Weird Mucus Parasites Are Actually Jellyfish

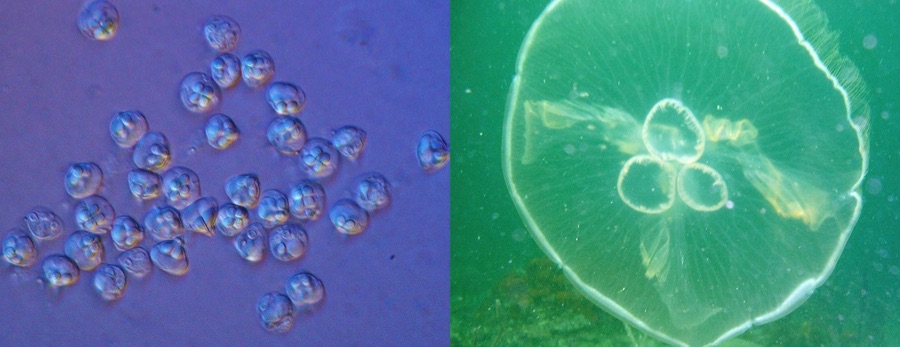

Microscopic parasites only a few cells large are essentially greatly degenerated jellyfish, a finding that could expand the definition of the animal kingdom, researchers say.

"When people think of an animal, they think of a macroscopic, multicellular, complex organism, and now they'll have to expand their definition of an animal to include very simple microscopic organisms," study co-author Paulyn Cartwright, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Kansas,told Live Science.

Investigators analyzed myxozoans, a very diverse group of more than 2,100 microscopic parasites whose name means "mucus animals" in Greek, which refers to how scientists thought they were once associated with slime molds. [See Amazing Photos of Jellyfish Swarms]

Myxozoans commonly plague commercial fish, infecting them as part of their life cycle. For instance, they can cause whirling disease in trout and salmon, where the parasites attack the brain and spinal cord and make fish start swimming in circles.

Although scientists have investigated myxozoans since the 1880s, much about the evolutionary origins of these parasites was uncertain.

"Some people originally thought they were single-celled organisms," Cartwright said in a statement. "But when their DNA was sequenced, researchers started to surmise they were animals — just really weird ones."

For instance, prior research found that myxozoans lack so-called Hox genes, which are generally vital to embryonic development in animals. "Because they're so weird, it's difficult to imagine they were jellyfish," Cartwright said in a statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Myxozoans are extremely simple organisms consisting of just a few cells and lacking a mouth or a gut. However, previous research found that myxozoans possess complex structures that resemble the stinging cells of cnidarians, the group that includes jellyfish, corals and sea anemones.

After the researchers analyzed genomes from two distantly related myxozoan species, they found the parasites are actually cnidarians. They were most closely related to medusozoans, the cnidarians that include jellyfish.

"This is a remarkable case of extreme degeneration of an animal body plan," Cartwright said in a statement.

The myxozoans not only had stripped-down bodies — the bell-shaped part of a traditional jellyfish — but also had drastically simplified genomes.

"These were 20 to 40 times smaller than average jellyfish genomes," Cartwright said in the statement. "It's one of the smallest animal genomes ever reported. It only has about 20 million base pairs, whereas the average cnidarian has over 300 million. These are tiny little genomes by comparison." (Humans, for comparison, are equipped with 3 billion pairs of bases in our genomes.)

This degeneration of the genome was unexpected. "A lot of small organisms have big genomes, and big organisms can have small genomes," Cartwright said. "I think the easiest explanation for what happened with myxozoans was that they experienced an extreme case of degeneration to just a few cells, and many genes were no longer needed."

The researchers now want to learn more about how this degeneration occurred.

"First, we confirmed they're cnidarians," Cartwright said in the statement. "Now we need to investigate how they got to be that way."

Future research might turn up other instances of such extreme degeneration.

"It would be hard to recognize such animals because they would look so different from their closest relatives," Cartwright said. "I think with new technologies such as whole-genome sequencing, we can better identify the evolutionary origins of some of these strange creatures."

The scientists detailed their findings online today (Nov. 16) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.