Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Werewolves, witches and zombies? Yawn.

Though these imaginary Halloween beasties may conjure fright in some people, they don't hold a candle to some of the real-life horrors that have terrorized people in the past. The annals of history are littered with madmen, monsters and weirdos whose sick and evil deeds continue to send chills down peoples' spines.

From the countess who bathed in blood to the real Dracula, here are some of the scariest real-life figures. [The Real Dracula: All About Vlad the Impaler]

1. Vlad the Impaler

Vlad III Dracula, a 15th-century prince of Wallachia (in what is now Romania), is even more frightening than the blood-sucking vampire stories he inspired. The prince grew up in Romania, but spent many years in the Ottoman Empire as a political hostage of then-ruler Sultan Murad II. Though Vlad III was treated fairly well, even learning the arts of war from his captors, he maintained a bitter hatred for the Ottomans. Some historians speculate that the bloodthirsty Vlad developed his knack for especially horrifying torture — including his signature trick of impaling his enemies on spikes — during his years as an Ottoman captive.

Vlad eventually returned to Wallachia, and in short order, his old nemesis, Sultan Murad II, invaded. Walking into the capital city, the sultan encountered a grisly site: rotting Ottoman prisoners of war were impaled on spikes, a kind of psychological warfare Vlad used to unnerve his enemies given his limited military means.

Whether Vlad deserves his vampiric reputation is less clear. A 15th-century German poem, which is now held at the Heidelberg University in Germany, may depict the man feasting on blood, dipping his bread into the blood of impaled victims or washing his hands in blood before eating. However, historians dispute the interpretation of the poem.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Vlad's reputation as a vampire likely stems from the 19th-century novel "Dracula" by author Bram Stoker, who visited Vlad's castle in Transylvania and combined the brutal Wallachian ruler's history with local folktales about "moroi," the spirits of dead children who drank the blood of cattle. [7 Strange Ways Humans Act Like Vampires]

2. Countess Bathory

Though Vlad III certainly had his share of gory feats, he's no match for Countess Bathory, a noblewoman who lived in the 16th century. Bathory, often nicknamed Countess Dracula, has earned the dubious moniker of "most prolific female serial killer," and may have slaughtered hundreds of young women.

"A straightforward dramatization of the crimes alleged against her in her lifetime — the murder of more than 600 women, genital mutilation, cannibalism — would entail a bloodbath — literally and figuratively — that would stretch the tolerance of most liberal end-of-century censors and risk unsettling even the most hardened aficionado of splatter movies," wrote Tony Thorne in "Countess Dracula: The Life and Times of Elizabeth Bathory, The Blood Countess" (Bloomsbury Press, 1997).

Bathory would lure young peasant girls (and later lower-level gentlemen's daughters) to the castle, either to act as maidservants or to learn decorum. She or a few trusted underlings then beat, mutilated and even bit off the faces of the young women, often leaving them to starve to death. Legends depict Bathory literally bathing in the blood of her victims, believing it would help her maintain a youthful appearance. Her reign of terror ended only when her guardian caught her in the act of murder and torture.

At Bathory's trial in 1611, dozens of witnesses and victims described her atrocities in minute detail. However, some historians question the veracity of allegations against the countess, arguing that political enemies may have exaggerated the charges against her to slander her name and claim her lands as their own.

Despite her alleged brutality, Countess Bathory had a more peaceful death than many of her victims: After being imprisoned in her own castle tower for years, in 1614, she complained of cold hands and was dead by the next morning.

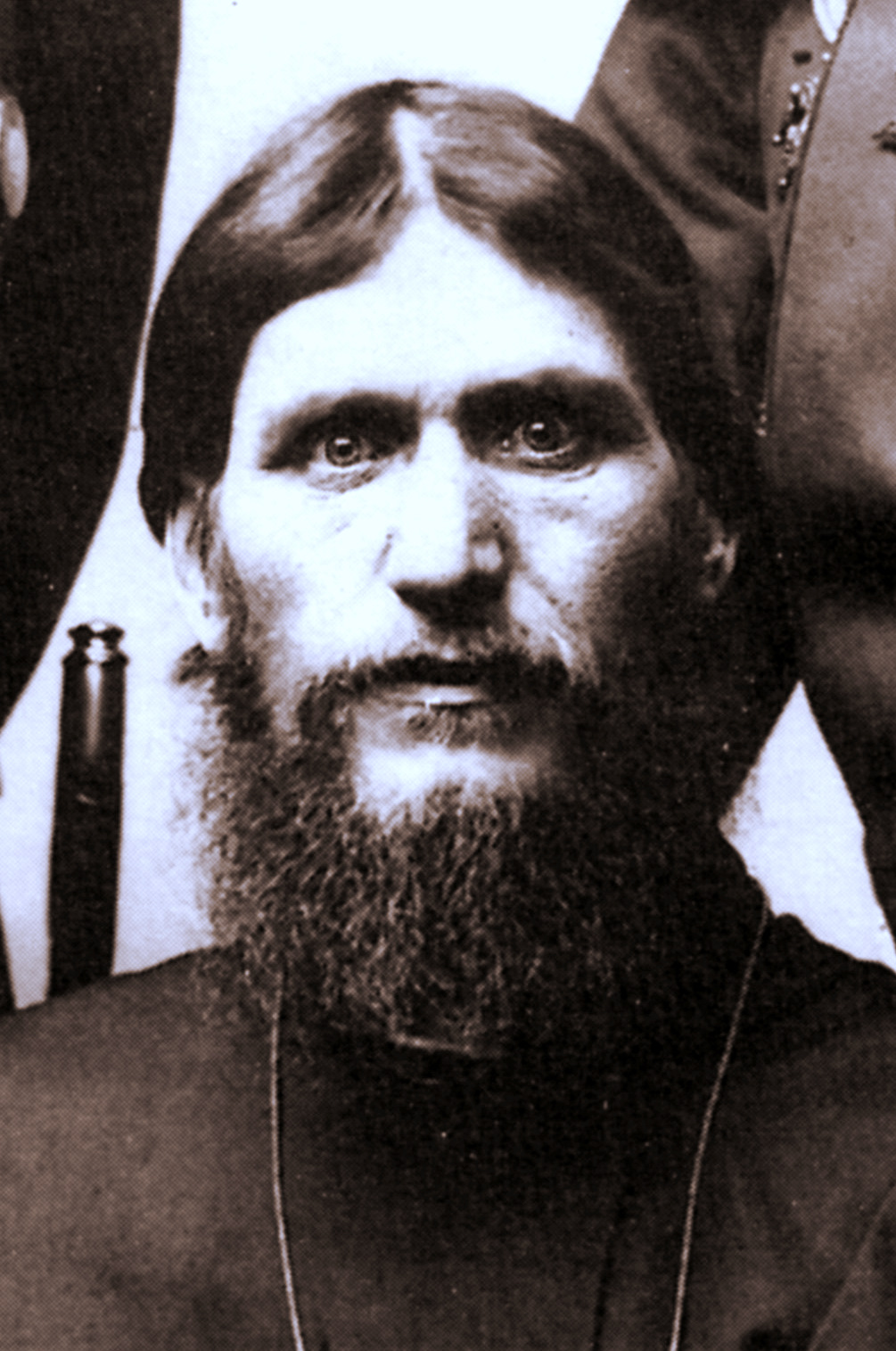

3. Rasputin

Grigori Rasputin, a Russian mystic born in 1869 who came to influence the last czar of Russia, inspired fear and loathing in the people. The straggly bearded, dead-eyed itinerant preacher gained close access to the Russian ruler's family after Czar Nicholas' son Alexei suffered an injury that became life threatening due to a blood-clotting disorder.

The family believed Rasputin's holy ministrations saved Alexei, and the "mad monk" soon entered the family's inner cadre. But many Russian nobles hated the creepy mystic's hold on the royal family, and worried that his shady influence was leading the country astray.

Rasputin's unique definition of holiness drew widespread disgust. He believed it was necessary to wallow in sin in order to achieve redemption. By that logic, Rasputin drank like a fish, cheated on his wife openly and cavorted with scoundrels (and presumably then felt really bad about it). Over time, rumors of rape, Satanism and occult practices swirled around him, wrote Joseph Fuhrmann in "Rasputin, the Untold Story," (Wiley, 2012).

Still, the creepiest thing about Rasputin may have been his death. When Russian aristocrats decided they'd had enough of Rasputin's influence on the czar, they conspired to poison the mystic, and when that failed, they shot him several times. According to lore, Rasputin survived those shots and arose like a zombie. The conspirators then beat him to unconsciousness, and he was still alive when they threw him to his death in the Neva River, as described in "Rasputin, the Untold Story."

4. Attila the Hun

When someone's preferred nickname is "the Scourge of God," you know he's not winning any awards for kindness. Attila, the king of the Huns, terrorized Europe, and his constant raids in the fifth century helped hasten the Roman Empire's downfall.

Even at that chaotic time, when brutality and torture were commonplace, Attila stood out as particularly bloodthirsty. He killed his own brother, Bleda, to gain control of the Huns, as described in "History of the Later Roman Empire," (Courier Corporation, 1958). Attila raped and pillaged his way through Europe, and his main military tool was terror.

When the Huns went on the rampage, they would arrive on horseback with blood-curdling screams. For extra effect, Attila was known to tie the skulls of vanquished enemies to his saddle, as described in "The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire," (Harper and Brothers, 1836).

In Attila's bloody tenure, he sacked over 70 cities, leaving behind little more than rubble and ashes. He is said to have been responsible for the deaths of 1 million people, no mean feat at a time when warriors relied on old-school weapons such as swords, stated the "History of the Later Roman Empire."

Attila met his death at his own red wedding. According to the sixth-century historian Jordanes, Attila was recovering from revelry after one of his marriage feasts (the man had many wives) when he burst an artery and choked on blood gushing into his nose and throat.

Still, accounts by the fifth-century Roman diplomat Priscus show Attila had a good side. The ultimate brutal warrior could show loyalty, generosity and even mercy when it suited him. And though he may have made ancient Roman citizens tremble, plenty of other rulers, such as Genghis Khan, gave him a run for his money when it came to barbarity. [8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

5. Gilles de Rais

When Joan of Arc led her successful campaign against the English in the Hundred Years' War, she had one particularly fearless knight, named Gilles de Rais, at her side. But de Rais's greatest claim to fame wasn't his bravery — it was his part-time hobby of murdering children. The knight ordered his underlings to bring him children for torture and murder. All told, he is believed to have slaughtered anywhere from 80 to 800 children. After sexually assaulting the children, de Rais would have their heads and then other body parts cut off one by one using a sword called a braquemard, which was reserved especially for the gory task, wrote Reginald Hyatte in "Laughter for the Devil: The Trials of Gilles De Rais, Companion-in-Arms of Joan of Arc (1440)" (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1984).

As early as 1432, rumors of de Rais' murderous rampage were circulating. A quarrel with a church member incited the Catholic Church hold a trial to examine the rumors. At the trial, the true extent of the knight's horror came to light, with the parents of lost children and de Rais' own conspirators testifying to his atrocities. He was hanged in 1440.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus