Butchered Bear Pushes Back Human Arrival on Ireland

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

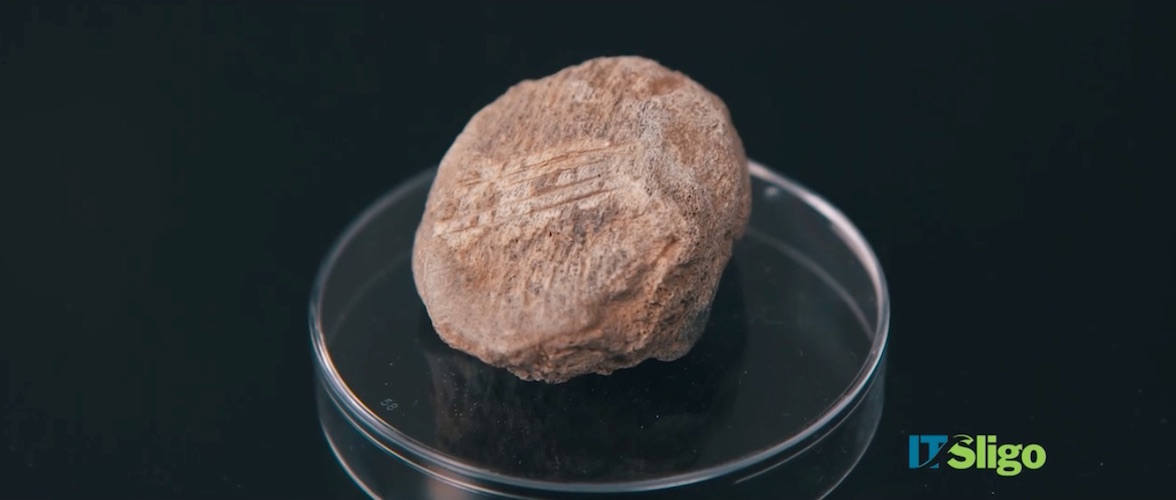

The slashed kneecap of a bear found deep inside a prehistoric cave suggests human hunters lived in Ireland earlier than had been previously thought, a new study finds.

Until now, the earliest evidence of humans in Ireland dated to the Mesolithic period, about 10,000 years ago. But new analyses of the bear's kneecap push back that date by 2,500 years, and shine a light on what animals these prehistoric people ate and what butchery techniques they used.

Researchers found the kneecap in Ireland's Alice and Gwendoline Cave, in County Clare, in 1903. They noted that the bone had knife marks on it, but no one gave the artifact a second look for about 100 years. [Emerald Isle: A Photo Tour of Ireland]

Then, in 2010 and 2011, Ruth Carden, an animal osteologist at the National Museum of Ireland, began going through the cave's many bone artifacts. She had two independent experts radiocarbon-date the kneecap and another three specialists examine the cut marks (to ensure that these marks were made shortly after the bear died).

The two radiocarbon-dating experts agreed that the bone was about 12,500 years old. Moreover, the other specialists confirmed that the cuts were made on fresh bone, Carden said.

The finding shows that people likely lived in Ireland during the Paleolithic period, which is also known as the Old Stone Age.

"Archaeologists have been searching for the Irish Paleolithic since the 19th century, and now, finally, the first piece of the jigsaw has been revealed," Marion Dowd, an archaeologist at the Institute of Technology, Sligo, in Ireland, said in a statement. "This find adds a new chapter to the human history of Ireland."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The results of the radiocarbon dating surprised the researchers, they said. This technique measures the amount of carbon-14 left in an organism that was once alive. (Carbon-14 is an isotope, or variant, of carbon, meaning it has a different number of neutrons in its nucleus than the more common Carbon-12.) This method works on remains that are up to 50,000 years old, so the brown bear's patella fit within these parameters.

"When a Paleolithic date was returned, it came as quite a shock," Dowd said. "Here we had evidence of someone butchering a brown bear carcass and cutting through the knee probably to extract the tendons. Yes, we expected a prehistoric date, but the Paleolithic result took us completely by surprise."

However, whoever cut the kneecap probably wasn't that experienced, the researchers said. A number of score marks are visible, showing that multiple slashes — likely made with a long flint blade — were needed to get the job done, Dowd said.

She added that the scientists plan to examine more bones found from the 1903 cave excavation to see what else can be learned about these prehistoric people.

The new discovery follows on the heels of a similar Scottish finding. In 2013, researchers in that country found a cache of flint tools on the Isle of Islay, evidence that Paleolithic people once lived in Scotland. Before that, researchers had evidence only of Mesolithic people in the United Kingdom's northernmost country.

The new findings were detailed online Monday (March 21) in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus