11 Famous Places That Are Littered with Dead Bodies

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Memento mori

Who's afraid of a little memento mori? Most of the time, humans shove death out of sight, confining reminders of mortality to cemeteries and funerals. But at some famous places, the specter of death is all around.

Read on for some spots literally littered with corpses.

Pompeii

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79 wiped out many of the inhabitants of Pompeii in a flash of heat. Their bodies were rapidly covered with up to 20 feet (6 meters) of ash, which was falling at a rate of at least 6 inches (15 centimeters) per hour.

After the bodies decayed, they left bone-filled voids in the ash. One of the early excavators of Pompeii, Giuseppe Fiorelli, developed a technique of filling these voids with plaster and then excavating around them, leaving a cast of the bodies just as they were positioned when the victims died.

Those eerie casts are famous for the very human, alarmingly relatable suffering they reveal. Many also contain skeletal remains, trapped in thick plaster that makes imaging difficult. In 2015, though, researchers used multi-layer computed tomography (CT) to peer inside three of the casts, revealing bones and "perfect teeth," according to news reports.

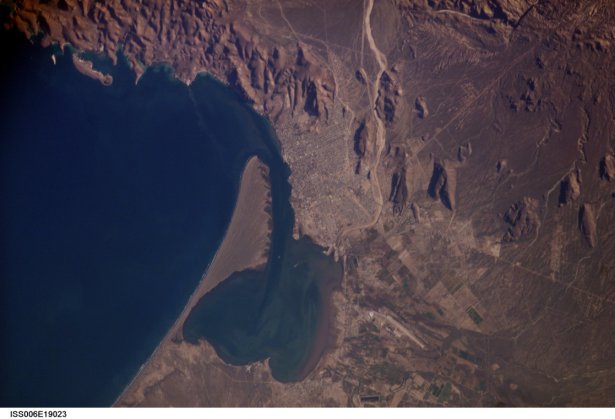

The Piled Bones of Baja

Strange burials dominate the archaeological site of El Conchalito on La Paz Bay (shown here) in the Mexican state of Baja California Sur. Ancient people lived at the site starting at least 2,300 years ago, and 57 of their dead have been found in shallow graves lined with seashells.

Some of the skeletal remains were found intact, laid to rest on their backs or curled on their sides. But a substantial number were discovered dismembered. For example, the body of one 30- to 35-year-old man was found with most of his spine, his hip and ribs detached from his neck and put in front of his face, wrote Alfonso Rosales-Lopez and colleagues in a 2007 article in the journal Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly. One of his arm bones had been shoved through his skull.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Apparently, the ancient people who lived at El Conchalito developed a tradition in which they buried their dead intact and later exhumed them and split the skeletons in half at the waist by twisting, pulling and cutting with stone tools. The lower half of the body was then put on top of the upper half, according to the PCAS Quarterly article. Usually the sectioning was quite neat, but sometimes the procedure failed and the bones ended up in a messy pile. The tradition may have been related to the belief that without this postmortem process, the dead might come back to life, Lopez and colleagues wrote.

Skeleton Lake

In 1942, a forest ranger in Uttarakhand, India, stumbled upon an eerie tableau: a jewel-like glacial lake filled with human skeletal remains.

Roopkund Lake sits 16,499 feet (5,028 m) above sea level in the Himalayas. It takes a days-long trek to reach the spot, which makes the presence of hundreds of skeletons all the more mysterious. At first, most people theorized that the dead were modern people, but in 2004, researchers dated the bones back to about A.D. 850, according to Atlas Obscura. Strangely, death seems to have come from blows to the head and shoulders, but the wounds didn't look like they were made by weapons. Most likely, the researchers concluded, the dead were a group of travelers caught in a violent hailstorm, pummeled to death by balls of ice up to 9 inches (23 centimeters) in diameter.

Mount Everest

The highest mountain on land has claimed many lives. Cold temperatures, high elevations, crevasses and avalanches make Everest a dangerous place to be. These same factors also make it dangerous to recover the bodies of people who have died on their journeys to the summit.

Around 200 bodies rest on the 29,029-foot (8,848 meters) peak, according to a 2015 BBC investigation. Some are out in the open along popular routes to the summit. One, dubbed "Green Boots," was even considered a sort of local landmark, easily identifiable by his neon climbing boots and resting on the mountain's northwest ridge. According to the 2015 BBC investigation, the body disappeared from the spot it had been for almost 20 years in 2014, as did perhaps a half-dozen others along the summit stretch. It's possible the bodies were moved or covered with stones by one of the Chinese associations that manages the north slope of the mountain.

Smoked Mummies of Papua New Guinea

The dead aren't tucked away in the village of Koke, which sits in Papua New Guinea's Aseki region. Here, the traditional method of dealing with the dead was to smoke the bodies over low heat for 30 days and then slather them with red clay. The process deters bacteria and decay, preserving the corpses for generations. The mummies were then propped on a cliff above the village. In 2008, western anthropologists even helped local villagers restore one of the corpses, a chief who died in the 1950s. Traditional belief among the Anga tribe, which developed these rituals, holds that spirits may roam and cause trouble if their bodies aren't preserved. The living also talk to the dead and seek their advice.

Paris Catacombs

No discussion of human remains would be complete without a peek into the famous catacombs of Paris, where the bones of millions are stacked in labyrinthine tunnels.

Officials began to transfer bones from overcrowded city cemeteries in the 1700s, a process that continued until 1859. Some victims of massacres and the guillotine during the French Revolution even got direct burials in the catacombs, according to the Carnavalet Museum in Paris, the museum that now manages the tunnels. Among the famous figures interred somewhere in the catacombs is Maximilien Robespierre, the French politician instrumental in the revolution who was executed by guillotine in 1794.

Bone Church

Macabre doesn't begin to describe the Capuchin Crypt in Rome, where the bones of approximately 3,700 monks decorate five bizarre chambers. One room depicts Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead, in skeleton form. Another uses predominantly pelvises for décor. There's a room dedicated to skulls and another decorated with thigh and arm bones. The final chamber shows a skeleton holding a scythe and a scale, representing death and divine judgment.

The Capuchin friars who created this walk-in memento mori began the project in the 1600s with bones of brothers who had died as early as 1528. They created something of an assembly line of death, interring the recently deceased in a crypt and removing the longest-dead for incorporation into the church's decoration. The youngest bones date to the late 1800s.

A Macabre Memorial

For sheer numbers, though, the Capuchin Crypt can't compete with St. Bartholomew's Church in Czermna in Poland. Better known as the "skull chapel," this 18th-century building looks modest on the outside. Inside and beneath, though, are the bones of at least 24,000 people who died in wars and plagues. Conflicts dating back to the 1600s provided the raw material: The Thirty Years' War, the First, Second and Third Silesian Wars, along with local skirmishes and cholera epidemics. [10 Tales from the Crypt and Beyond]

According to Atlas Obscura, about 3,000 skulls-and-crossbones decorate the chapel, while the rest of the dead — disinterred from mass graves — are stacked in a crypt below the church floor.

Cliffside Coffins

In mountainous southern China, the Bo people developed an interesting way to keep their dead out of the mouths of scavengers: They hung their coffins from cliffs.

Up to about 400 years ago, this group carved coffins from single logs and placed them on rock ledges or stakes pounded into vertical rock faces. The Hanging Coffins are mostly found in Gongxian, in Sichuan province, but archaeologists have also discovered clusters in other parts of southern China. In 2015, for example, researchers announced that they'd found 131 hanging coffins in Hubei province, dating back 1,200 years.

Little is known about the Bo people, but the reports filtering down through the centuries are strange. According to a 1991 article in Archaeology Archive by the then-president of the China Exploration and Research Society, it was Bo custom to toughen up by wearing heavy garments in summer and thin clothes in winter. (Shown here, the hanging coffins of Sagada in the Philippines.)

Ancient Battle Zone

The bucolic Tollense river valley in northeastern Germany hides the remnants of a bloody past. Bronze Age skulls occasionally turned up in the sediments of the valley, but in 1996 an amateur archaeologist discovered something surprising: an arm bone with a flint arrow piercing it.

Since then, archaeologists have discovered more beat-up bones, including fractured skulls and lots of weaponry: clubs, flint points and even a wooden weapon that looked a bit like a croquet mallet. So far, the remains of 100 people, mostly young men, have been found, researchers reported in June 2011 in the journal Antiquity.

The carnage points to a major battle fought sometime around 1230 B.C., the researchers wrote. The scale of the battle, with at least 100 killed, was larger than any other warfare known from this time and place. Damage to the front of skulls hints at fighting done face-to-face. Many of the dead had healed wounds, suggesting that they were professional warriors. No one knows, however, what conflict led to the bones of these men being scattered along the Tollense.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus