New tests now officially confirm what doctors have long suspected: The Zika virus can cross the placental barrier in a pregnant woman and enter the amniotic fluid, the protective fluid that surrounds a developing fetus within the womb.

However, the findings do not show that the Zika virus causes microcephaly, a congenital condition in infants that causes them to be born with very small heads, the researchers cautioned.

"Previous studies have identified Zika virus in the saliva, breast milk and urine of mothers and their newborn babies" after the mothers had given birth, lead study author Dr. Ana Maria de Filippis, of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro, said in a statement. "This study reports details of the Zika virus being identified directly in the amniotic fluid of a woman during her pregnancy, suggesting that the virus could cross the placental barrier and potentially infect the fetus," she said. [5 Things to Know About Zika Virus]

Rise in microcephaly

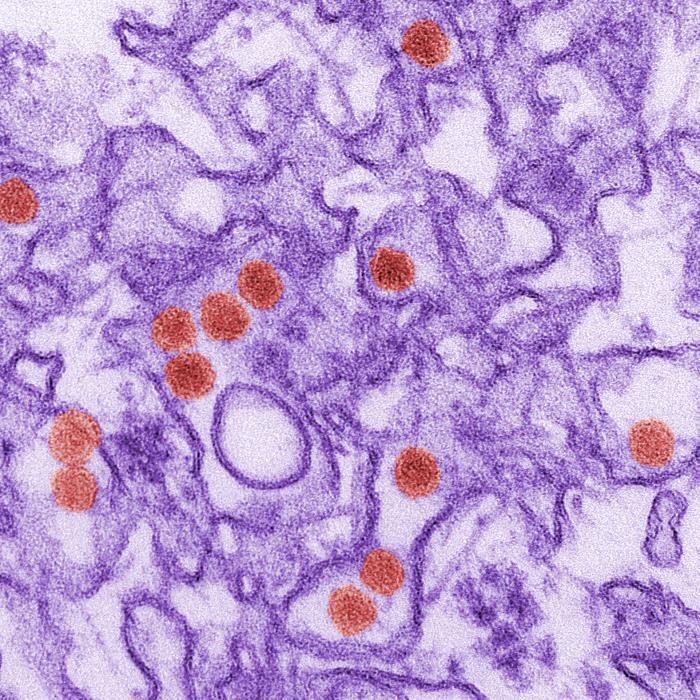

The Zika virus spreads via the bite of infected mosquitoes. It was first discovered in 1947 in Uganda and, for years, was thought to cause only mild symptoms, such as a low fever, rash, red eyes and body aches. However, after a large Zika outbreak began spreading in Brazil, doctors noticed a dramatic increase in the number of babies born with microcephaly.

Doctors have reported 20 times more cases of microcephaly in 2015 compared to 2014.

For the new study, which is published today (Feb. 17) in the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases, de Filippis and her colleagues examined samples of amniotic fluid from two women from Paraiba, Brazil, who had symptoms of Zika infection in the first trimester of their pregnancy. In their 22nd week of pregnancy, ultrasounds showed that the babies had microcephaly.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Although the women's blood and urine tested negative for Zika virus, their amniotic fluid tested positive for Zika virus.

Moreover, the virus that was present had a genetic sequence similar to that of a strain that first circulated in French Polynesia in 2013.

Although the researchers had previously reported to health officials their findings that the virus could enter amniotic fluid, the report is the first publication of peer-reviewed results that also analyze the genetic sequence of those strains.

Determining the risk

Microcephaly can be caused by many factors, including genetic disorders and drug use. But there is strong circumstantial evidence tying Zika to the condition. A September 2015 study in the journal BioMed Central found that viruses from the same family as Zika can cause microcephaly in infected animals. And other viruses that cross the placenta— such as HIV, herpes and chikungunya — can also cause microcephaly in human infants.

What's still unknown is whether Zika should be added to the list.

"This study cannot determine whether the Zika virus identified in these two cases was the cause of microcephaly in the babies," de Filippis said. "Until we understand the biological mechanism linking Zika virus to microcephaly, we cannot be certain that one causes the other, and further research is urgently needed."

To sort that out, doctors are currently conducting case-control studies to study and compare babies born with microcephaly to healthy babies from the same region born around the same time.

"Even if all these data strongly suggest that Zika virus can cause microcephaly, the number of microcephaly cases related to Zika virus is still unknown," Didier Musso, an infectious-disease researcher at the Louis Malarde Institute in Tahiti who was not involved in the study, said in an editorial accompanying the new findings.

"The next step will be to do case-control studies to estimate the potential risk of microcephaly after Zika virus infection during pregnancy, other fetal or neonatal complications, and long-term outcomes for infected symptomatic and asymptomatic neonates [newborns]," Musso wrote.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.