Food for Thought: Human Teeth Likely Shrank Due to Tool Use

Wisdom teeth may have shrunk during human evolution as part of changes that started with human tool use, according to a new study.

The research behind this finding could lead to a new way of figuring out how closely related fossil species are to modern humans, scientists added.

Although modern humans are the only surviving members of the human family tree, other species once lived on Earth. However, deducing the relationships between modern humans and these extinct hominins — humans and related species dating back to the split from the chimpanzee lineage — is difficult because fossils of ancient hominins are rare. [Image Gallery: Our Closest Human Ancestor]

Teeth are the hominin fossils most often found because they are the hardest parts of the human body. "Teeth are central to how a fossil ancestor lived, and can tell us about which species they belonged to, how they are related to other species, what they ate, and how quickly or slowly they developed during childhood," said lead study author Alistair Evans, an evolutionary biologist at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia.

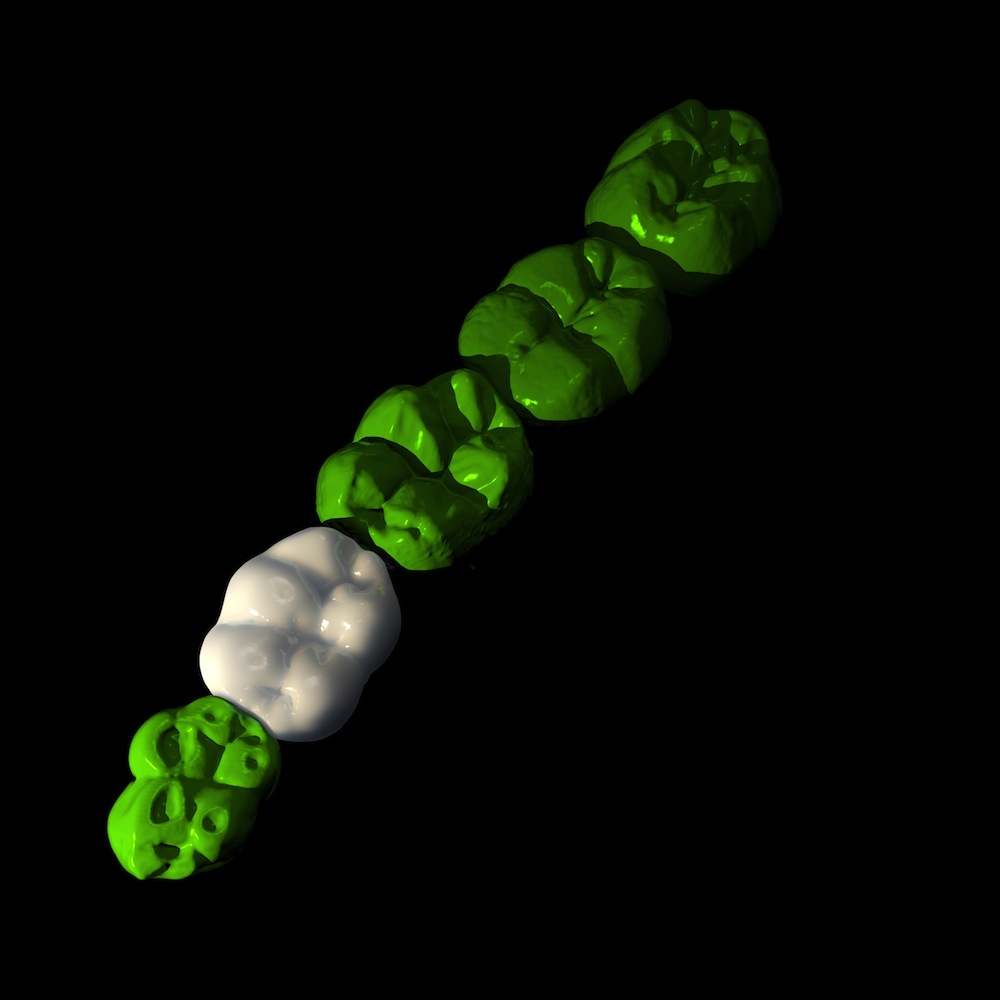

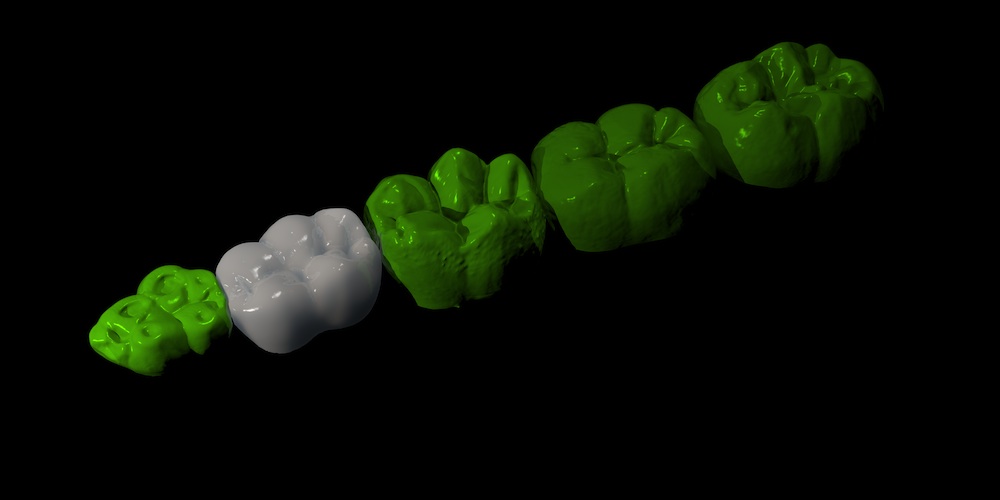

Hominin teeth have shrunk in size throughout evolution, a trend perhaps most clearly seen with the wisdom teeth located at the back of the mouth, the researchers said. In modern humans, wisdom teeth are often very small or do not even develop, while in many other hominin species they were huge, with chewing surfaces two to four times larger than those of their modern human counterparts.

Previous research suggested this profound shrinking in modern human wisdom tooth size was due to the advent of cooking or other changes in diet unique to modern humans. However, Evans and his colleagues now suggest this shift may have begun much earlier in human evolution.

The scientists analyzed tooth size in modern humans and fossil hominins. They found that hominin teeth fell into two major groups. One group was composed of the genus Homo, which includes both modern humans and extinct human relatives. The other group was made up of early hominins preceding Homo, such as the australopiths, the first primates to walk on two feet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In australopiths and other early hominins, the scientists found that teeth tended to get bigger toward the back of the mouth, with proportions that stayed constant regardless of the overall size of the teeth. However, in the genus Homo, the smaller all the teeth were, the smaller the teeth were toward the back of the mouth.

