Ancient 'Naked' Worm Did a Little Dance to Catch Seafood

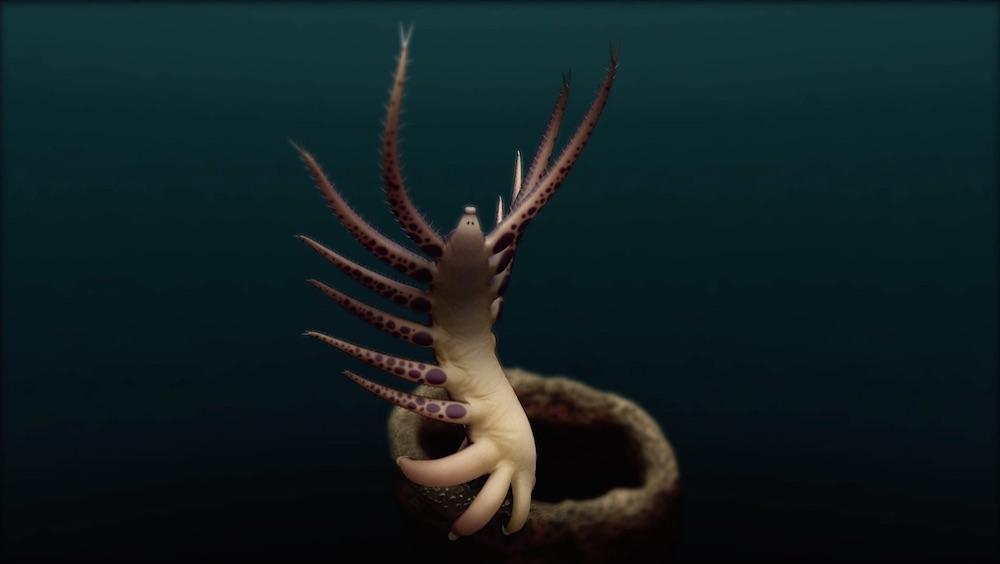

About 500 million years ago, a squishy, thumb-size sea creature did a little dance — waving its upper limbs around in the ocean in a never-ending attempt to ensnarl some tasty morsels floating by.

Researchers found the remains of this newly identified critter in the Burgess Shale deposit, a world-famous area in the Canadian Rockies that's brimming with animal fossils from the Cambrian Period (540 million to 490 million years ago).

"The Burgess Shale is certainly no stranger of already bizarre-looking creatures, but this new species is certainly one of the oddest," said study lead researcher Jean-Bernard Caron, the senior curator of invertebrate paleontology at the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada. [See Photos of the Weird, Thumb-Size Sea Creature]

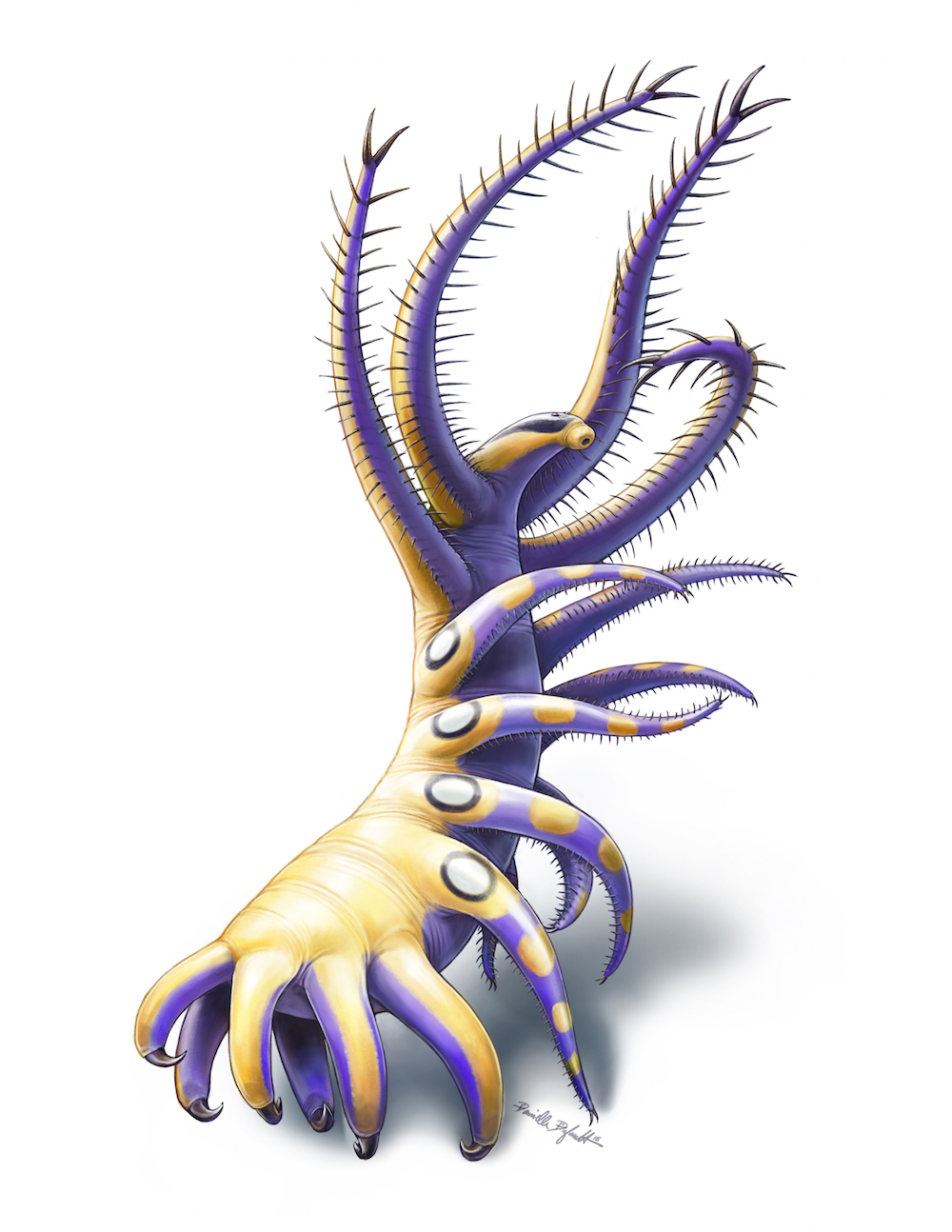

The newfound critter had nine pairs of limbs attached to its stubby "soft" body, Caron said.

"At first sight, the [upper] limbs look like combs," with spines coming off of them. However, its last three pairs of limbs look completely different: They appear stout and close to one another, and rather than having comb-like spines, each had just a single claw at its tip, Caron said.

"The animal likely used its three pairs of posterior limbs to anchor itself on the sea bottom and its frontal most limbs to sieve food items from the water," Caron told Live Science in an email.

He added, "We can only speculate about its diet … [but] based on the distance between the spines along its limbs, usually around 0.3 millimeters [0.01 inches], this animal probably ate tiny creatures called zooplankton."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Its unique anatomy earned it the name Ovatiovermis cribratus: The genus name Ovatiovermis refers to its posture and appearance — that of a worm-like critter that stood in perpetual ovation, and the species name cribratus refers to the Latin word for "sieve," the researchers said.

Wormy creatures

O. cribratus is a type of lobopodian, an extinct group of worm-like animals with soft limbs that gave rise to the largest group of living animals: the arthropods (such as spiders, crabs and insects) and two smaller groups, the velvet worms (onychophores) and the water bears (tardigrades), the researchers said.

Lobopodians rarely fossilize because they were made of soft tissue, which degrades more easily than bone. The animals are known from only about 30 fossil species worldwide, making the new finding a momentous one, they said.

Many lobopodians were suspension feeders — that is, they sieved the water for plankton and other bits of food. The two newfound specimens — one collected in 1994 and the other in 2011 — show that lobopodians formed two separate groups, each with its own strategies for suspension feeding. The discoveries suggest that suspension feeding was widespread during the Cambrian, the researchers said.

Moreover, it shows that arthropods, tardigrades and onychophores "all share an ancestor that was sieving the water to feed itself," Caron said. [In Images: A Filter-Feeding Cambrian Creature]

However, unlike other lobopodians, O. cribratus was naked. It didn't have defensive armor, such as plates, to protect it from predators, the researchers noted. "It has a smooth skin, and this begs the question of how this animal was able to [de]fend itself against large predators, which we know, would have lived in the same environment," Caron said.

Perhaps O. cribratus camouflaged itself, or maybe it used some toxic substance to keep predators at bay, he said.

The findings were published online Tuesday (Jan. 31) in the journal BMC Evolutionary Biology.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.