Doc X-Rays His Broken Headphones to Fix Them

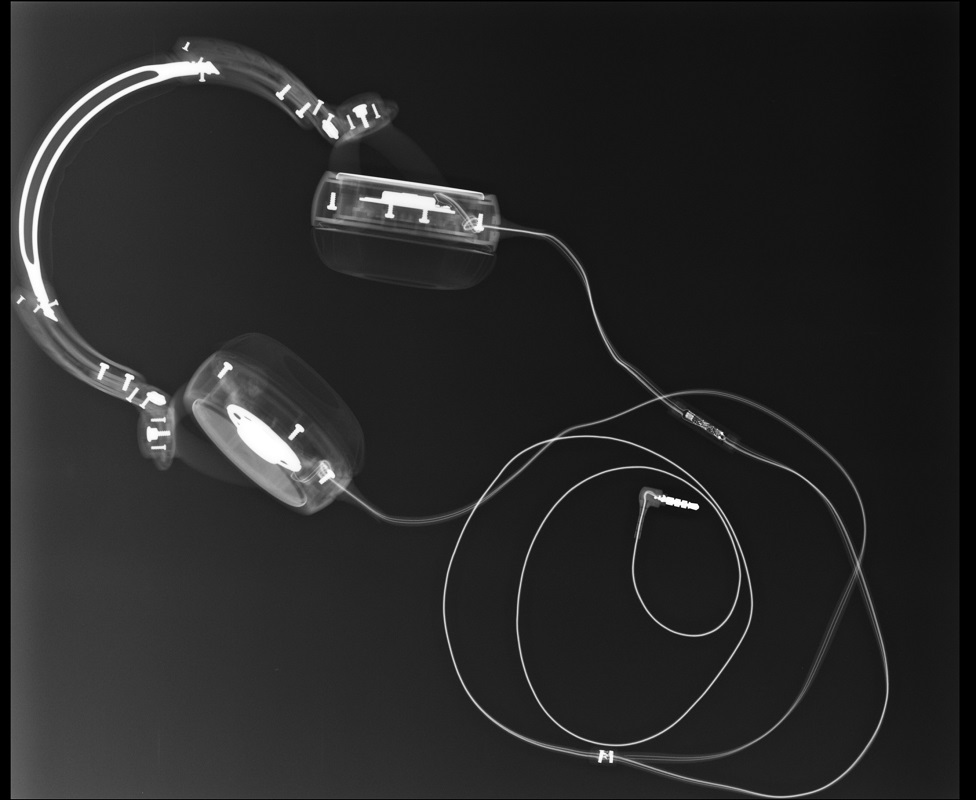

When faced with a pair of broken headphones, a doctor in California used his medical expertise to diagnose the problem and avoid buying a new set: He X-rayed the headphones and found a tiny break in the cords. Dr. Matt Skalski, a radiology resident at Southern California University of Health Sciences, said he damaged his headphones when vacuuming his office.

"My headphones were sitting on my desk and the cords were dangling down. They got sucked into the vacuum all the way up to the headphones," Skalski said. "I pulled both the cords and got them out of there, and it looked like there was no damage." But when Skalski tried to use the headphones the next day, the right earphone wasn't working at all. "The only place I could access the anatomy of the headphone was the earmuff, so I pulled off the earmuff and unscrewed it, and looked inside. It seemed undamaged. So I thought the problem must be in the cord."

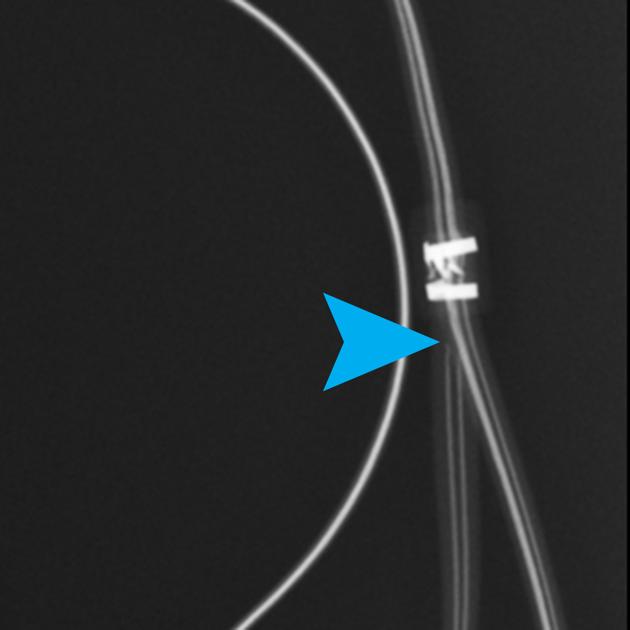

So Skalski turned to another resource at his disposal, the X-ray machine. He X-rayed different parts of the cords, searching for a defect in them, zooming in and out until he found a 4-millimeter tear in the wires, right next to the splitter. "So I just spliced it out and put it all back together and they are now as good as new," Skalski told Live Science. [See the X-ray scans]

Skalski reported his case of the headphone in Radiopaedia.org, a Wikipedia-type forum for radiologists and medical students, where actual medical case reports (of human patients) are presented and discussed.

"Closed fracture of a speaker wire within its rubber/plastic sleeve is a rare headphone injury, usually due to a traction trauma," Skalski wrote in his report of the case. [16 Oddest Medical Case Reports]

Skalski also included "intraoperative" and "postoperative" photos of the surgery on the headphones, in which he repaired the defect by reattaching the torn wires.

"The headphones showed 90 percent recovery, with only mild volume loss overall, and approximately 4 centimeters of cord shortening," Skalski wrote in the case report.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The surgery cost Skalski about $1 and 30 minutes of his time, he said, a far better option than having to buy a new set of headphones for about $200. As for the expense of taking an X-ray, most of the cost is actually due to the initial setup of the equipment and payments to the hospital and radiologists, he said. The cost of firing the machine once is negligible.

The headphone set is not the first object Skalski has X-rayed. Sometimes, for educational purposes, Skalski and his colleagues take X-ray images of random objects for medical students to identify, in what they call "the challenge of the unknown." For example, they once X-rayed a bonsai tree.

Although it may seem like a silly aside to image a common household object —such as headphones — to determine what is wrong, it illustrates the value of imaging in diagnosing problems, Skalski said. The case of the headphones also mimics the process doctors go through when treating patients, he said.

"Many things have to come together in the right order to take something that isn’t working, whether it be a human part or object part, and follow it through to arrive at a positive outcome," Skalski said.

For example, the problem first has to be localized to a certain area, then tests have to be done to find the correct diagnosis, and these tests often include medical imaging, Skalski said.

"I had initially looked through the length of the headphone cord, just to be frustrated to find it completely intact. … Before I lost hope though, it occurred to me that I should dramatically zoom in on the 'joints' of the wire on each image to asses for a miniscule defect as the culprit, as these sites are biomechanically more vulnerable than the rest of the cord," Skalski said.

"This intuition, as is observed in daily practice with real patients, can be the difference between making and missing a critical diagnosis," he said.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus