Armor Up! Water Fleas Grow Helmets and Spines for Battle

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

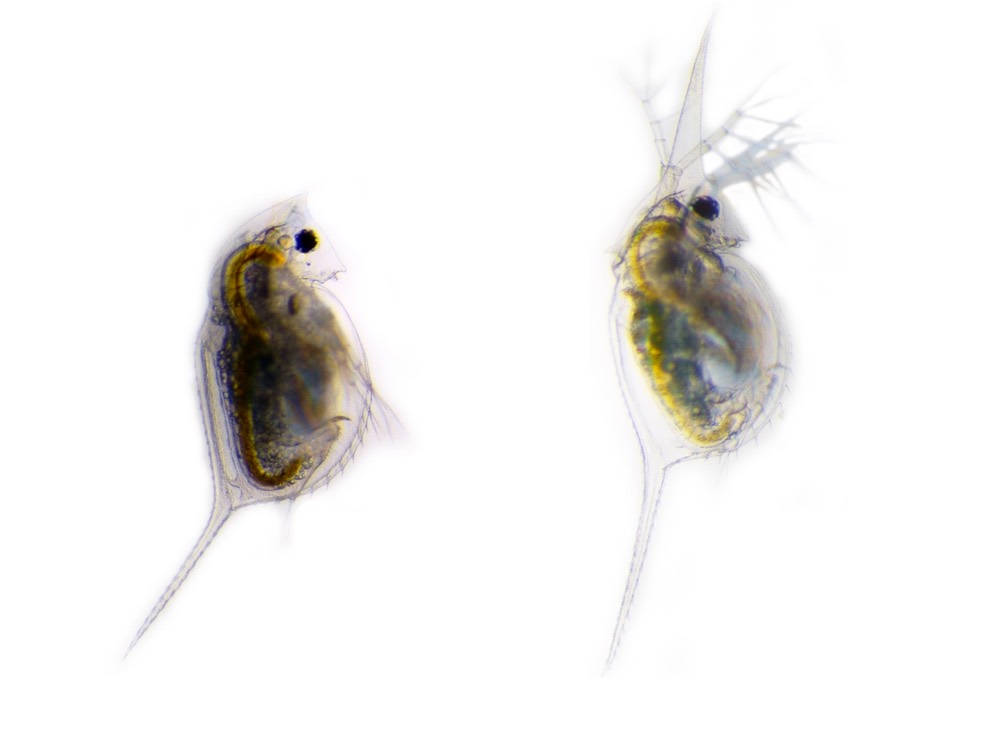

Water fleas prepare for battle by growing armor that's customized to specific enemies, new research finds.

Tiny Daphnia species develop impressive protective structures as they mature, including pointy tail spines and tough helmets. Now, researcher Linda Weiss of Ruhr-University Bochum in Germany and her colleagues have found the neurotransmitters that help water fleas customize their bodies in response to the chemical cues in their watery environments.

"Dopamine, in particular, appears to code neuronal signals into endocrine [hormone] signals," Weiss said in a statement.

Daphnia is a genus comprising many species of the tiny crustaceans known as water fleas. Most are less than 0.2 inches (5 millimeters) long, and look much like translucent versions of the land-based fleas that give them their nickname. [Tiny Grandeur: Stunning Photos of the Very Small]

When juvenile Daphnia molt and develop a mature exoskeleton, they mold their bodies based on the chemicals they encounter in the water. The water fleas use appendages called antennules to detect scents and chemicals left by predators (fish, for example, or the upside-down swimming insects called backswimmers). They then develop armor defenses in response to the threats they expect to face.

"These defenses are speculated to act like an anti-lock key system, which means that they somehow interfere with the predator's feeding apparatus," Weiss said. "Many freshwater fish can only eat small prey. So, for example, Daphnia lumholtzi grows head and tail spines to make eating them more difficult."

Weiss and her colleagues have found the intermediary steps that make this transformation occur. The antennules create brain signals when they detect chemical cues, which in turn cause the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine. Dopamine, in turn, cues the release of juvenile hormones that promote growth in particular body regions.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The same juvenile hormones promote growth in many other arthropods, Weiss said, which suggests that this developmental pathway is a widely shared way for crustaceans and insects to respond to environmental conditions.

Little Daphnia can also act as a canary in a coal mine for water quality, Weiss said. Understanding how water fleas change in response to chemical cues "will help in our understanding of the composition and population dynamics of freshwater ecosystems," Weiss said. "As freshwater is one of the most important resources on Earth, it is important to study the communities it holds."

Weiss will present her findings, which have yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, today (July 6) at the annual meeting for the Society for Experimental Biology in Brighton, England.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus