Unusual Parasite from Organ Donor Sickens 3 People

Three people who received organ transplants from the same donor all developed serious brain problems shortly after their operations. The mysterious symptoms turned out to be due to a little-understood parasite that infected the donor before she died, according to a new report of the case.

The donor was a 43-year-old woman who died from a stroke, and her kidneys, heart and liver were all transplanted into patients in February 2014. But two months later, a man who received a kidney from the woman developed a fever, and showed changes in behavior, suggesting a brain problem.

Doctors were concerned that the man had contracted an infection from the donor, which happens in about 1 to 2 percent of U.S. transplants. The physicians tracked down the two other transplant patients — one who received the liver, and another who received both the donor's heart and other kidney. The patient who received the liver transplant had already seen a doctor because of tremors and problems walking, and the heart and kidney transplant patient had been admitted to the hospital for brain inflammation known as encephalitis.

"All three [transplant] recipients developed severe neurological complaints within a few months of the transplant," said study researcher Dr. Rachel Smith, a medical epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [The 9 Most Interesting Transplants]

Doctors tested the patients' blood, urine, stool and cerebrospinal fluid for a number of infections, but all the tests were negative.

The patient with the kidney transplant got progressively worse over the next few months, and died in May.

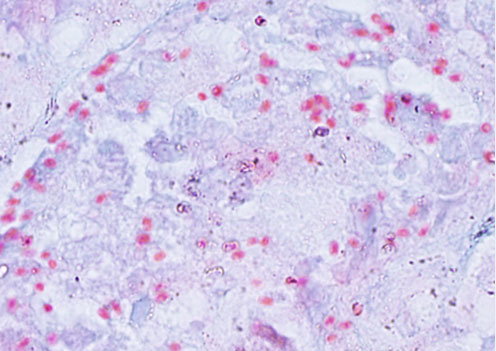

During that patient's autopsy, doctors tested the man's tissue for infections, and the test was positive for a parasite called Encephalitozoon cuniculi, which belongs to a group of single-celled organisms known as microsporidia. Subsequent tests showed that both the donor and the two surviving transplant recipients also were infected with the parasite.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most patients with this parasite have gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, and it's rare for them to have only brain symptoms, Smith said. Usually, microsporidia infection leads to disease only in people with compromised immune systems. That group includes transplant patients, who must take medications that suppress the immune system to prevent their bodies' from rejecting the new organ.

But this parasite "may be more common than we think," Smith said. It's difficult to diagnose, and whether it ever causes symptoms in healthy people, or goes away on its own, is not known. It may be that the organ donor carried the parasite in her body for a long time without ever having symptoms, Smith said.

Still, the parasite is rare in transplant patients, and it's unlikely that doctors would begin routinely testing organ donors for microsporidia at this time, Smith said. The parasite is a challenge to diagnose, and doctors are not certain what a positive result means in terms of patient safety, she said.

"There's always this tension between making sure that transplants are safe and making sure that no more people die on the waiting list than is already happening," Smith said. "Anytime we say that there should be another test done on donors, it needs to have a very obvious value added to the safety component of this."

Both of the surviving transplant recipients were given a drug called albendazole, and their neurological problems went away. More research is needed to better understand how to treat and diagnose these infections, Smith said.

Smith presented the findings this month at IDWeek, a meeting of several organizations focused on infectious diseases.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus