Cold-War-Era Toxic Waste Could Be Released by Greenland's Melting Ice

It may sound like a storyline straight out of a Godzilla movie, but researchers are warning that toxic waste from a long-abandoned Cold War-era camp could leach into nearby ecosystems as a result of warming temperatures in Greenland.

It was thought that the hazardous waste would stay buried and frozen forever beneath the Greenland Ice Sheet, but climate change is warming the Arctic and causing portions of the ice sheet to melt, the researchers reported in a new study.

"In the past, militaries, industry and even scientists have given little thought to the lasting impact of their activities, including dangerous waste left behind," Laurence Smith, a professor in the Department of Geography at the University of California, Los Angeles and author of "The World in 2050: Four Forces Shaping Civilization's Northern Future" (Dutton Adult, 2010), told Live Science in an email. "That attitude is changing but not gone, and this study shows how the activities of the past are with us still." [See Photos of the Cold War-Era Military Base]

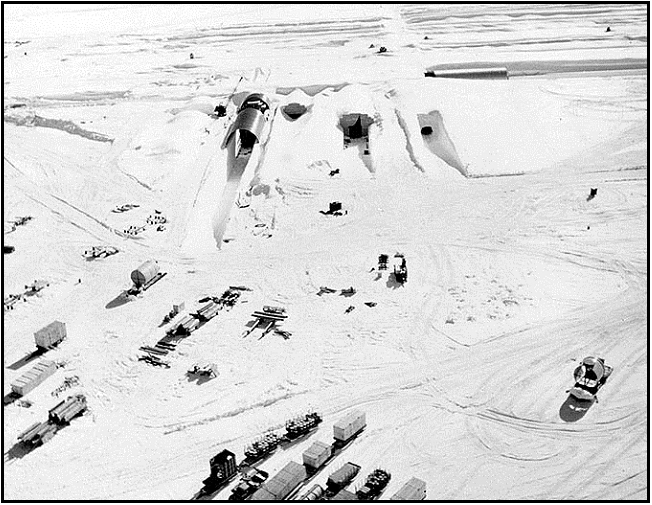

According to the new study, waste from the Cold War-era camp, known as Camp Century, covers 136 acres (0.55 square kilometers), or about the size of 100 football fields. This includes approximately 53,000 gallons (200,000 liters) of diesel fuel; building materials; and 63,000 gallons (240,000 liters) of wastewater, which includes a large amount of sewage.

"It became pretty obvious that none of these sites had received proper decommissioning," said study lead author William Colgan, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Space Science and Engineering at York University in Toronto. The base also likely contains a small amount of nuclear waste, but Colgan said this isn't as concerning as some of the other toxic materials.

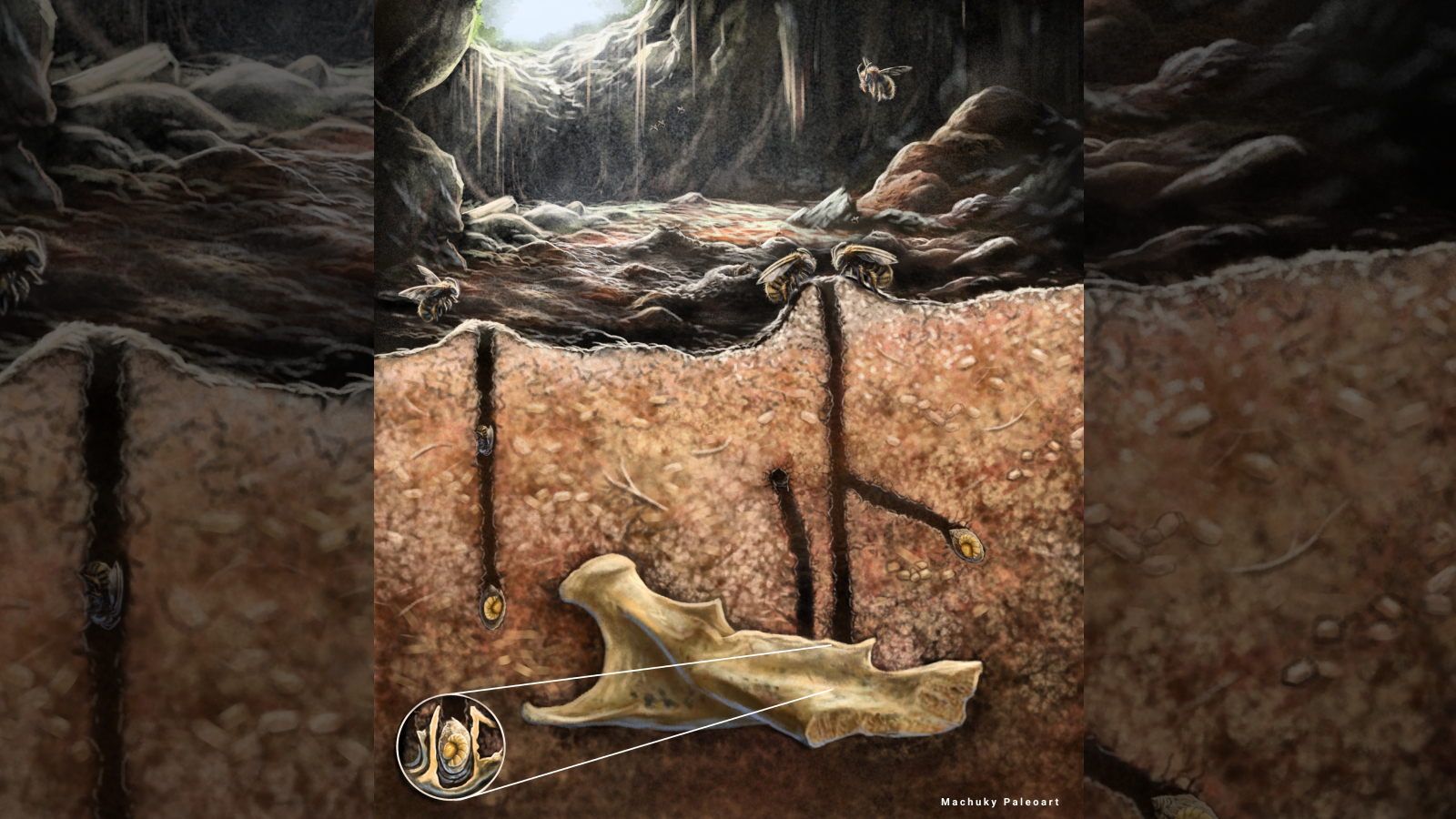

Perhaps most worrying is that the site contains polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), chemicals that were once widely used in electrical structures and equipment, the researchers said. In animal studies, these chemicals were shown to be harmful to the immune system, reproductive system, nervous system and endocrine system, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Similarly wide-ranging effects are likely in humans as well, and PCBs can increase the likelihood of various health problems, including cancer, EPA studies have shown.

Colgan and his colleagues warned that, if human-driven climate change continues on the present course, the ice covering the site could begin to melt in about 75 years. It would be much longer before the base itself would become exposed, but in the meantime, meltwater could move through the ice, saturating structures in the base and carrying toxic waste with it as it flows to the coast, they said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cold War history

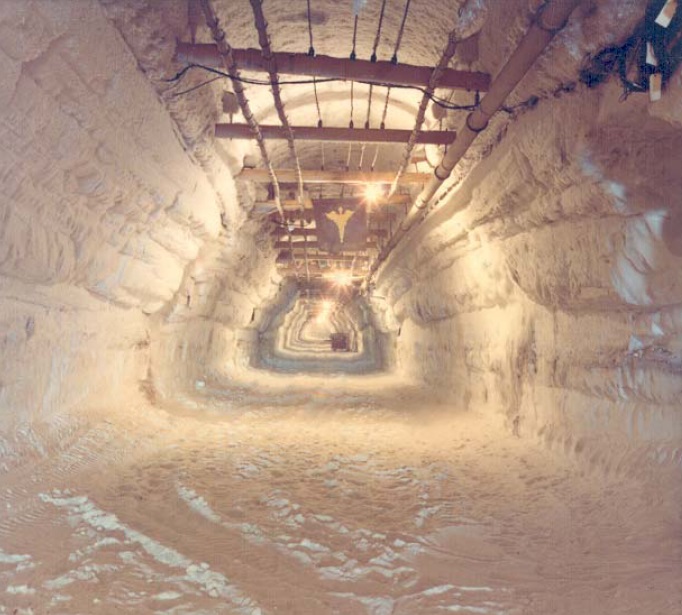

The new study details the history of Camp Century, a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers military base that was built in the Greenland Ice Sheet in 1959. The base, located 125 miles (200 kilometers) from Greenland's northwest coast, was called the "city under the ice," because the entire infrastructure was buried under more than 26 feet (8 meters) of ice to provide protection and camouflage. According to the researchers, Camp Century housed up to 200 soldiers and was powered by a portable nuclear reactor, which Colgan said was removed during decommissioning.

The area, though desolate, was strategic because the Artic provided the shortest route between the United States and the Soviet Union. Camp Century was one of many camps built under an agreement with Denmark to defend Greenland. [Flying Saucers to Mind Control: 7 Declassified Military & CIA Secrets]

Officially, the camp was used to conduct scientific research and test Arctic construction strategies. Unofficially, it was also a top-secret proof of concept for building nuclear missile launch sites in the ice. This program was known as Project Iceworm because it involved burrowing a 2,500-mile-long (4,000 km) tunnel through the ice, from which up to 600 ballistic missiles could be deployed. This tunnel was never actually built, but something akin to a prototype was created, in the form of a 1-mile-long (1.6 km) underground railway, the researchers said.

The project was not approved by the Danish government and was eventually rejected by the U.S. Department of Defense's Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1963. Camp Century was decommissioned in 1967.

Environmental effects

The possibility that these chemicals could leach out of the long-abandoned base is compounded by another problem: The Arctic already experiences a disproportionate burden from PCBs due to a phenomenon called the "grasshopper phenomenon," Colgan said. This occurs when pollutants are released and evaporate in warm areas and then are carried by winds to cold areas, where they settle back toward the surface. [6 Unexpected Effects of Climate Change]

And although the area surrounding Camp Century is desolate, Greenland's environment and the people who live off of it could suffer serious consequences, Colgan said.

"The Greenland ecosystem — the Arctic ecosystem, in general — is pretty fragile," Colgan said. "It's just clinging to life." Although the human population is relatively small, there are people in Greenland and nearby areas of the Arctic who hunt for their food, which means they could be exposed to these chemicals through food sources that are crucial to their way of life, he added.

Camp Century is a lesson in climate change that's been largely ignored for decades, according to the scientists. But although the issues at the base are only now being examined, Camp Century is already a well-known site of concern for climate scientists. In fact, it was the first place where an ice-core sample was taken from Greenland, in 1966, to monitor the effects of climate change, Colgan said.

"This work brings fresh attention to a chronic problem in the Arctic," Smith said. "The Arctic is a fascinating place where fast climate change, environmental sensitivity and geopolitics converge."

The findings were published online Aug. 4 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Original article on Live Science.