Pharaoh-Branded Amulet Found at Ancient Copper Mine in Jordan

While exploring ancient copper factories in southern Jordan, a team of archaeologists picked up an Egyptian amulet that bears the name of the powerful pharaoh Sheshonq I.

The tiny artifact could attest to the fabled military campaign that Sheshonq I waged in the region nearly 3,000 years ago, researchers say.

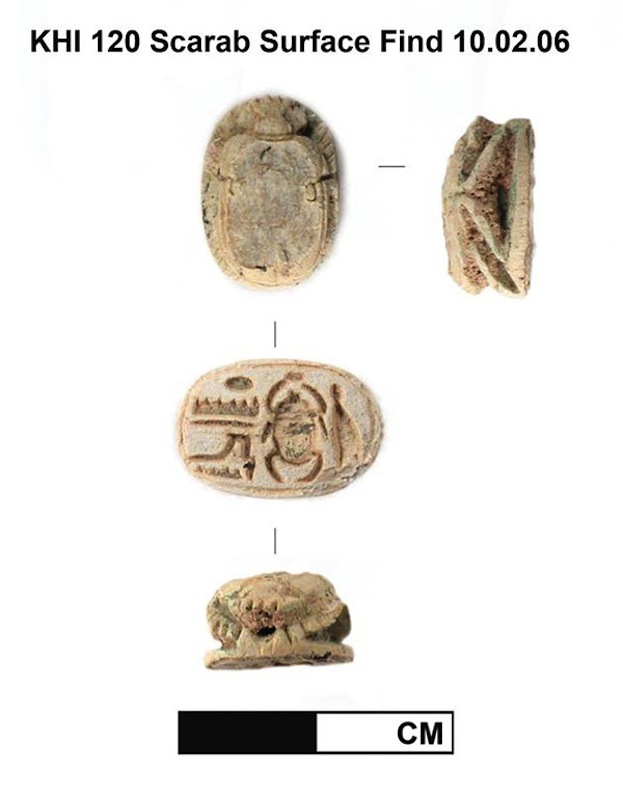

The scarab (called that because it's shaped like a scarab beetle) was found at the copper-producing site of Khirbat Hamra Ifdan in the Faynan district, some 31 miles (50 kilometers) south of the Dead Sea. The site, which was discovered during excavations in 2002, was home to intense metal production during the Early Bronze Age, between about 3000 B.C. and 2000 B.C. But there is also evidence of more recent smelting activities at Khirbat Hamra Ifdan during the Iron Age, from about 1000 B.C. to 900 B.C. [The Holy Land: 7 Amazing Archaeological Finds]

The hieroglyphic sequence on the scarab reads: "bright is the manifestation of Re, chosen of Amun/Re." That moniker corresponds to the throne name of Sheshonq I, the founding monarch of Egypt's 22nd Dynasty, who is believed to have ruled from about 945 B.C. to 924 B.C., according to a description of the artifact published online last week in the journal Antiquity.

The lead author of the paper, Thomas E. Levy, an anthropology professor at the University of California, San Diego, said the function of scarabs changed throughout Egypt's history.

"Most of the time, they were amulets, sometimes jewelry, and periodically, they were inscribed for use as personal or administrative seals," Levy said in a statement. "We think this is the case with the Sheshonq I scarab we found."

The scarab wasn't found during excavations; rather a grad student picked it up from the surface of the ground while Levy was giving a tour of the smelting slags at Khirbat Hamra Ifdan. Though the artifact was not discovered in its original archaeological context, it could provide evidence for the extent of Sheshonq I's legendary military campaign in this mineral-rich region, Levy and colleagues said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The discovery of the scarab dredges up an old controversy over the date of the southern Levant's ancient copper mines — and their ties to biblical events.

In the 1930s, American rabbi and archaeologist Nelson Glueck claimed he found King Solomon's fabled mines when he discovered copper production sites in the region. But in the years that followed, archaeologists became more wary of how much they could use biblical accounts to guide their interpretations. In the 1970s and 1980s, archaeologists who excavated in southern Jordan argued that the Iron Age did not begin there until the seventh century B.C. — much later than the 10th century B.C. reign of King Solomon.

However, in a 2008 study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Levy and colleagues used radiocarbon dating to show that artifacts at Khirbat en-Nahas — another ancient copper mining and smelting site in the Faynan that's so huge it can be seen from space — were actually as old as the 10th century B.C.

"In my opinion, the debate over dating copper production in the Faynan region is over," Levy told Live Science in an email. "We produced over 130 high-precision radiocarbon dates for the main production sites and a range of other data. As for Solomon, without inscriptions, we still don't know who controlled the copper production at this time for sure."

But now, they apparenly have inscriptions linking the region to Sheshonq I. In the 2008 study, Levy and colleagues had identified a major disruption in industrial copper production in Faynan during the 10th century B.C., which they attributed to Sheshonq I's military campaign.

The Hebrew Bible references the exploits of the Egyptian king "Shishak" — thought to be Sheshonq I. The Egyptian king was said to have invaded the region five years after King Solomon's death in 931 B.C., conquering cities in Jezreel Valley and the Negev area and even marching on Jerusalem. Inscriptions at the Karnak temple complex in the ancient Egyptian city of Thebes also brag about Sheshonq I's military campaign in the region.

Levy and colleagues previously found scarabs in Khirbat en-Nahas that resembled popular amulets from Sheshonq I's reign. But the new scarab contains the first written evidence the researchers have to link the disruption to the pharaoh's forces, Levy said.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.