Hidden Faults Explain Earthquakes in Fracking Zones

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Oklahoma, Ohio and Arkansas have experienced an unusually large number of earthquakes in recent years.

The shaking is rising at the same time that oil and gas production have increased. But other states that are hotbeds for new drilling have stayed seismically quiet, such as Montana, North Dakota and South Dakota.

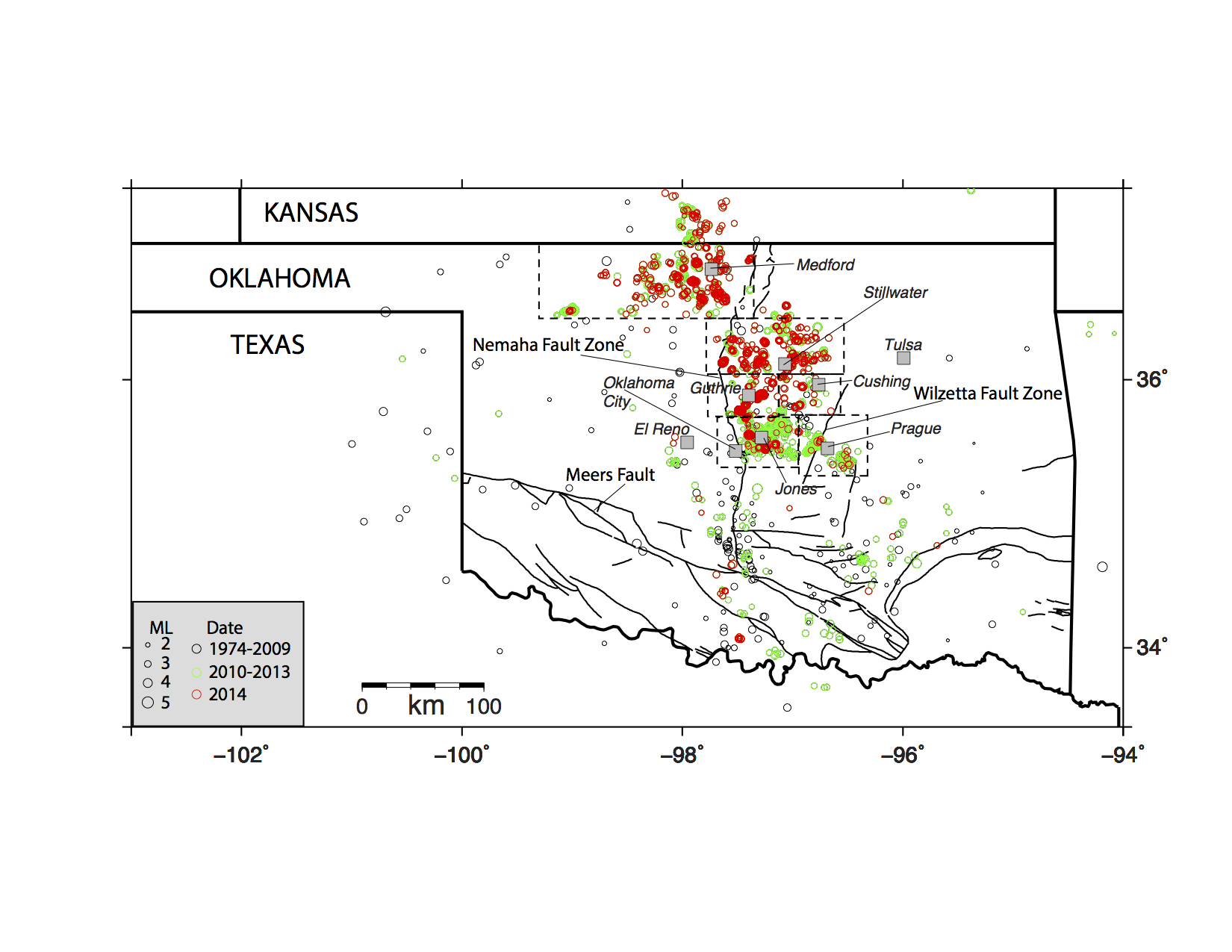

Now, two new studies explain why some regions of the country are rattling more than others. In Oklahoma, hidden faults beneath the surface are primed to pop, reports a study published Jan. 27 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. Some of these faults were previously unknown and threaten critical structures, such as huge oil-storage facilities, said lead study author Daniel McNamara, a U.S. Geological Survey research geophysicist based in Golden, Colorado. But the geology underlying Montana and the Dakotas is more benign, with fewer faults near their breaking point, according to a study published Feb. 10 in the journal Seismological Research Letters. [Top 10 Ways to Destroy Earth]

In the first study, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) analyzed more than 3,600 recent Oklahoma earthquakes to precisely locate known and unknown faults.

The majority of the faults are perfectly aligned to slip under pressure transmitted through the continent from faraway tectonic plate boundaries, the study reports. Oklahoma's buried rock layers are squeezed in an east-west direction from forces at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, San Andreas Fault and Juan de Fuca Ridge, McNamara said. But the underground faults identified in the study tilt to the northwest or northeast, creating an angle of about 30 to 40 degrees from this regional pressure.

"This is the optimal orientation for producing strike-slip faulting," McNamara told Live Science. If the faults were more steeply tilted in either direction, it would be harder to force them to jerk apart. (Imagine mashing together two bricks that point toward noon on a clock if your hands are at 9 p.m. and 3 p.m. Now rotate those two bricks toward 1:30 p.m. and squeeze them the same way — they slide against each other more easily.)

Old faults awakened

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Oklahoma's faults are left over from pushing and pulling that occurred in North America some 300 million years ago. These faults are being awakened by oil and gas drillers who are injecting fluids into the deep underground rocks above the layers that host the faults, according to several previous studies..These fluids reduce pressure on the faults just enough for the rocks to slip apart, triggering earthquakes.

"These faults are all in rock layers that existed when the dinosaurs were around," McNamara said. "Some of them haven't been active since then, and now one of the major questions is why they are reactivating."

Oklahoma has more than 3,000 injection wells, where water left over from hydraulic fracturing, also called fracking, or from oil and gas drilling is disposed of deep underground. State officials shut down a well last week after it triggered a moderate earthquake.

However, the new study does not draw a link between oil and gas drilling and Oklahoma's earthquakes. Instead, the research team set out to locate the state's underground faults to help give experts a better idea of how large of an earthquake is possible in the state. "We're identifying faults that nobody knew about before," McNamara said.

The research is part of a massive effort to rejigger the nation's seismic hazard maps to account for man-made earthquakes. This year, for the first time, the USGS will publish hazard maps that include earthquakes caused by human activity.

McNamara said Oklahoma's potential for shaking will increase significantly in the future maps. Oklahoma's earthquake rate is now 40 times higher than it was 30 years ago. [The 10 Biggest Earthquakes in History]

"What's happening in Oklahoma, whether it's natural or induced by oil and gas, is affecting structures and homes," McNamara said. "There needs to be an assessment of building codes, and one of the major parameters [of that] is where are the active faults."

Some of the previously unknown faults threaten critical oil industry infrastructure, such as the enormous, privately owned storage facilities in Cushing, Oklahoma, the study reports. There is a fault directly underneath Cushing's airport and the oil storage facility, where 100 million barrels of oil may sit on any given day, McNamara said.

Drilling without quakes

Despite the huge escalation in Oklahoma's seismicity, some 30,000 wastewater disposal wells operate in the United States without triggering damaging earthquakes. For instance, North Dakota is the second-largest crude oil producer in the United States, but recorded only nine earthquakes between September 2008 and May 2011, according to the new Seismological Research Letters study. And the study authors attribute just one of those nine quakes to oil and gas production.

While less is known about the geology underlying North Dakota because it is so seismically quiet, the study authors suggest that local geology plays a role. The faults and regional pressure are less favorably aligned to trigger earthquakes. However, the amount of fluids injected into underground rock layers in the Dakotas could also be important, the researchers said. Oklahoma has some of the highest-volume injection wells in the country.

Editor's note: This story was updated Feb. 12 to correct the storage capacity at Cushing, Oklahoma.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus