Origin of Ancient Jade Tool Baffles Scientists

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The discovery of a 3,300-year-old tool has led researchers to the rediscovery of a "lost" 20th-century manuscript and a "geochemically extraordinary" bit of earth.

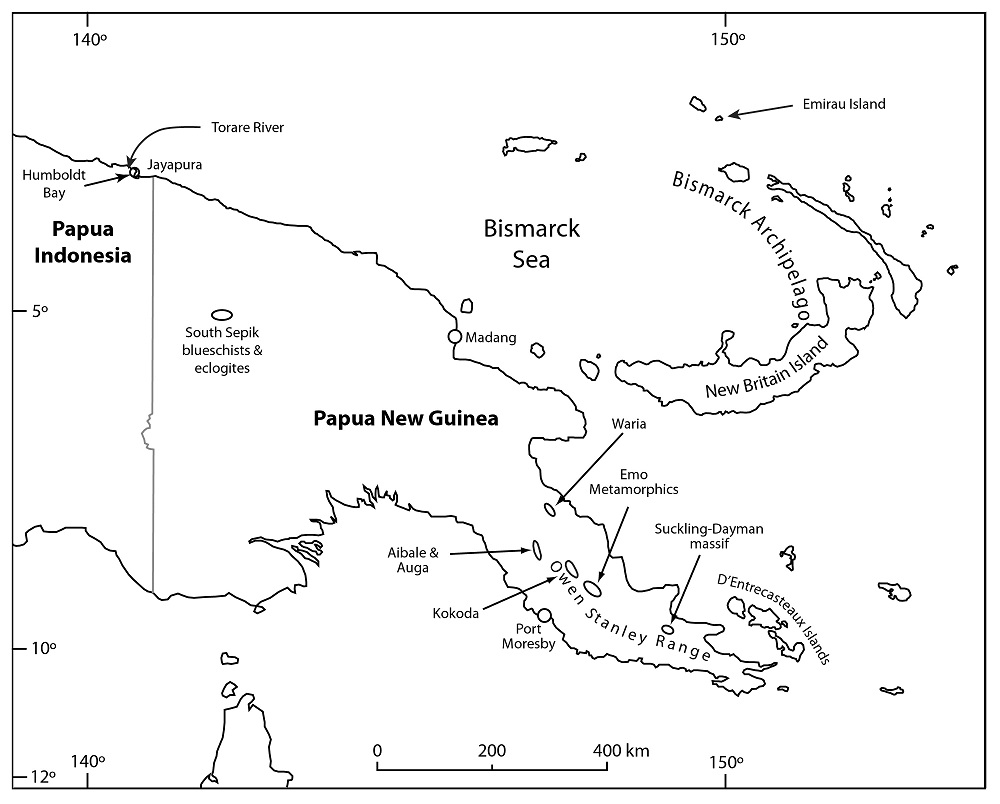

Discovered on Emirau Island in the Bismark Archipelago (a group of islands off the coast of New Guinea), the 2-inch (5-centimeters) stone tool was probably used to carve, or gouge, wood. It seems to have fallen from a stilted house, landing in a tangle of coral reef that was eventually covered over by shifting sands.

The jade gouge may have been crafted by the Lapita people, who appeared in the western Pacific around 3,300 years ago, then spread across the Pacific to Samoa over a couple hundred years, and from there formed the ancestral population of the people we know as Polynesians, according to the researchers.

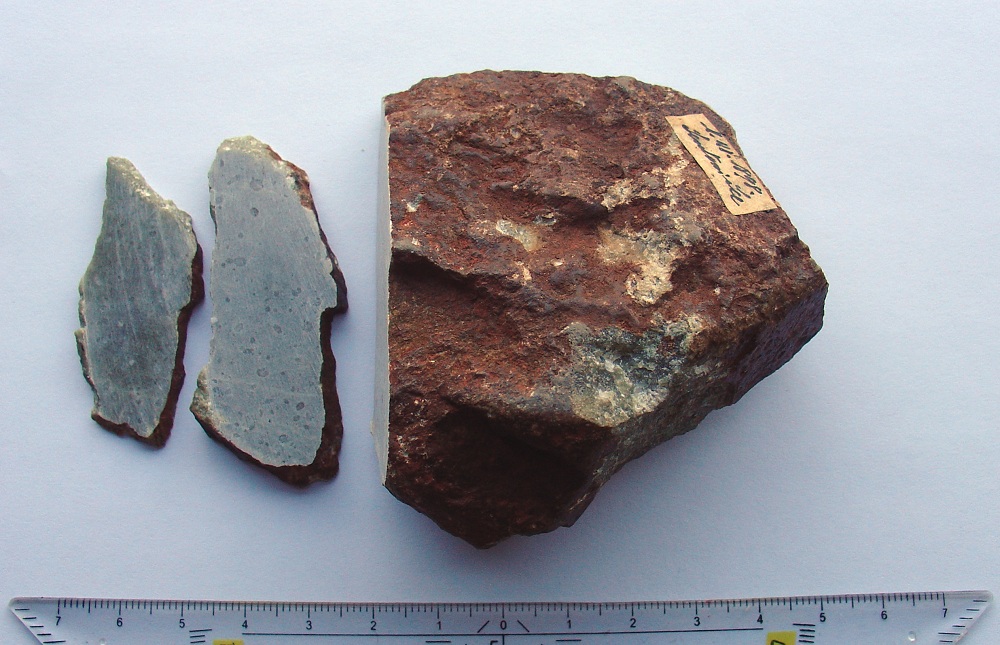

Jade gouges and axes have been found before in these areas, but what's interesting about the object is the type of jade it's made of: it seems to have come from a distant region. Perhaps these Lapita brought it from wherever they originated.

Green rocks

Jade is a general term for two types of tough rock — those made of jadeite jade and another group of nephrite jade. The stones are both greenish in color, but nephrite jade is slightly softer, while jadeite jade is scarcer, mostly found in cultures from Central America and Mexico before Europeans arrived.

"In the Pacific, jadeite jade as ancient as this artifact is only known from Japan and its usage in Korea," study researcher George Harlow, of the American Museum of Natural History in New York, said in a statement. "It's never been described in the archaeological record of New Guinea."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers from American Museum of Natural History studied the artifact with X-ray micro-diffraction, which bounces a small beam of X-rays off the specimen in order to find its atomic structure, and in turn, the minerals within the rock. A rock's mineral composition varies depending on what chemicals are in the ground when it forms. The signatures are so specific researchers can sometimes pinpoint the origin of rocks.

Surveying stone

"When we first looked at this artifact, it was very clear that it didn't match much of anything that anyone knew about jadeite jade," Harlow said. The artifact's chemical composition "makes very little sense based on how we know these rocks form."

The jadeite in the rock is different from the jadeite jades found in Japan and Korea at the time. It's missing certain elements and has more-than-expected amounts of others; the stone came from another geological source, but the researchers aren't sure where. The only chemical match the researchers knew of was a site in Baja California Sur, Mexico.

The researchers don't think it's likely that Neolithic people of thousands of years ago could have transported it across the Pacific, but they couldn't find any other explanations for its composition. That is, untilthey came across an unpublished 20th-century German manuscript.

The manuscript's author, C. E. A. Wichmann, collected some curious rocks from Indonesia in 1903 — about 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) from the site where the jade tool was found — and the chemical properties he reported seem very similar to that of the artifact. Researchers are now investigating those samples to see if modern techniques can prove that the tool came from Indonesia.

The jadeite jade source, if found, would be "something geochemically extraordinary," the authors write in the paper, to be published in an upcoming issue of the European Journal of Mineralogy.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus