Did Meteorite Carve Icy Antarctic Crater?

Researchers in remote East Antarctica think a massive area of fractured ice discovered last month could be a newfound meteorite impact crater.

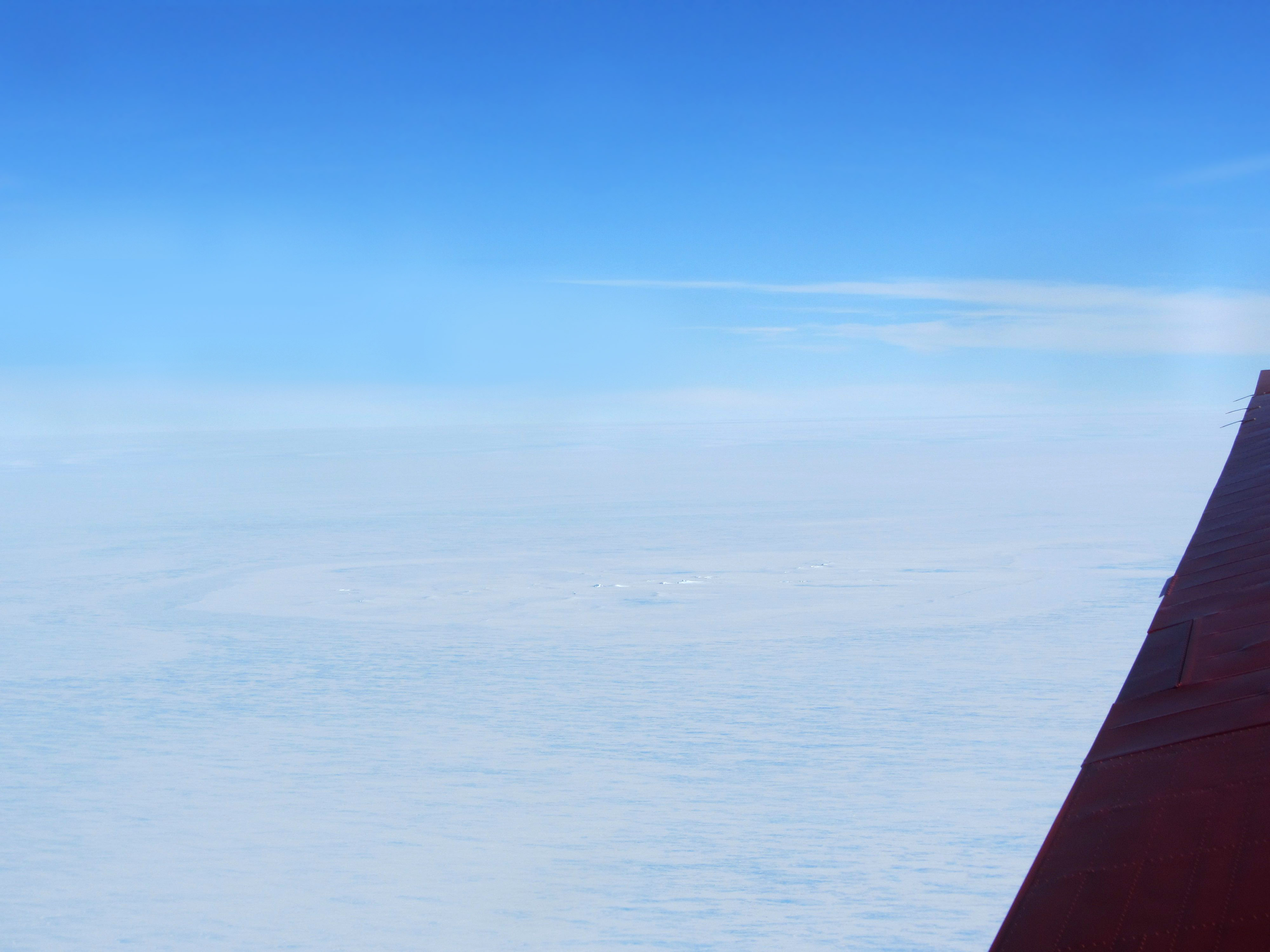

The mile-wide crater (about 2 kilometers across) is a circular scar marked by fractured, rumpled ice — a striking blot in this otherwise smooth section of Antarctica's King Baudouin Ice Shelf. It was spotted by German scientist Christian Müller during an aerial survey by plane on Dec. 20, 2014.

"I looked out of the window, and I saw an unusual structure on the surface of the ice," Müller said in a video describing the discovery. "There was some broken ice looking like icebergs, which is very unusual on a normally flat ice shelf, surrounded by a large, wing-shaped, circular structure," said Müller, a geoscientist with Fielax, a private company assisting Antarctic research. [See a video of the Antarctic crater discovery]

Lucky find

The possible impact crater is about twice the size of Arizona's Barringer Meteor Crater. Satellite images suggest the broken-up ice could be at least 25 years old.

The crater was a serendipitous find, sighted by chance north of Belgium's Princess Elisabeth Research Station. German researchers at the station intended to remotely survey the surrounding bedrock, in order to gather new details on the Gondwana supercontinent's formation and breakup between 550 million and 180 million years ago. Flying over busted-up ice shelves — the floating extensions of the Antarctic Ice Sheet — was not part of the research plan.

"We were only flying that far in the north because the radar equipment had broken, and we didn't want to waste a good flying day," said Graeme Eagles, a scientist at Germany's Alfred Wegener Institute who is currently leading the geophysical research survey. "It's been a tremendously exciting couple of weeks," he added. "It really is a very raw form of science, with a lot of people speculating on what might or might not be the cause."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At first, Müller connected the crater to a 2004 meteor blast detected above this part of East Antarctica. Recently, however, the German research team discovered the crater in satellite images dating back to 1996, Eagles said. "The [connection] to the 2004 event really piqued our interest in the first place, but I don't think what we've seen in the satellite images rules out the possibility of an impact origin," Eagles told Live Science. "It just fuzzies the story a little bit."

Extraordinary claims

If a space rock did crash-land on the ice shelf, the meteorite was likely relatively large. Indeed, the crater's sheer size warrants skepticism, experts said. [Crash! 10 Biggest Impact Craters on Earth]

As a rule of thumb, an object that formed a crater is usually about 10 to 20 times smaller than the crater itself, said Peter Brown, director of the Center for Planetary Science and Exploration at the University of Western Ontario in Canada. That means a 1.2-mile (2 km) crater would result from an object that measures roughly 325 feet (100 meters) across, Brown said.

"A very large explosion would have caused a 2-kilometer-wide crater — much larger than anything detected impacting Earth in recent history," Brown said. "So the feature seen is almost certainly not due to any meteorite impact."

Meteorite hunter Peter Jenniskens also found the crater idea implausible. "I don't think this is an impact crater," said Jenniskens, who holds dual affiliations at the SETI Institute and at NASA's Ames Research Center, both in California.

However, Eagles hinted that the German researchers have not shown all their cards. The scientists collected photos, video and data on a Dec. 26 trip to the crater site. The team mapped the ice surface in great detail with a laser-scanning instrument that records precise changes in topography. They also surveyed the area with a radar instrument that penetrates the upper surface of the ice and snow. A number of smaller circular and subcircular structures were spotted nearby on this trip. The researchers haven't yet analyzed the data, but they hope to publish their results in a scientific journal if the structure is indeed an impact crater, Eagles said.

"This thing is very unusual indeed," Eagles said. "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and in this case, as far as we can tell, is does look like it is extraordinary evidence."

Rock hunters

The researchers now must complete their Gondwana study before squeezing in any more trips to the crater, Eagles said. For instance, the team would like to eventually hunt for meteorites around the site.

Antarctica's cold, dry conditions preserve meteorites that weather away on other continents, and more than 20,000 space rocks have been discovered in targeted searches on the frozen surface.

While scientists do come to Antarctica specifically to hunt for meteorites, finding a potential impact crater was an unexpected thrill for everyone at the research station, the researchers said. "There are new and exciting things to be discovered at any moment, anytime, in Antarctica, and you don't have to send probes to land on comets to make people's eyes sparkle," Eagles said.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus