How the Ebola Outbreak Became Deadliest in History

The reasons why the Ebola outbreak in West Africa has grown so large, and why it is happening now, may have to do with the travel patterns of bats across Africa and recent weather patterns in the region, as well as other factors, according to a researcher who worked in the region.

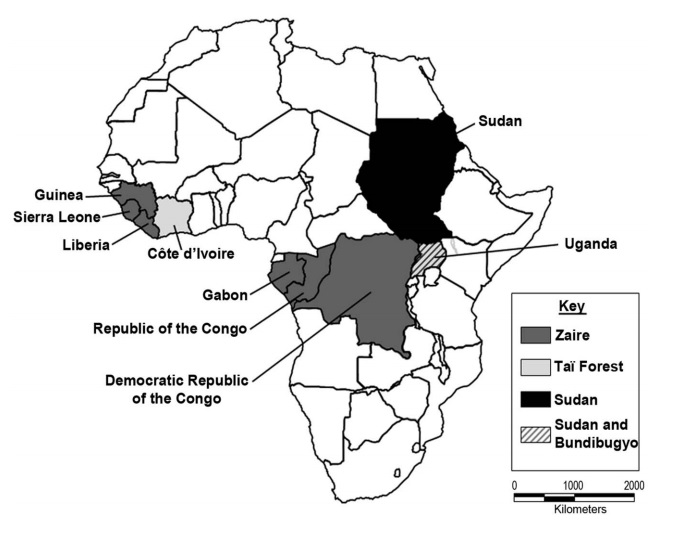

The outbreak began with Ebola cases that surfaced in Guinea, and subsequently spread to the neighboring countries of Liberia and Sierra Leone. Until now, none of these three West African countries had ever experienced an Ebola outbreak, let alone cases involving a type of Ebola virus that had been found only in faraway Central Africa.

But despite the image of Ebola as a virus that mysteriously and randomly emerges from the forest, the sites of the cases are far from random, said Daniel Bausch, a tropical medicine researcher at Tulane University who just returned from Guinea and Sierra Leone, where he had worked as part of the outbreak response team.

"A very dangerous virus got into a place in the world that is the least prepared to deal with it," Bausch told Live Science. [Ebola Virus: 5 Things You Should Know]

In a new article published today (July 31) in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, Bausch and a colleague reviewed the factors that potentially turned the current outbreak into the largest and deadliest Ebola outbreak in history. Although the focus is now on getting the outbreak under control, for long-term prevention, underlying factors need to be addressed, they said.

Here are five potential reasons why this outbreak is so severe:

The virus causing this outbreak is the deadliest type of Ebola virus.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Ebola virus has five species, and each species has caused outbreaks in different regions. Experts were surprised to see that instead of the Taï Forest Ebola virus, which is found near Guinea, it was the Zaire Ebola virus that is the culprit in the current outbreak. This virus was previously found only in three countries in Central Africa: the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo and Gabon.

Zaire Ebola virus is the deadliest type of Ebola virus — in previous outbreaks it has killed up to 90 percent of those it infected.

But how did the Zaire Ebola virus get to Guinea? Few people travel between those two regions, and Guéckédou, the remote epicenter of first cases of disease, is far off the beaten path, Bausch said. "If Ebola virus was introduced into Guinea from afar, the more likely traveler was a bat," he said.

It is also possible that the virus was actually in West Africa before the current outbreak, circulating in bats — and perhaps even infected people but so sporadically that it was never recognized, Bausch said. Some preliminary analysis of blood samples collected from patients with other diseases before the outbreak suggests people in this region were exposed to Ebola previously, but more research is needed to know for sure.

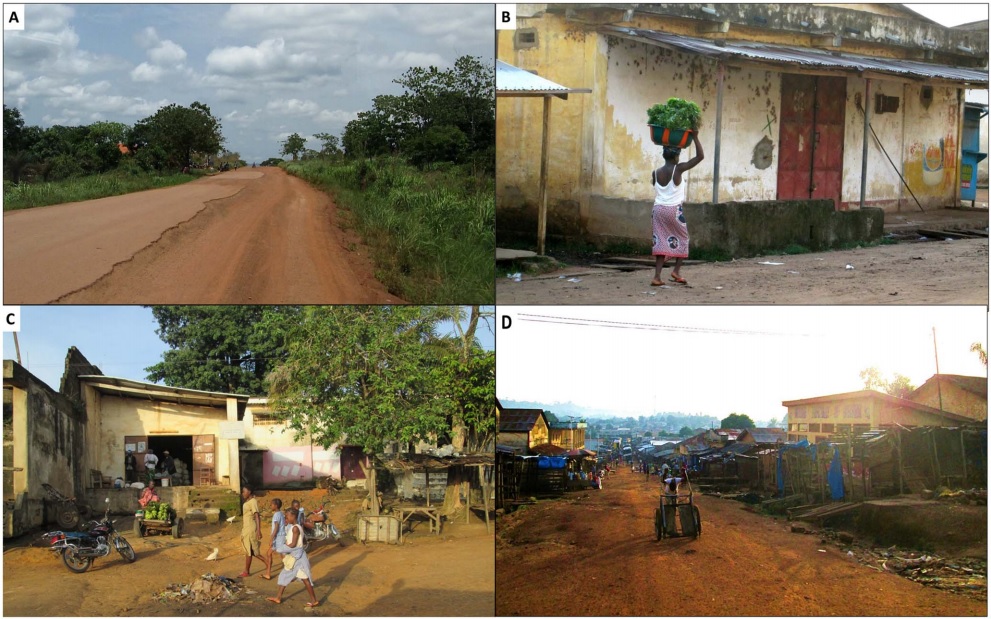

The affected countries are among the poorest in the world.

Guinea is not the only place bats migrate to, but it is one of the poorest countries in the world, ranking 178 out of 187 countries on the United Nations' Human Development Index. More than half of Guineans live below the national poverty line, and about 20 percent live in extreme poverty. Similarly, Liberia and Sierra Leone rank 174th and 177th on the Human Development Index. "These are countries coming out of civil war and struggling to get back on their feet," Bausch said. They are poorly equipped to respond to an outbreak and lack coordination to monitor people's movements across regions.

"Biological and ecological factors may drive emergence of the virus from the forest, but clearly, the sociopolitical landscape dictates where it goes from there — an isolated case or two, or a large and sustained outbreak," he said.

These countries lack robust health care systems.

A poor economy results in weak health care systems that are not prepared to respond to an outbreak and lack even basic health resources. It is not at all uncommon for the hospitals in the region to not have protective gloves, masks, clean needles and disinfectants, Bausch said.

Being unprepared to contain an infectious disease may even turn the health care setting into a hub for further spread of the disease, he said.

Poverty pushes people farther into the forests.

Even if the Ebola virus had been circulating in Guinea for some time, animals carrying the virus or other pathogens are not usually in the vicinity of humans, but rather deep in the forests with little chance of coming into contact with people. However, impoverished people tend to move into such territory in search of resources. [10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species]

"Poverty drives people to expand their range of activities to stay alive, plunging deeper into the forest to expand the geographic as well as species range of hunted game, and to find wood to make charcoal and deeper into mines to extract minerals," Bausch said. This increases people's risk of exposure to Ebola virus in remote corners of the forest, he added.

An extremely dry season may have triggered the Ebola to break out.

The first case of Ebola was identified in Guinea in December 2013, at the beginning of the dry season. In other countries, too, outbreaks often begin during the transition from the rainy to dry seasons, when conditions become drier sharply, Bausch said. It is possible that drier conditions somehow influence the number or proportion of bats infected with the Ebola virus, or the frequency of human contact with them.

More in-depth analysis is needed to better understand the weather conditions this year in Guinea, but "inhabitants in the region do, indeed, anecdotally report an exceptionally arid and prolonged dry season," Bausch said. This may be due, in part, to the extreme deforestation in the area over recent decades, he said.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.