Sex in the Wild: 6 Ways Animals Do It

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Valentine's Day may inspire people to buy chocolates for their loved ones or treat their sweetheart to a romantic, candlelit dinner, but animals have entirely different courtship behaviors. Often the male makes a grand gesture. Male koalas bellow at females, and male penguins may build the female a nest or sing for her. The male octopus, on the other hand, often has to flee to avoid the female's penchant for cannibalism. Here are some ways animals get in the mood.

How koalas do it

Male koalas bellow their mating calls in the midnight hour. From 12 a.m. to 4 a.m. during mating season in the spring and summer, these furry marsupials bellow at potential partners using a structure in their larynx. Like an online dating profile, each bellow is unique to the caller, and tells other koalas about the suitor's size, Bill Ellis, a koala researcher with the University of Queensland in Australia, told Live Science last year.

Female koalas choose a new mate every year, and the bellows likely help the females find a desirable male, Ellis said. If she's interested, the female koala will venture into the male's territory to get a better look. If she changes her mind, she'll cry and leave. The male may force himself on her, but the female koala will "do everything in her capacity to reject him," and will bite and scratch the male, Ellis said.

To mate, the male climbs on the female's back, bites her on the back of her neck and gets down to business. (Photo credit: covenant | Shutterstock.com) [Read more about koala sex]

How porcupines do it

How do porcupines mate in spite of their pointy quills? Very carefully, the saying goes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Porcupines can be divided into two broad groups: Old World and New World. Old World porcupines live on the ground in family groups, whereas New World porcupines live in trees and are usually solitary animals. The two groups have different mating strategies.

Old World porcupines are monogamous and breed together throughout the year, porcupine expert Uldis Roze, a professor emeritus of biology at Queens College in New York City, told Live Science last year.

Little is known about New World porcupine copulation, but the female North American porcupine is fertile for just eight to 12 hours a year, Roze said. Mating season happens in September, when the female secretes strong-smelling vaginal mucus and uses her urine to attract males. The males may fight each other for the chance to mate, and can leave scars and torn ears in their wake.

The winning male climbs onto the low branch of a tree, and sprays the female with a blast of urine to stimulate her into estrous. She'll shake it off if she's not interested, Roze said. But if she is, the female porcupine will curve her tail over her back so that the male won't be impaled when he mounts her. (Photo credit: A_Lein | Shutterstock.com) [Read more about porcupine sex]

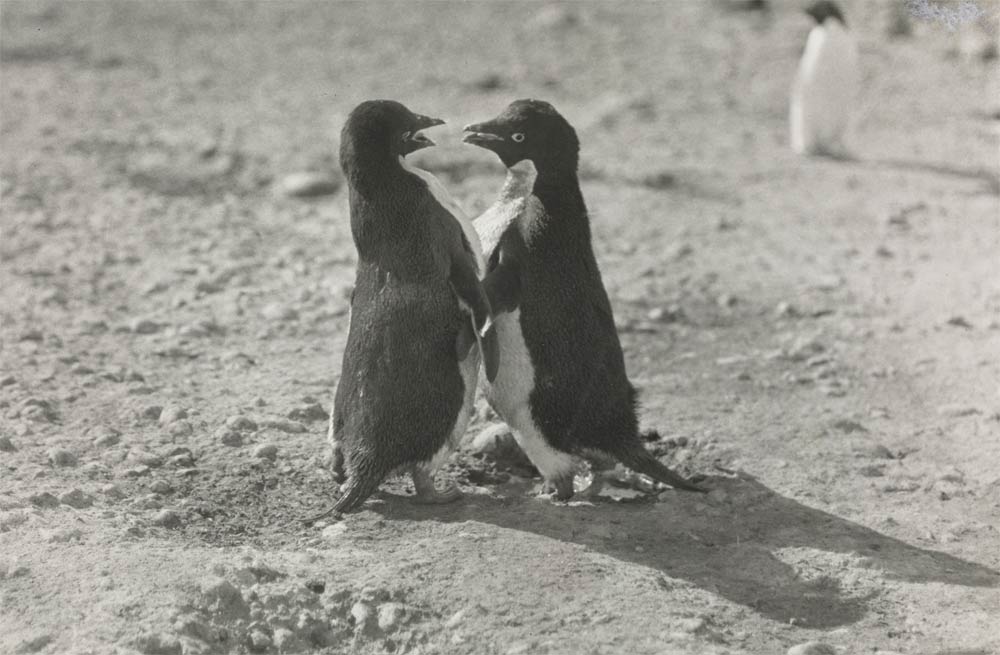

How penguins do it

The season of love for most penguins happens during the Antarctic summer, from October to February. To woo females, males either find a place in the colony or build or remodel a nest from the previous year.

Though it may take a few weeks, female penguins follow and join their mates from the last year. The females inspect the nests, and may also check out neighboring nests. But the neighbors don't always appreciate the company.

"If the male's previous partner arrives, she will kick the new female out of the nest," penguin researcher Emma Marks, of the University of Auckland in New Zealand, told Live Science in a previous interview. "It's a little bit like watching a soap opera."

Male penguins that don't build nests may sing to females. These notes may help females gauge how fat a male is, which would make him a good babysitter for the eggs, experts said.

After a female picks her mate, the two birds bow, preen and call to one another. The female then lies down on the ground, and the male climbs on her back to do the dirty deed. (Photo credit: copyright Natural History Museum) [Read more about penguin sex]

How octopuses do it

The male octopus uses a detachable penis to impregnate the female, but first he has to find her.

Male octopuses search far and wide for females, and may rely on chemical cues to locate a mate, experts say. But once he finds a female, the male octopus has to be careful, because females often try to kill and eat the males after copulation.

The male inserts a detachable penis, called a hectocotylus, into the mantle cavity of the female, where he deposits sperm packets called spermatophores. If the male survives, he will regenerate a new hectocotylus.

Different species of octopus have other mating systems. Pairs of the Pacific striped octopus mate mouth to mouth and sucker to sucker. (Photo credit: Mana Photo | Shutterstock.com) [Read more about octopus sex]

How anglerfish do it

Few people see the sharp-toothed anglerfish get it on, because this animal lives in the deep sea, at depths below 948 feet (300 meters). Males are much smaller than females, and spend their entire lives searching for a mate. Depending on the species, the males may use their sensitive noses or excellent vision to locate a lady.

Once he finds her, the male will latch onto the female, allowing their tissues to fuse and their circulatory systems to connect.

Once fused, "the male becomes permanently dependent on the female for blood-transported nutrients, while the host female becomes a kind of self-fertilizing hermaphrodite," anglerfish expert Ted Pietsch, curator of fishes at the Burke Museum at the University of Washington, told Live Science in January. (Photo credit: (c) 2014 MBARI) [Read more about anglerfish sex]

How Ulidiid flies do it

After the female Ulidiid fly mates, she expels the male's sperm and eats it.

Researchers found this odd behavior in all of the 74 fly couples they studied. It's possible that snacking on sperm helps the female flies decide which male will father her children, the researchers said.

One-quarter of the females did not contain any sperm after they ate it, which suggests they're able to control how much sperm to expel or keep, the study found.

Interestingly, the longer the fly courtship, the more likely the female was to expel all of the ejaculate, the researchers found. Perhaps the female had finally caved to a persistent male, but then got rid of his sperm after the deed.

The sperm may also provide the female with a nutritious snack, the researchers said. The jury is still out on whether she would prefer chocolate and flowers instead. (Photo credit: Elliotte Rusty Harold | Shutterstock) [Read more about Ulidiid fly sex]

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus