Meet 'Squishy Fingers': Flexible Robot Advances Undersea Research

There's a new soft and squishy robot in town, and it's ready for some serious underwater business.

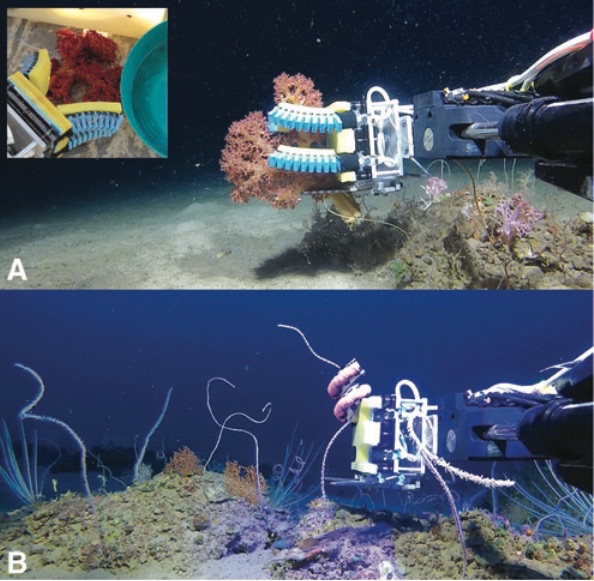

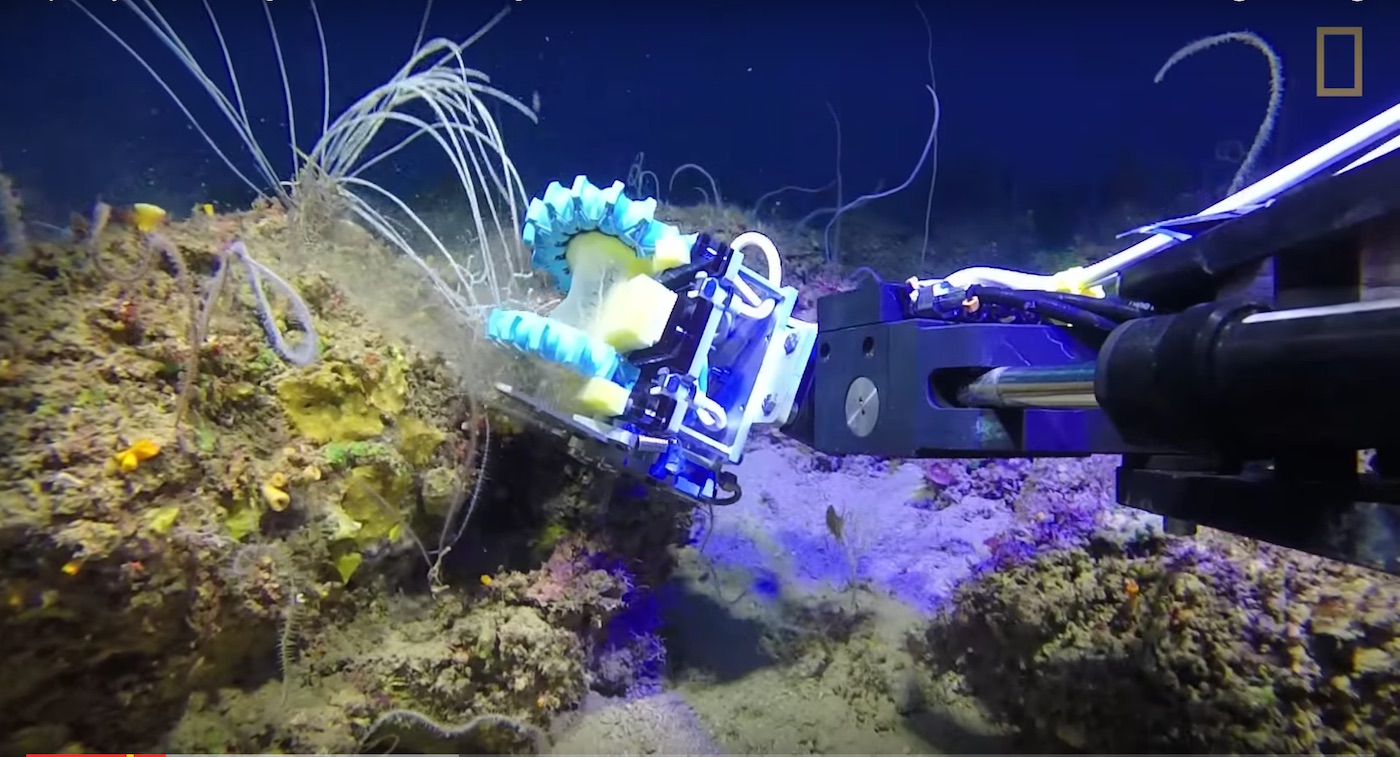

Meet "Squishy Fingers," a new remotely operated vehicle designed to delicately grab and take samples of coral. The ROV, described in a Jan. 20 study in the journal Soft Robotics, will help researchers collect specimens from deep underwater reefs without damaging the corals' fragile bodies.

"If we're going to go down and study these systems, then we should be as gentle as we possibly can," said study co-senior author David Gruber, an associate professor of biology at Baruch College in New York City and a National Geographic emerging explorer. [Marine Marvels: Spectacular Photos of Sea Creatures]

Until now, coral researchers used clunky and rigid ROVs originally developed for the oil and gas industries. These vehicles' stiff arms were made to do heavy work, such as turning pipes off and on, rather than plucking tiny organisms off a coral reef.

"These arms can generate lifting and gripping forces up to 500 lbs.-force [227 kilograms-force] and are not optimal for delicate specimen collection," the researchers wrote in the study.

Enter soft robotics expert Robert Wood, study co-senior author and a professor of engineering and applied sciences at Harvard University.

"Rob was looking at the [ROV], and he was like, 'Oh my God, that's how you guys are collecting stuff? That doesn't look very effective,'" Gruber recalled.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

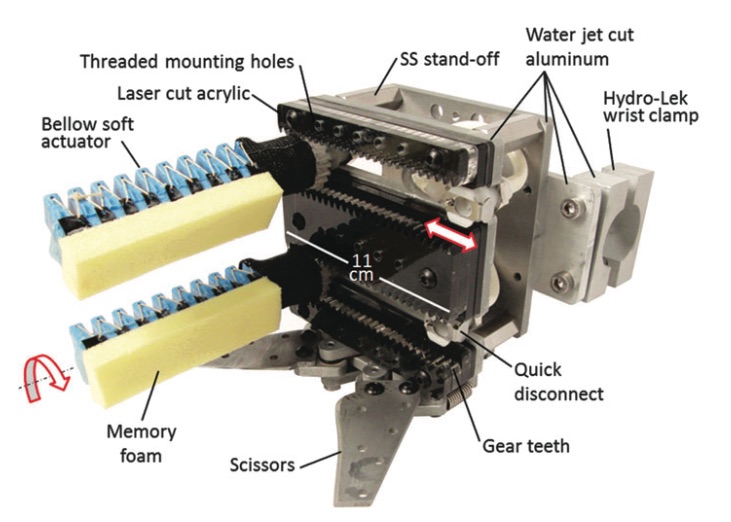

So the two assembled a team and got to work designing "Squishy Fingers," an ROV with a soft but firm grasp. The team took inspiration from sea creatures, such as the tube worm and the snake (which can wrap itself about things).

The final fingers are largely made of memory foam, silicone rubber, fiberglass and Kevlar fibers.

Humans can't safely scuba dive beyond 330 feet (100 meters) of water, so it's important that Squishy Fingers can dive deeper and retrieve hard-to-reach creatures, Wood told National Geographic. So far, the joystick-controlled squishy robot has successfully completed a dive at about 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) depth, but the researchers hope to design an upgrade that can reach 3.7 miles, or 3,168 feet (6 km), Gruber said.

Eventually, the team hopes to create a "Squishy Arms" robot that has a greater capacity to collect deep-sea organisms, he added.

The specimens collected by these squishy ROVs will help researchers study the genomes and proteins of mysterious underwater plants and animals, as well as identify new species, Gruber said.

"It's one thing to just see them, but you can't identify a new species just by looking at it or just by taking a new picture," Gruber told Live Science. "Sometimes you need to take one sample, or even get things like a vein biopsy sample in order to sequence its genome."

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.