Earth's Outer Shell: Was It Once Solid?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

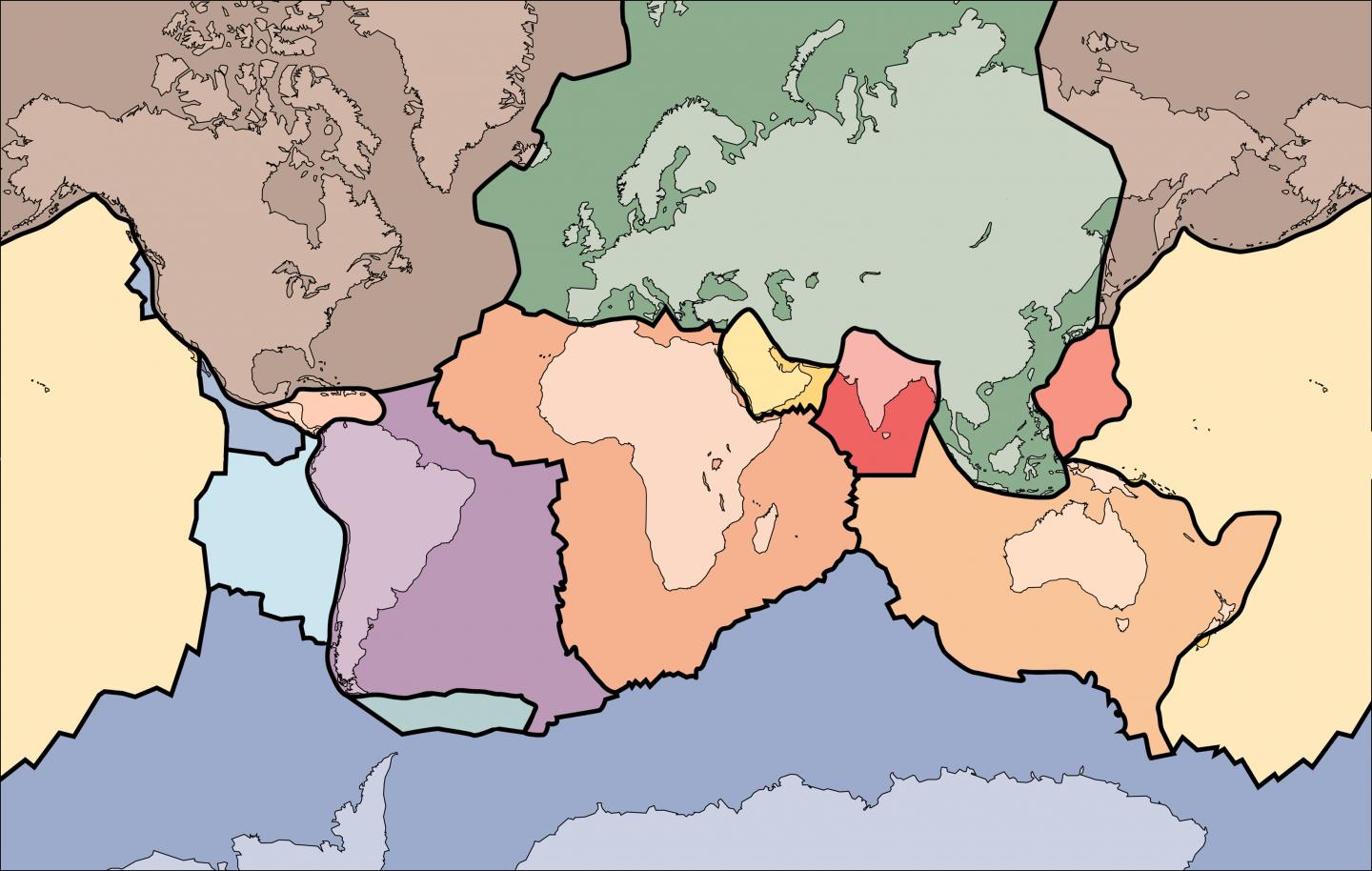

Earth's outer layer may have once been a solid shell before it was broken up into huge tectonic plates that move around and trigger extreme events like earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, scientists have found.

The history of Earth's outer shell has long been the subject of debate in the scientific community. Some scientists held a theory, known as uniformitarianism, that tectonic plates began early in the planet's history. Others, however, theorized that a solid shell originally covered Earth before it eventually fractured into the tectonic plates that are seen today.

Now, a team of scientists has found that the solid-shell model is the most likely explanation of how Earth's outer layer began. [50 Interesting Facts About Earth]

The new study finds support for the idea that the Earth's crust as "a 'stagnant lid' forming the planet's outer shell early in Earth's history" is a likely model, study co-author Michael Brown, a professor of geology at the University of Maryland, said in a statement.

To investigate the history of Earth's outer shell, Brown and his colleagues studied the planet's ancient rocks, specifically from a large area of ancient crust in western Australia. These rocks range from 2.5 billion to 3.5 billion years old (the Earth is about 4.6 billion years old). The researchers also studied rocks related to volcanic activity, which occurs at the borders of tectonic plates as they interact with one another.

The ancient crust's Pilbara granite rocks have a chemical composition similar to Coucal basalt rocks in the region, which are produced during volcanic activity or from molten basalt erupting on the ocean floor, the researchers found. The scientists looked into whether the ancient basalt could have created the granite without a volcanic source, therefore forming the crust without plate tectonic activity.

Using the Coucal basalts and Pilbara granites from the ancient crust, the scientists created experimental models, which they used to replicate how the Earth's outer layer could have formed without plate tectonics.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Based on the rocks' phase equilibria — which describes the rocks' behavior under different temperatures and pressure conditions — the researchers found that the basalts could have formed the Pilbara granites in a so-called "stagnant lid" scenario. The scientists found that the pressure and temperature of a single shell covering the planet would have stimulated the melting of basalts to form granites, according to the study.

"We conclude that a multi-stage process produced Earth's first continents in a 'stagnant lid' scenario before plate tectonics began," Brown said.

The research is detailed in a study published online today (Feb. 27) in the journal Nature.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus