Cute Insect-Murdering Mammal Had Roots in Dinosaur Age

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Hundreds of years ago, hungry barn owls gobbled down small mammals called Nesophontes and regurgitated pellets of their remains. That mammal is now extinct, but a genetic analysis of the owl pellets reveals how it evolved from some of the earliest mammals approximately 70 million years ago.

Nesophontes was a genus of insect-eating critters that lived on the Caribbean islands, including Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico and the Cayman Islands. They were small, just between 0.3 and 4.4 ounces. (10 and 125 grams), and although their name hints at something sinister — it roughly translates to "island murder" in Greek — that's likely due to how many insects they devoured, the researchers said.

The Nesophontes genus includes eight species, the last of which went extinct about 500 years ago when the Europeans arrived in the Caribbean, accompanied by the invasive black rats (Rattus rattus) that lived on their boats, the researchers said. [Gallery: A View of Rat Island]

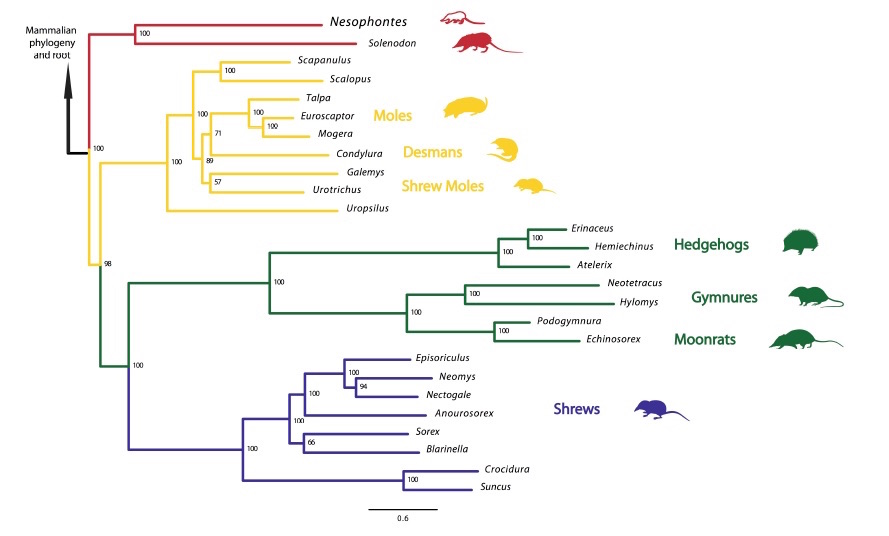

Even though members of the Nesophontes genus are now extinct, researchers have found specimens and determined that it was rather primitive looking for a mammal. But they weren't sure exactly how the animal was related to its closest insectivore relatives, including shrews, hedgehogs and moles.

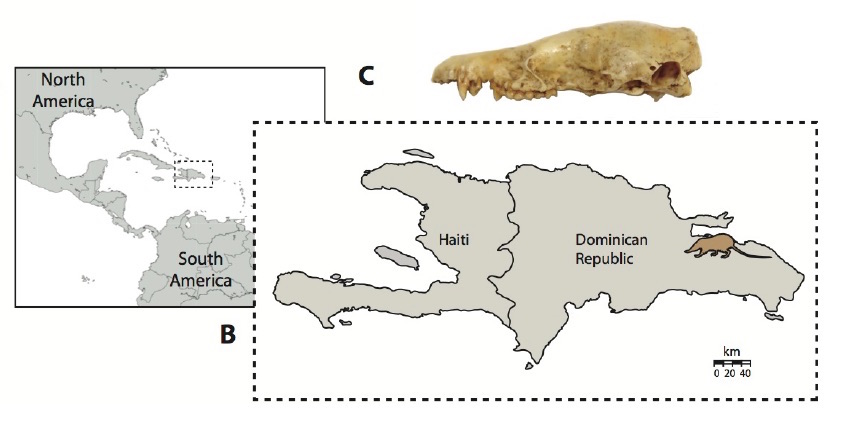

To investigate, they carefully examined tiny Nesophontes bones found in a 750-year-old barn owl pellet from the Dominican Republic. An ancient DNA analysis of the bones revealed that Nesophontes is a sister group to another Caribbean insectivore group, the solenodons, which are venomous and nocturnal burrowing mammals.

Extracting the DNA from the bones was difficult work, but new developments in ancient-DNA technology helped the researchers to get their results.

"Once we'd dealt with the tiny size of the bone samples, the highly degraded state of the DNA, and the lack of any similar genomes to compare to, the analysis was a piece of cake," study lead author Selina Brace, a scientist at the Natural History Museum in London, said in a statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They found that Nesophontes diverged from the solenodons about 57 million years ago. That's about 2 million years before the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, a period of rapid global climate change, the researchers said.

These temperature changes are "linked to major diversification and faunal [animal] turnover in other mammal groups," the researchers wrote in the study.

"Nesophontidae is thus an older distinct lineage than many extant [living] mammalian orders," they wrote.

The oldest true mammal is about 160 million years old, researchers told Live Science in 2011, and although Nesophontes' ancestor is slightly younger at 70 million years old, it still lived during the dinosaur age, the researchers said.

In addition, the northern Caribbean looked different during that time. It was made of volcanic islands rather than the current islands recognized today, the researchers said. They noted that islands such as these can help preserve unique animals, such as Nesophontes, whose demise can serve as a cautionary tale that people should be careful to limit the introduction of invasive species into fragile ecosystems.

"Nesophontes was just one of the dozens of mammals that went extinct in the Caribbean during recent times," said Professor Ian Barnes, a research leader at London's Natural History Museum.

The findings were published online today (Sept. 13) in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus