Why Are Pandas Black and White?

The giant panda's distinctive black-and-white fur makes it one of the most recognizable animals on the planet. But why does it have this unique coloring?

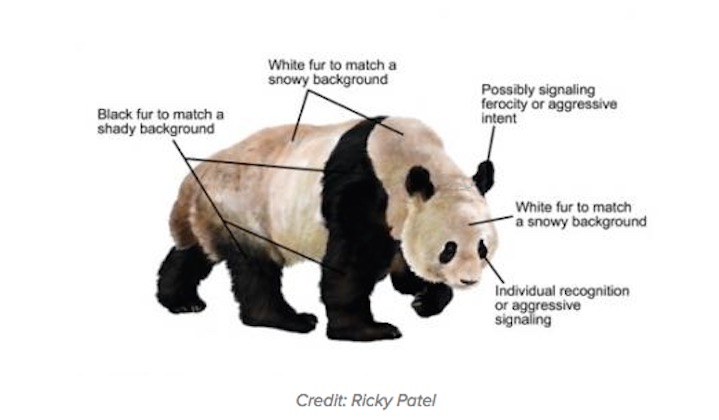

To hide from predators, both in the snow and in the shadows, scientists now say. Moreover, the large black circles around a panda's eyes may help other pandas recognize it, the researchers said.

"Understanding why the giant panda has such striking coloration has been a long-standing problem in biology that has been difficult to tackle because virtually no other mammal has this appearance, making analogies difficult," study lead author Tim Caro, a professor in the Department of Wildlife, Fish & Conservation Biology at the University of California, Davis, said in a statement.

To investigate, Caro and his colleagues looked at photos of pandas and 195 other carnivore species, including 39 subspecies of bear. Then, they noted the coloring on each region of those animals' bodies, and compared them with regions of the panda's body. [Cute Alert! Adorable Photos of Giant Panda Triplets]

"The breakthrough in the study was treating each part of the body as an independent area," Caro said.

The research team tried to match the dark-colored furry areas to different ecological and behavioral variables to figure out their purpose.

After going through many comparisons, the researchers determined that the white parts of the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) — its face, neck, belly and rump — help it hide in the snow. In contrast, its black arms and legs help it hide in the shadows, they said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The panda's white-and-black coloring didn't appear to be involved in temperature regulation or disruptive coloration, a type of camouflage in which an animal's markings don't coincide with the shape of its body. Nor did they find evidence that the dark circles around a panda's eyes helped to reduce glare.

It's possible that the panda's coloration is a result of its restricted diet. Pandas are known for eating bamboo almost exclusively. However, they don't have the gut bacteria to efficiently digest the tough plant, a 2015 study in the journal mBio found. Rather, pandas have gut bacteria reminiscent of their carnivorous bear ancestors.

Because pandas get such little nutrition and calories from chomping on bamboo, they can't store enough fat to go into hibernation during the winter, Caro and his colleagues said. So, pandas must stay active year-round, wandering long distances and across different types of habitats — from snowy mountains to tropical forests — to find more bamboo.

"We propose that as the giant panda is unable to molt sufficiently rapidly to match each background … it has evolved a compromise white and black pelage [fur]," the researchers wrote in the study, which was published online Feb. 28 in the journal Behavioral Ecology.

However, they said that the black markings on the panda's head are not used to hide from predators, but rather to communicate. The bears' black ears may help it express aggression as a warning to predators, Caro said. What's more, its dark eye patches may help pandas recognize each other, or signal hostility toward panda competitors, he said.

"This really was a Herculean effort by our team, finding and scoring thousands of images and scoring more than 10 areas per picture from over 20 possible colors," study co-author Ted Stankowich, an assistant professor of biology at California State University, Long Beach, said in the statement. "Sometimes it takes hundreds of hours of hard work to answer what seems like the simplest of questions: Why is the panda black and white?"

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.