"There seems to be a key difference between the two groups of hominins — perhaps one of the things that defines our genus Homo," Evans said in a statement.

This change in how teeth developed between genus Homo and earlier hominins may have occurred due to the advent of advanced tool use in the genus Homo, Evans said.

"It's always been presumed that sometime in early Homo, we started using more advanced tools," Evans told Live Science. "Tool use meant we didn't need as big teeth and jaws as earlier hominins. This may then have increased evolutionary pressure to spend less energy developing teeth, making our teeth smaller."

In modern humans, tooth-size reduction has reached the point where wisdom teeth are increasingly failing to develop, Evans said. "The advent of cooking made food easier to eat, meaning we didn't need big teeth as much," Evans said.

Prior work suggested there was a lot of variation in how teeth evolved in hominins. "Now we're seeing some very simple, clear patterns in hominin tooth evolution instead," Evans said. [Infographic: Human Origins – How Hominids Evolved]

These patterns could help researchers decide whether ancient hominins were members of genus Homo or not, Evans said.

"It's been suggested a number of times over the past 20 years that maybe Homo habilis, often considered the earliest member of Homo, should be considered an australopith instead," Evans said. "We found Homo habilis tooth proportions followed the australopith rule and not the Homo rule, which supports the argument that Homo habilis should be reclassified to something like Australopithecus habilis."

This new work builds on previous experiments with mice that suggested teeth could influence each other during development. In this "inhibitory cascade model," teeth that develop early can inhibit the size of teeth that develop later. These new findings suggest this mechanism underlying tooth size in mice and most mammals is seen in hominins as well, Evans said.

These findings suggest that by knowing the size of a single hominin tooth and the group to which it belongs, scientists could infer the size of the hominin's remaining teeth with considerable accuracy. "Sometimes we find only a few teeth in a fossil," Evans said. "With our new insight, we can reliably estimate how big the missing teeth were."

Future research could analyze controversial hominin discoveries such as Homo naledi, recently unearthed in South Africa, Evans said. "It's got an interesting mix of traits, some that look like Homo, some that look australopith," Evans said. "It'd be interesting to examine its teeth and see which pattern it fits best."

The scientists detailed their findings in the Feb. 25 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.