Should You Take Daily Aspirin to Prevent Cancer?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

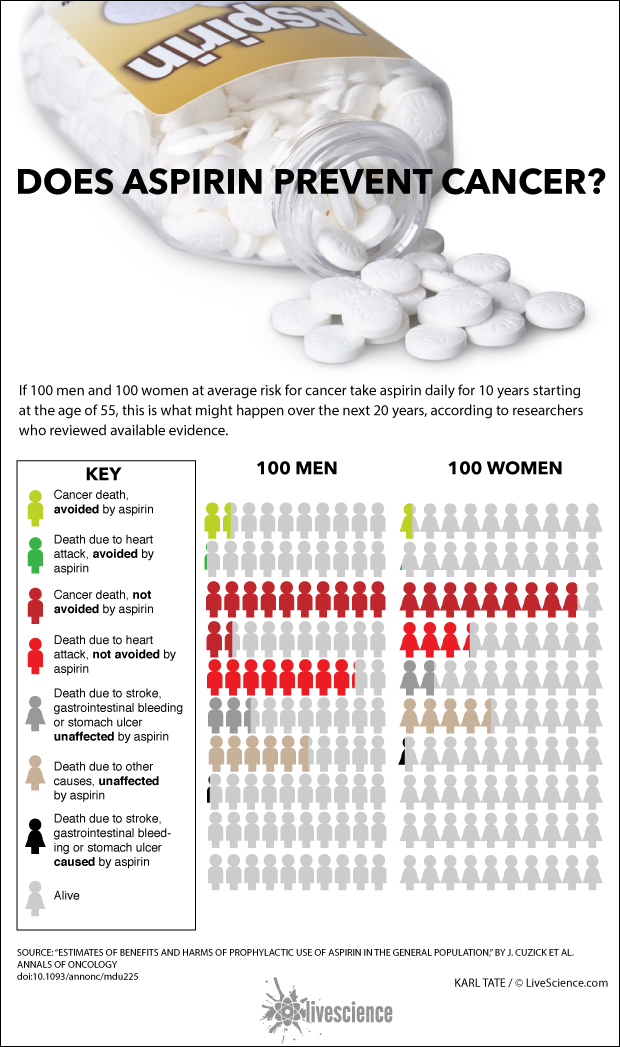

The potential benefits of taking a daily dose of aspirin for cancer prevention may outweigh the risks, a new review of studies suggests. However, doctors are divided on whether these findings mean that everyone should start taking an aspirin every day.

The researchers reviewed previous studies that had investigated whether there was a link between aspirin and cancer prevention. The results of the studies varied depending on the site of the cancer and the age of people who took daily aspirin, among other factors. But overall, the researchers estimated that if everyone between ages 50 and 65 started taking aspirin daily for at least 10 years, there would be a 9 percent reduction in the number of cancers, strokes and heart attacks in men, and about a 7 percent reduction of cases in these health conditions in women.

The researchers also found that overall, the number of deaths from all causesover a 20-year period would be reduced by 4 percent.

Most of the beneficial effects linked to aspirin use were seen in people with colon, stomach and esophageal cancers, the researchers said.

To put the findings into perspective, the results mean that if 100 women started taking daily aspirin at age 50 and continued for 10 years, there would be one fewer case of cancer, stroke or heart attack than expected. The benefits appear larger for men — if 100 men started taking daily aspirin at age 65, the group would have about 4 fewer cases of those conditions than expected, the researchers found. [Infographic: How Taking Aspirin Affects Death Rates]

The harms of regularly taking aspirin included a higher risk of bleeding in the stomach and other parts of the digestive tract, and a less common type of stroke caused by bleeding of vessels in the brain. But the increase in risk was modest, and overall, the researchers found that the rates of serious or deadly bleeding were low for people younger than age 70 but increased sharply after that age.

"Whilst there are some serious side effects that can't be ignored, taking aspirin daily looks to be the most important thing we can do to reduce cancer after stopping smoking and reducing obesity, and will probably be much easier to implement," study researcher Jack Cuzick, head of the Centre for Cancer Prevention at Queen Mary University of London, said in a statement. Cuzick, who is also on the advisory board of Bayer — the maker and trademark holder of aspirin — added that people should consult with their doctor about the possible risks before beginning daily medication.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

More research is needed to know who will benefit most from taking aspirin and who is most at risk of side effects, the researchers said. The study was published today (Aug. 5) in the journal Annals of Oncology, and was funded by several associations, including the American Cancer Society, the British Heart Foundation and Cancer Research UK.

Should you take aspirin for cancer prevention?

The most promising evidence of aspirin's benefits comes from studies on colon cancer and stomach cancer. But it is not clear how much of the risk reduction is actually due to aspirin itself. It may be that aspirin helps spot such cancers earlier, rather than preventing disease, said Dr. David Bernstein, a gastroenterologist at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, New York, who wasn't involved in the new study.

It may be that people who take aspirin regularly are more likely to experience bleeding and, therefore, visit a doctor because they noticed blood in their stool. Then, during the investigation for the source of the bleeding, if the patient has any precancerous polyps or even cancer, it gets detected earlier, when it has the best chance for treatment, Bernstein said. If people got screened for colon cancer as they are advised to, there would probably be higher rates of cancer reduction, he said.

"Aspirin shouldn't be given for the purpose of preventing cancer," Bernstein said. "It should be given for whatever medical indication is required — for example, if someone has heart disease."

However, Dr. Omar Kayaleh, the medical oncology team leader for the gastrointestinal cancers section at UF Health Cancer Center in Orlando, said that even if aspirin reduces cancers by increasing early detection, that's only part of the picture, and studies have suggested that people on aspirin actually develop fewer polyps.

The data on benefits of aspirin for colon, esophagus and stomach cancer is strong enough to recommend the drug, especially to people who already have these cancers or if they have family members with these cancers and thus may be at higher risk for developing them, Kayaleh said.

In the new study, researchers estimated that using aspirin reduces colon cancer risk by about 30 percent. Considering that colon cancer is a common cancer in the United States, with about 130,000 new cases each year, this risk reduction would translate to a substantial number of people, Kayaleh said.

"I take an aspirin a day, just based on this information," Kayaleh said.

As far as the potential benefits for heart attack prevention, many medical associations recommend aspirin only for people at risk. For example, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) says that daily aspirin is worth considering for people who have had a heart attack or stroke, but the agency maintains that the data do not support the use of aspirin as a preventive medication for healthy people. Similarly, the American Heart Association recommends the use of aspirin in people whose risk for heart disease or stroke is sufficiently high for the benefits to outweigh the risks.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus