6 Unexpected Effects of Climate Change

Along with its anxiety-inducing effects, climate change also offers an interesting opportunity to consider fascinating, interconnected processes on Earth. The smallest to the largest components of the planet – from bacteria to volcanoes – all somehow feel the effects of a changing climate. Here are six of the most unexpected effects of global warming on Earth.

Desert bacteria dies

Desert soil may appear desolate and void of life, but it actually teems with bacteria. Bacterial colonies can grow so thick that they form sturdy layers called biocrusts that stabilize soil against erosion.

A study of these biocrusts across deserts in the United States showed that different types of desert bacteria thrive in different temperature regimes. Some prefer the sweltering heat of Arizona and New Mexico, while others fare better in the cooler climate of southern Oregon and Utah. As temperatures become more erratic with climate change, desert bacteria may struggle to adapt, leaving desert soil more prone to erosion.

Volcanic eruptions explode

As glacial meltwater floods into oceans and the global sea level rises with climate change, the distribution of weight on the Earth's crust will shift from land to sea.

This shift in weight distribution could cause volcanoes to erupt more often, some studies suggest. Evidence of this phenomenon has been detected in the rock record, with remnants of more abundant volcanic eruptions correlating with periods of glacial melt at several points in Earth history. Humans in the 21st century probably won't experience this shift, however, since this effect seems to lag by up to about 2,500 years.

Oceans darken

Climate change will increase precipitation in some regions of the world, resulting in stronger-flowing rivers. Stronger river currents stir up more silt and debris, which all eventually flows into the ocean and makes the ocean more opaque. Regions along the coast of Norway have already experienced increasingly darker and murkier ocean water with increased precipitation and snow melt in recent decades. Some researchers have speculated that the murkiness is responsible for changes in regional ecosystems, including a spike in jellyfish populations.

Allergies worsen

As climate change causes springtime to spring out earlier in the year, sneeze-inducing pollen will ride the airwaves that much earlier in the year as well. This will increase the overall pollen load each year, and could make people's allergies worse. Some temperature and precipitation models have shown that pollen levels could more than double by the year 2040.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

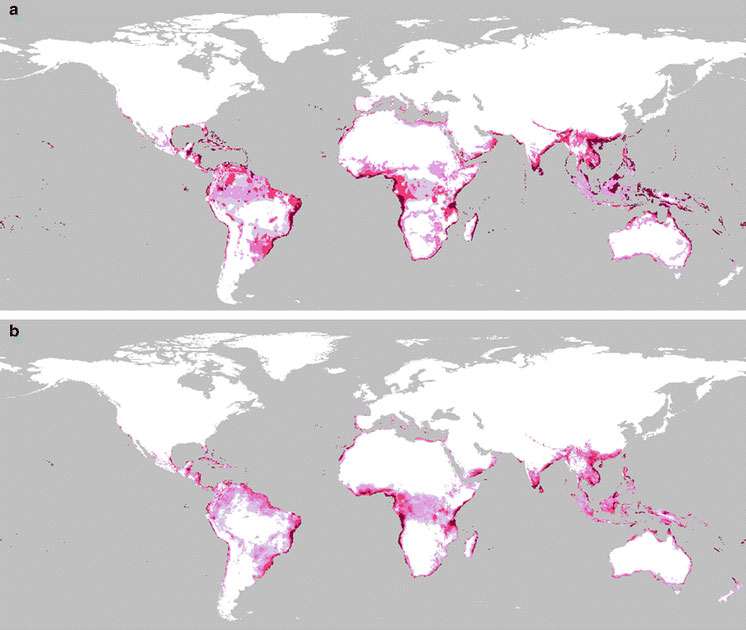

Ant invasions slow

Pheidole megacephala, also known as the big-headed ant, is one of the top 100 most invasive species on Earth. Hoards of these insects thrive in South America, Australia and Africa, and their voracious populations spread rapidly. As invasive animals, they steal habitat and resources from native species, disrupting regional ecosystems and jeopardizing biodiversity. They have even been known to hunt bird hatchlings.

Researchers have estimated that 18.5 percent of the land on Earth currently supports the big-headed ant. But as temperatures shift in the coming decades, the habitat range of these cold-blooded animals will likely shrink substantially. Some climate models suggest that the ant's range will decrease by one-fifth by the year 2080. How native insects will respond to these changes, however, remains unclear.

Sunlight floods polar seafloor

As sea ice melts, more sunlight will bathe shallow coastal regions around the poles. Seafloor communities of worms, sponges, and other invertebrates accustomed to existing in darkness will begin to experience longer periods of sunlight each summer. Recent research has shown that this shift could significantly alter these communities, by allowing seaweeds and other marine plant-life to smother invertebrates. This transition from invertebrate-dominated communities to algae-dominated communities has already been observed in pockets of both the Arctic and Antarctic coastlines, and could significantly decrease biodiversity in these regions.