Saber-Toothed Cat Had a Huge Skull, But a Puny Bite

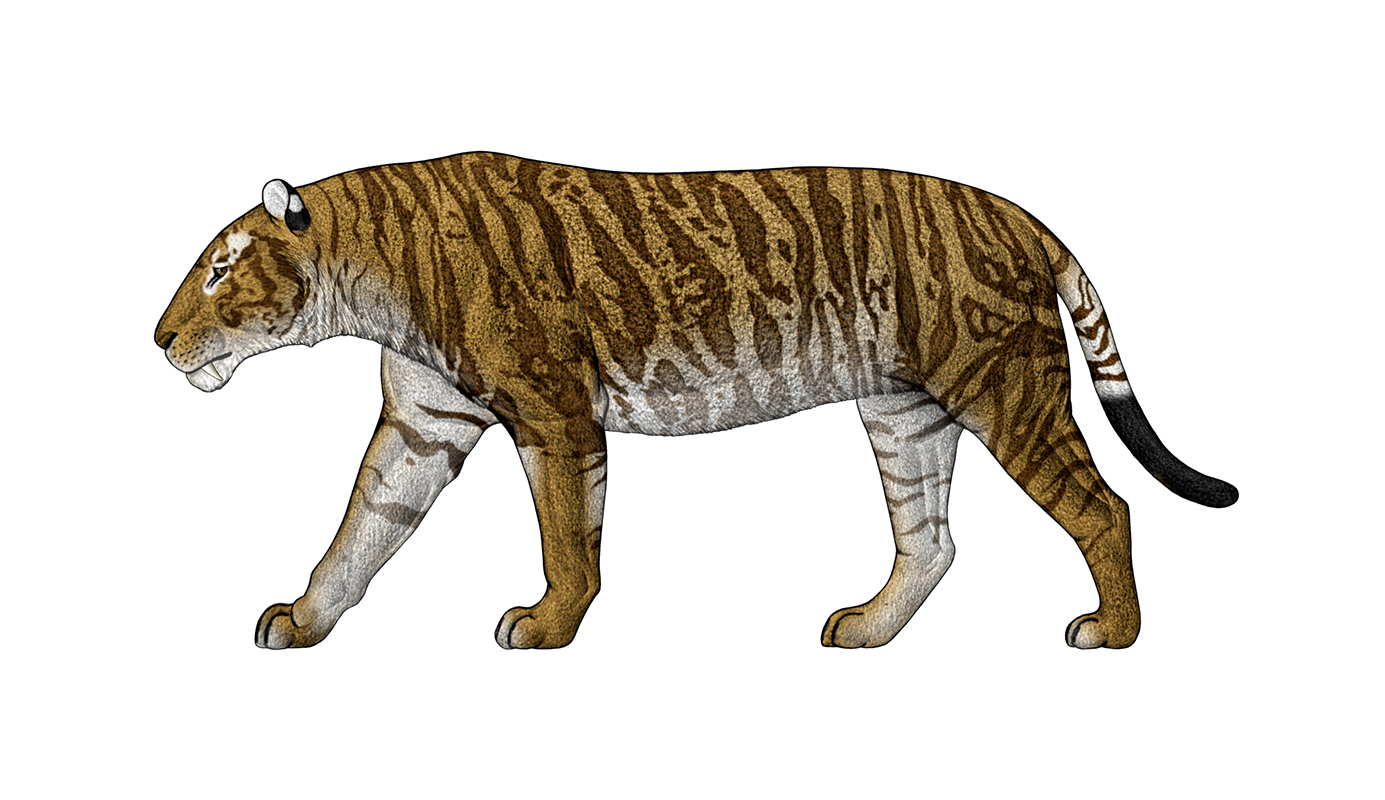

A newly described fossil skull from one of the largest of the saber-toothed cats, Machairodus horribilis, is the biggest saber-toothed skull ever found, and is helping scientists understand the diversity of killing techniques used by these extinct and fearsome predators.

The skull was excavated from the Longjiagou Basin in Gansu Province, China, but languished in storage for decades before researchers rediscovered it in a collection room and identified it in the new study.

And while M. horribilis may have had the biggest skull of the saber-toothed cats, it didn't necessarily have the biggest bite. When scientists analyzed the skull alongside its saber-toothed cousins, they estimated that it couldn't stretch its jaws as wide as some of the other extinct cats, which likely affected what type of prey it hunted and how it brought them down. [My, What Sharp Teeth! 12 Living and Extinct Saber-Toothed Animals]

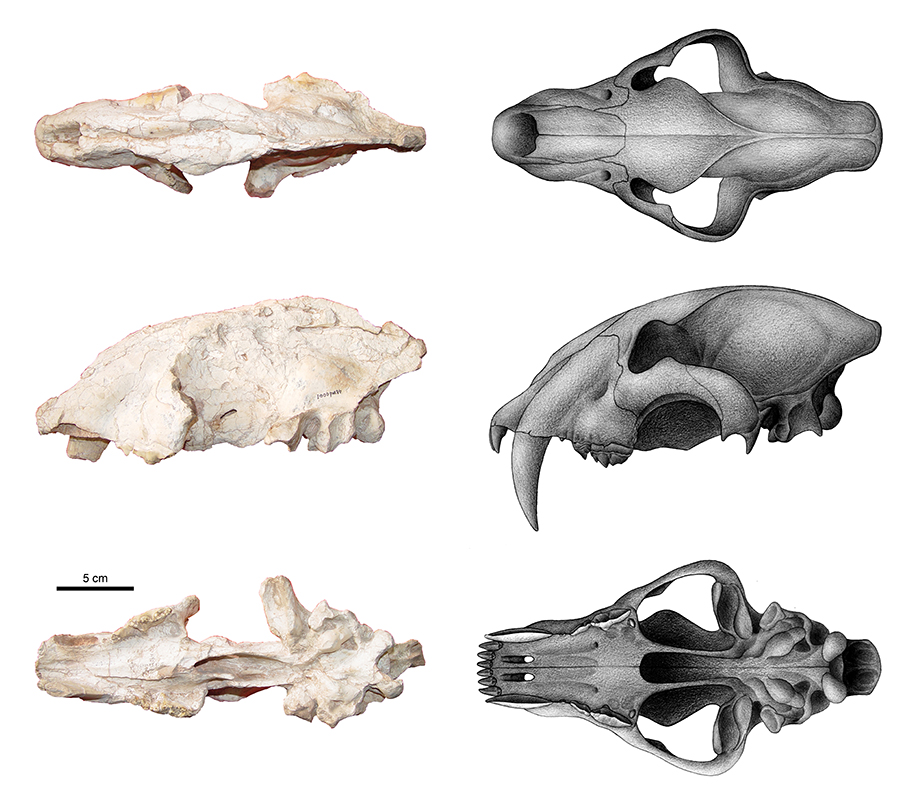

M. horribilis lived in the steppes and forests of northwestern China during the late Miocene epoch (11.6 million to 5.3 million years ago). The skull's upper surface measures 1.4 feet (415 millimeters) in length, and likely represents an adult male. Its incisors are arranged in a "gentle arch" and its signature upper canines are serrated on both edges, the study authors wrote.

Reconstructing an ancient bite

They noted that some of the fossil's features resembled those seen in primitive saber-toothed cats. But certain aspects of the skull shape were more like the skulls of modern lions and leopards, suggesting that M. horribilis may have had a range of motion in its jaw similar to large cats alive today.

Clues in both the shape and the surface texture of the fossil helped the scientists determine how the jaw may have moved in life, according to study co-author Z. Jack Tseng, a professor of pathology and anatomical sciences at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

"The surface of bones preserves ridges and bumps that indicate where muscles once attached, so paleontologists and anatomists can reconstruct the lines of action of the major muscle groups," Tseng told Live Science in an email.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The joints of the jaw — one on each side between the upper and lower jaws, and one down the middle between the two halves of the lower jaw — provide clues as to the mobility and range of motion possible in the animal’s bite."

But when it came to using its knife-like teeth for killing, M. horribilis was "a lightweight" compared with some other saber-tooths, Tseng added. It lacked the shallower jaw joints that allowed other cats' jaws to open wider — to enclose and rip out the throats of large prey. The jaws of M. horribilis just didn't stretch wide enough to do that, he said.

A burly predator

However, M. horribilis probably made up for that disadvantage with its bulk, Tseng said. The researchers estimated that it weighed nearly 900 pounds (400 kilograms), which would have given it a size and strength advantage over even large prey, which it probably killed by ripping open the throat "and causing massive blood loss," the study authors wrote.

"We found evidence of short-legged, probably slower-running horses in the same fossil assemblage," Tseng said. "Those horses are good candidates as this cat's main prey."

Their findings emphasize how even highly specialized adaptations — like extra-long canines — can be used by different species in different ways, even in closely related groups such as saber-toothed cats.

"Cats continue to surprise us," Tseng added. "We now think gigantism is one of those mechanisms for intermediate saber-tooths to get by as predators."

The findings were published online Oct. 25 in the journal Vertebrata PalAsiatica.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.