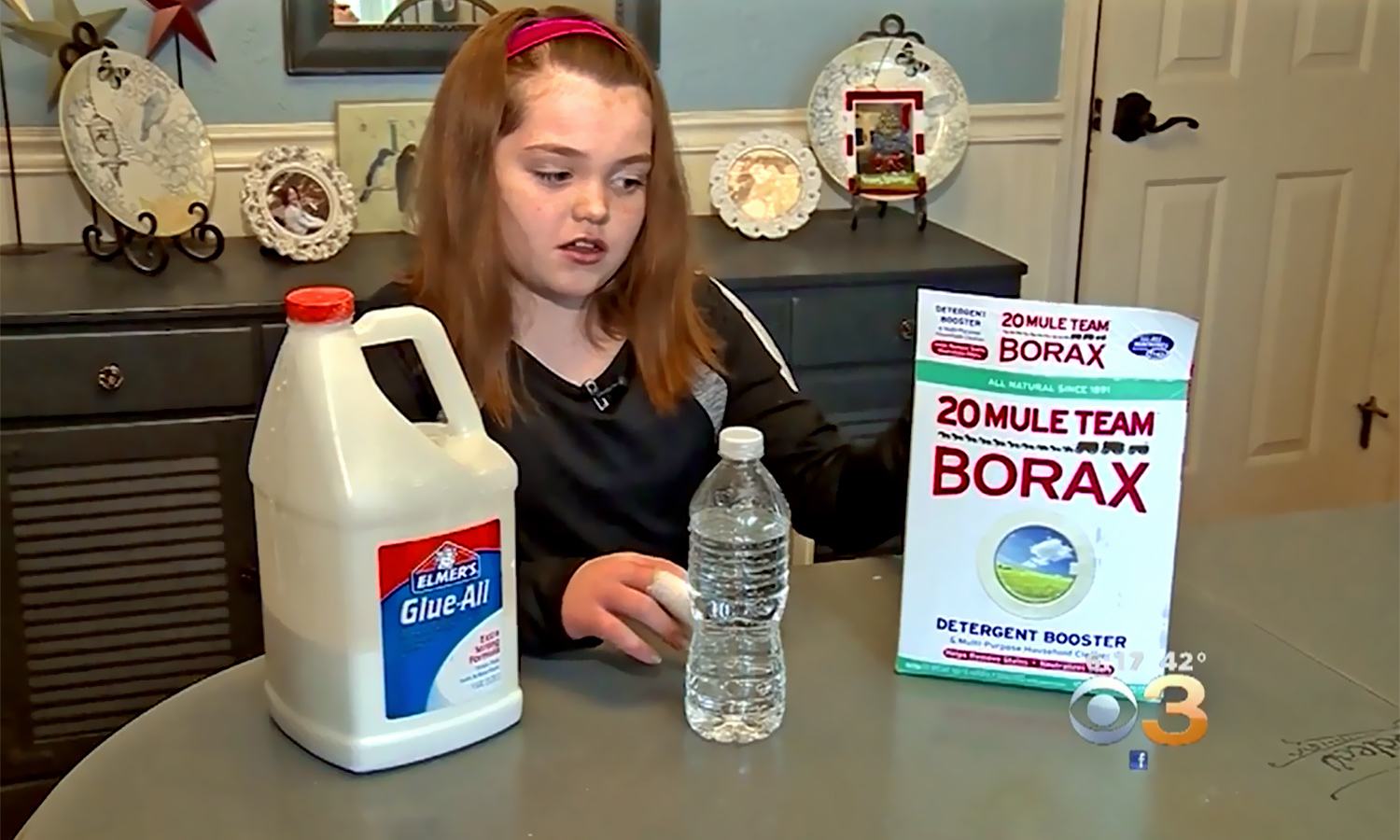

Kathleen Quinn, an 11-year-old in Massachusetts, started to feel tingling and burning in her hands after she made "slime" from a mixture of glue, water and borax, CBS News reported March 27.

Kathleen told her parents that her hands hurt, and when her mother, Siobhan Quinn, looked, she saw that her daughter's hands were covered in blisters, according to CBS. The girl was taken to the emergency room, where doctors treated her for second- and third-degree chemical burns, CBS News reported. [9 Weird Ways Kids Can Get Hurt]

Homemade "slime" has been increasing in popularity. So how does the concoction burn the skin?

The culprit is borax, or sodium borate. Borax is a mineral and is sold as a cleaning product.

Borax is a mild irritant, so it usually doesn't cause such deep chemical burns, said Dr. Michael Cooper, director of the Regional Burn Center at Staten Island University Hospital in New York. Cooper was not involved in the girl's case.

However, there are three factors that determine the severity of a burn, Cooper told Live Science. These factors apply to both chemical burns and burns from heat, Cooper said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

First, there's the length of time that a person is in contact with the chemical or the source of heat, Cooper said. The longer the person is exposed to the chemical or heat, the more severe the burn will be, he said.

Second, there's the strength of the chemical or the heat, he said.

Finally, the thickness of the skin also plays a role, and children have thinner skin, Cooper said.

In this case, the girl had relatively thin skin, and she was playing with the slime for a long time; those factors likely played a role in the severity of her burns, he said. It's also possible that the borax in the "slime" was pretty concentrated, which would have made it stronger than it would have been if it had been diluted with more water, Cooper added.

A chemical burn occurs when a chemical causes damage to the skin, Cooper said. Until the chemical is washed off, it will continue to cause damage, he said.

Second- and third-degree burns

If a burn damages only the top layer of the skin, called the epidermis, it's considered a first-degree burn, Cooper said. First-degree burns will turn red, but no blisters form, he said.

But Kathleen had second- and third-degree burns, which are more serious. Second-degree burns occur when the damage extends beneath the top layer of the skin, down into the layer called the dermis, Cooper said. In a second-degree burn, blisters form, he said. Blisters form because the top layer of skin becomes so damaged that it dies, and in turn, the body sends in fluid to lift the dead skin away from the healthy skin below, he said.

These burns can take several weeks to heal, Cooper said. During the healing process, people are recommended to gently wash the burn twice a day and cover it with an antibiotic ointment to fight infections, he said. The burn should also be protected with gauze, and sometimes, a person may have trouble moving his or her hand after recovering from a hand burn, Cooper added. The skin or muscle may be stiff from the healing process, and physical therapy may be needed, he said.

Third-degree burns occur when the damage from a burn reaches the tissues beneath both the epidermis and the dermis, Cooper said; these tissues include fat, muscle and tendon. Third-degree burns usually don't have blisters; rather, the skin has a white and leathery appearance, he said.

Third-degree burns can take several months to heal, and sometimes surgery is needed, Cooper said. During surgery, doctors perform a skin graft: they remove the damaged skin and tissue, and replace them with healthy skin and tissue from another part of the body, he said.

Originally published on Live Science.