With Kinect, Kids May Clinch Clinical Trials (Essay)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

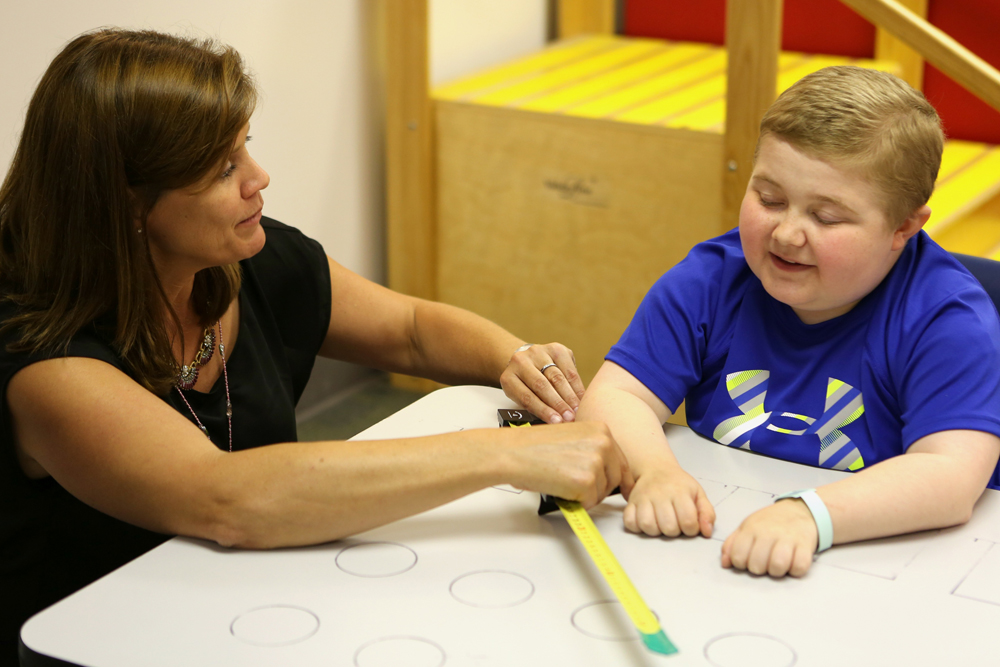

Lindsay Alfano, is a research therapist in the clinical therapies outpatient research department and the Center for Gene Therapy at Nationwide Children's Hospital. She contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Imagine having a child with a life-threatening disease, and then learning your child can't join research studies that might help find a cure. For thousands of parents whose sons who are living with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, it's a tragic reality.

In the United States, one out of every 3,600 boys is diagnosed with the disease, a genetic disorder that primarily affects males. The earliest symptom, muscle weakness, is not often noticeable at birth. But over time, parents notice their child is no longer keeping up with his peers. These children become weaker, eventually losing the ability to walk, feed themselves, or do everyday activities independently. Children with Duchenne transition to full-time wheelchair use around the ages of 10 to 12 years, and later in life begin to lose respiratory and cardiovascular function.

Currently, patients with diseases like muscular dystrophy who have lost mobility are often excluded from clinical trials — there is not an easy, affordable or comprehensive way to measure their muscular function. Clinical trials generally rely on timed walking tests, and walking is impossible for many of the boys affected by this disease.

In an effort to allow more children, despite the use of a wheelchair, to take part in clinical studies, our team at Nationwide Children's Hospital developed a way to measure children's upper body function — reach, arm and trunk strength — using interactive video game technology. Using this approach, we accurately and consistently track the patients' upper-body abilities over time, a key measurement for medical trials. Our goal is to demonstrate to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that our game provides accurate results, that patients perform repeated trials of the game consistently, and that the results will change according to the progress of the patient. If approved, then those patients will be eligible for future clinical trials. [Viagra Is a Miracle Drug, For Premature Babies (Op-Ed)]

So far, the results have been impressive. Our system, Ability Captured Through Interactive Video Evaluation, or ACTIVE-seated, technology uses a Kinect gaming camera from an Xbox console.

In our game, the boys reach with their arms in various directions to push away a force field — while simultaneously crushing spiders, digging through dirt or finding hidden objects. Using the Kinect camera, ACTIVE-seated software algorithms measure how far the boys reach in all directions.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The reachable area, which is visually represented as a series of boxes on a screen, is converted into a scaled score based on arm length. This standardizes comparisons between patients of different sizes and allows a patient to continue to participate even as he grows.

We recruited 61 patients from our hospital's Muscular Dystrophy Association Clinic for the study. We built the game almost entirely from patient input, because motivation is a key factor to the game's clinical success. This is critical for children. If a patient isn't motivated to do something day after day, performance levels will change, making the assessment tool useless.

Our hope is that our new approach will become standard, both in the United States and across the globe, as most muscular dystrophy clinical trials are currently conducted overseas. We think there's also a possibility that this method can be proven effective for patients with other conditions that result in lack of mobility, such as cerebral palsy.

In a typical clinical trial, when kids come in for appointments, they have to spend hours doing difficult tasks. But playing a video game is more fun, and we can see it on these boys' faces. For a moment, they can just focus on playing and being kids again.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus