Rapid Desert Formation May Have Destroyed China's 1st Kingdom

The first known Chinese kingdom may have been destroyed when its lands rapidly transformed into deserts, possibly driving its people into the rest of China, a new study finds.

This new finding suggests that the kingdom may have been more important to Chinese civilization than experts had thought, researchers say.

Prior research suggests the earliest Chinese kingdom might have been Hongshan, established about 6,500 years ago. This was about 2,400 years before the supposed rise of the Xia Dynasty, the first dynasty in China described in ancient historical chronicles. The kingdom's name, which means "Red Mountain," comes from the name of a site in the Inner Mongolia region of China. [In Photos: Amazing Ruins of the Ancient World]

Cultural artifacts

Past excavations have uncovered Hongshan sites across northern China, including the Goddess Temple, an underground complex in the northeastern Chinese province of Liaoning known for murals painted on its walls and a clay female head with jade inlaid eyes.

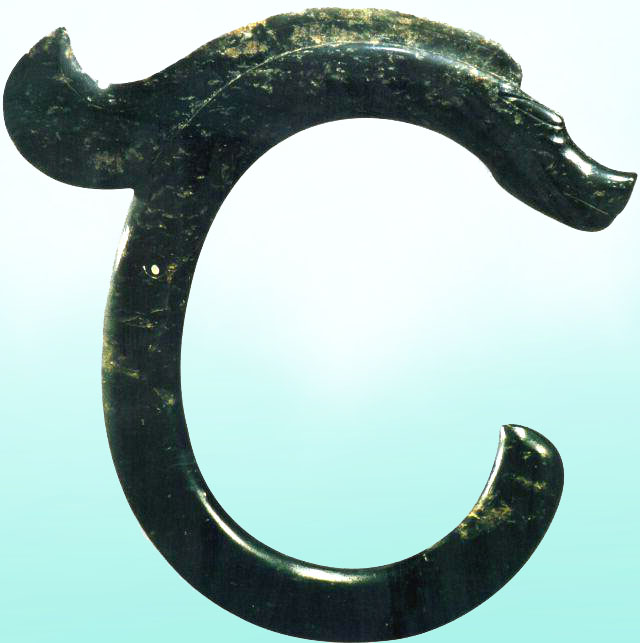

Hongshan displayed some of the earliest known examples of jade working. The first dragonlike symbol of China may have been a fishlike creature made of jade in Hongshan, researchers said.

But the importance of Hongshan to Chinese history remains a topic of debate, investigators added. The middle reaches of the Yellow River are commonly thought to be the cradle of Chinese civilization, and Hongshan was typically seen as a remote culture outside these key areas. However, the Goddess Temple, as well as remnants of sheep bones that indicate trade with Mongolian shepherds, suggest Hongshan had a complex culture.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We seem to see evidence that Hongshan was far more important to early Chinese culture than it's currently given credit for," said study co-author Louis Scuderi, a paleoclimatologist at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. "Archaeologists are having a hard time figuring out what the importance of Hongshan culture was."

To shed light on Hongshan, scientists investigated the Hunshandake Sandy Lands of Inner Mongolia, in the eastern portion of northern China's desert belt. The researchers found abundant remnants of Hongshan pottery and stone artifacts there, in an area located about 185 miles (300 kilometers) west of where the Hongshan culture was first recognized in Liaoning. The variety and large number of artifacts found in the region suggest a relatively dense population that depended on hunting and fishing, the researchers said. [The 7 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

Prior research had estimated that the deserts in northern China are about 1 million years old. However, these new findings suggest that the desert of Hunshandake is only about 4,000 years old. Lead study author Xiaoping Yang, a geologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, along with Scuderi and colleagues, detailed their findings online today (Jan. 5) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Rapid changes

The researchers analyzed environmental and landscape changes in Hunshandake over the past 10,000 years. The patterns of dunes, and depressions between those dunes, suggest that Hunshandake's terrain was once controlled by rivers and lakes.

The scientists dated the age of quartz from the area using a technique known as optically stimulated luminescence, which measures the minute amount of light that long-buried objects can emit, in order to see how long they have been buried. They found that the earliest shorelines in Hunshandake formed during the early Holocene Epoch, which began about 12,000 years ago, at the beginning of a humid period in Inner Mongolia.

Lake sediments indicated that relatively deep water existed in Hunshandake between 5,000 and 9,000 years ago. Pollen in those sediments revealed the presence of birch, spruce, fir, pine and oak trees.

"We're amazed by how much water there was back then," Scuderi said. "There were very, very large lakes, and grasslands and forests. And based on all the artifacts we've found out there, there was clearly a very large population along the lake shores."

However, the scientists found the area rapidly turned dry starting about 4,200 years ago. The scientists calculated more than 7,770 square miles (20,000 square km) in Hunshandake — a region about the size of New Jersey — transformed into desert.

The researchers suggested that water that used to flow into the area was hijacked by a river that permanently diverted water eastward, leading to rapid desertification. Hunshandake remains arid and is unlikely to revert back to wetter conditions, the researchers said.

The scientists noted that, at about the same time that Hunshandake dried out, a major climatic shift was occurring worldwide that caused extraordinary droughts on all of the continents in the Northern Hemisphere. "We think this drying happened in northern China as well, but was augmented by massive amounts of water getting diverted away from the area," Scuderi said.

This desertification likely devastated the Hongshan culture, the researchers said. It may have spurred a mass migration of northern China's early cultures into the rest of China, where they may have played formative roles in the rise of other Chinese civilizations.

"An important possible line of research in the future is to figure out how important the Hongshan culture was to the development of later Chinese culture," Scuderi said.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.