Best US States for Child Kidney Transplants Revealed

Need a kidney for a sick child? Consider moving to Georgia, or one of the other states where the odds of quickly getting a life-saving kidney donation are much higher than in other places.

Waiting times for kidneys for children with renal disease can vary widely, from a few weeks to a few years, depending on which state you live in, according to a new analysis published today (Jan. 16) in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

This discrepancy is particularly troublesome, researchers say, because children awaiting a kidney transplant must undergo kidney dialysis treatment, the mechanical filtering of their blood, several times a week. The procedure is especially hard on their arteries, and studies have shown these children's risk of early death, often from cardiovascular disease, is four times higher compared with that for children fortunate enough to get a donated kidney.

Moreover, suitable kidneys are likely available to help the approximately 2,000 children nationwide waiting for a kidney transplant, if only the distribution could be handled better, said Dr. Sandra Amaral, of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania and senior author of the report.

Who gets a kidney?

Kidneys are distributed to transplant recipients based on their location, with the first priority going to those closest to the donor. Children do receive priority for kidneys from local deceased donors who are age 35 or younger, but a "young" kidney sometimes goes to a local adult, rather than to a child in a different state. [9 Most Interesting Transplants]

In the new study, the researchers looked at information from more than 3,700 pediatric kidney transplants from 2005 to 2010.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They found that the length of waiting times for high-quality kidneys was closely associated with local supply and demand: States such as Maryland and Texas, which had a low ratio of high-quality kidney donors to recipients, had the longest waits for children — more than 270 days, on average. In contrast, other states, including Maine and most of the Deep South, had a high donor-to-recipient ratio and the shortest waits, sometimes just a few weeks.

"Our study findings suggest that the current allocation system is failing children who have the misfortune of living in areas with the greatest organ shortage," Amaral said.

It doesn't have to be this way, Amaral told LiveScience, because this is an age of instant communication and rapid transportation.

"In the modern age, transporting organs across the country is still a concern, but a fairly minor one, thanks to better preservation methods to keep the organ healthy and better availability of high-speed travel," she said.

The researchers could not determine precisely why donor-to-recipient ratios vary so widely. Mississippi, for example, has one of the lowest registered-organ-donor rates in the country, according to data from Donate Life America, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to increase the number of designated organ, eye and tissue donors. Yet the state has a favorable donor-to-recipient ratio, with fewer children needing kidney transplants than in other states, the reason for which is unknown.

What could be done?

Amaral and the lead author of the report, Dr. Peter Reese, also of the University of Pennsylvania, recommend redefining the so-called local donation boundaries so that more children can have first consideration for high-quality kidneys that might otherwise go to adult patients. They also suggest restructuring how organs for children are distributed, and offering kidneys to the patients who need them most, on a regional or national basis, instead of first locally.

"It is important to keep in mind that children comprise a very small portion of the deceased-donor kidney-transplant waiting list, so policies that preferentially allocate organs to children won't have much impact overall on the adult population, but could really change the life of an individual child," Amaral said.

There are more than 100,000 kidney-transplant candidates, and only about 1,800 are pediatric patients, according to data from the federally run Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Amaral said the good news is that current allocation policies have greatly helped children in need get kidneys faster; the median wait time is 284 days for children, compared with about four years for adults. But the benefit isn't spread evenly across the country.

Reese added that children need "very-high-quality kidneys that will function well and last long while they grow up." A kidney from a deceased donor typically performs well for 10 or 15 years, which is not as much of a concern for a recipient who is 65 years old. "The main problem here is a shortage of really good kidneys for [the children]," he said.

Of course, more kidneys would help. An average of 18 people on the national organ waiting list die daily, according to the U.S. Division of Transplantation, the primary federal entity responsible for oversight of the organ and blood stem-cell transplant systems in the United States and for initiatives to increase the level of organ donation in the country.

Organ-donor registration varies state by state; Montana and Alaska lead, with more than 80 percent of the adult population registered as organ donors. Vermont has the lowest rate, at 5 percent, followed by Texas, with only 17 percent registered, according to the most recent Donate Life America "report card." Nationally, only about 45 percent of adults are registered organ donors.

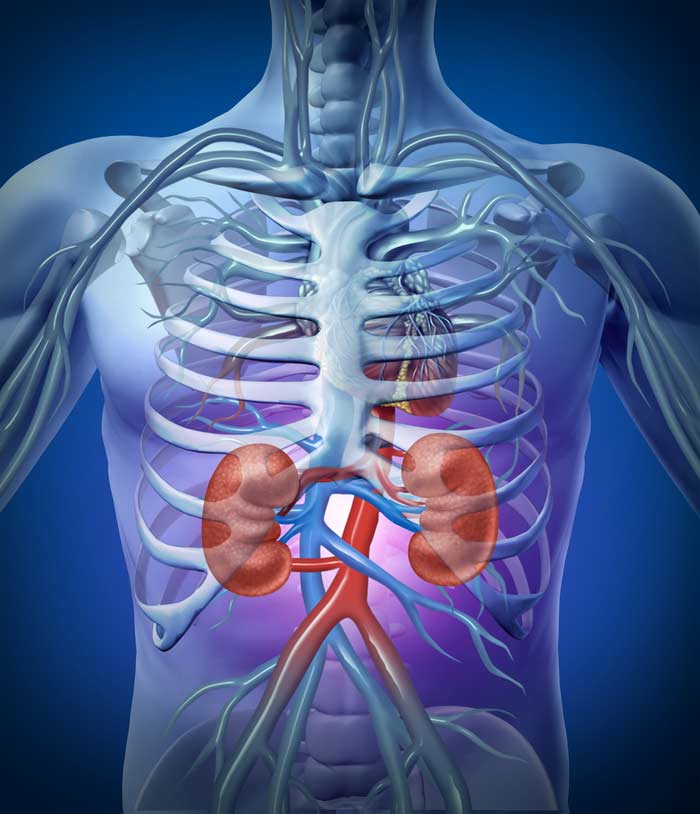

Humans are born with two kidneys but need only one, so live kidney donations remain an option, too.

Follow Christopher Wanjek @wanjek for daily tweets on health and science with a humorous edge. Wanjek is the author of "Food at Work" and "Bad Medicine." His column, Bad Medicine, appears regularly on LiveScience.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus